Each year the Melbourne International Film Festival helps finance feature length narrative and documentary films through an initiative called the MIFF Premiere Fund. With his updated remake of Richard Franklin’s 1978 horror flick, Patrick, director and Ozploitation expert Mark Hartley returns to MIFF with his third Premiere-Funded feature film.

Inspired by the central concept of the original, Hartley retells the story of a young comatose man with telekinetic powers who develops a unique relationship with his nurse. Free from the rampant sexism and exploitation of the original, Hartley’s Patrick is a successful, and surprisingly feminist, update. Keyframe talked to Mark Hartley about his transformation of the “bug-eyed freak.”

Keyframe: After Not Quite Hollywood and Machete Maidens Unleashed I think audiences have really been expecting to see another documentary on exploitation films from you, namely, Electric Boogaloo: The Wild Untold Story of Cannon Films, which I believe is still currently in the works. What made you choose to remake Patrick and is Electric Boogaloo still in the making?

Mark Hartley: It’s very kind of strange how my career’s turned out because I never ever thought of myself, or wanted to be, a documentary filmmaker. I never had any inclination of even making a documentary and then, the story of Not Quite Hollywood is such a great story, and it was a story that no one else is going to tell, so I figured I should. And all the while, prior to that and while we were making—trying to get Not Quite Hollywood financed—I was still making narrative features, which is what I always, always wanted to do. My background was music videos and I spent a long time making music videos and ads and that was a stepping-stone to narrative features. And I never thought in my wildest dreams ever documentaries would be the stepping-stone to narrative features, so, yeah, that’s how it happened.

I was a gun for hire on the shoot of Machete Maidens—it wasn’t a documentary that I instigated at all and it was really just to pay the bills while we were developing Patrick—and Electric Boogaloo was just a stopgap thing because once we got Patrick financed we had an eight month period where we had to wait for actors to become available, and I thought I might as well make another documentary at that point. I thought it’d be great to make one about iconic eighties genre films, and that Cannon seemed to be just an amazing story there, so that’s where that fitted in. And subsequently, with Patrick getting financed and made, suddenly Electric Boogaloo got financed and I’ve discovered I’ve got to make another documentary next year, so it’s been a very kind of strange, diverse, career path, without any real planning.

Keyframe: Do you want to make more feature films though, is that what you’re still hoping to move into next?

Hartley: Yeah, that’s always been—I won’t say the plan, I’ll say the dream—but yeah, I hope we can follow Patrick up with a lot more narrative feature films.

Keyframe: I’ve read that you don’t think that every film should be remade but that remaking Patrick was something that was really close to your heart; you had said that Richard Franklin was a childhood hero, you both attended the same high school. Obviously you’ve also got influences of a working relationship with Anthony I. Ginnane, and the writer, Justin King, who worked with you as a researcher on Not Quite Hollywood. How did the idea for making Patrick come about?

Hartley: We were just looking for any chance to make a feature film to tell you the truth. Justin and I had written quite a few scripts that had had come close to getting up but hadn’t. And at one point we just had a conversation with Tony and said, ‘You know, Patrick would be a great idea for a remake.’ And he said, ‘It’s surprising you say that, because I’ve been thinking about that’, and he had other writers from the U.S. writing treatments prior to us talking to him about it. And so we wrote a treatment and we got draft funding and he went away and made it happen.

At one point I did sit down with Justin and we were talking about all the remakes overseas, and I said, you know, out of all the films in Not Quite Hollywood, what do we think would be the—it wasn’t even plan to remake them ourselves, it was just a plan to think what would work best as [a] remake now—we thought it would be Razorback and Patrick; Patrick because the idea was so great and Razorback because the technology improved so much.

And Tony was very open to the idea; he really liked our take on it. The other treatments he’d had from overseas’ writers had all basically turned Patrick into Freddy Krueger just killing people willy nilly with his psychic powers and we wanted to do something very different to that.

Keyframe: It is really different and the Patrick character himself is really different; there’s this concept the original character is such a ‘bug-eyed freak,’ that’s how he’s described, that’s how you read about him—

Hartley: That’s how I like to describe him, [laughs] and with Robert Thompson so far away he’ll never read about it.

Keyframe: True. Jackson Gallagher is a really young, good looking character. Was this a conscious decision to cast someone more traditionally good looking onscreen because his character’s comatose and the audience gets very little chance to identify with this character? Did you want to elicit more empathy from the audience?

Hartley: I’m not sure it’s about the audience’s connection with Patrick; I think it’s more about Kathy’s connection with Patrick. I never could quite understand in the original why Kathy was so drawn to the bug-eyed freak, to tell you the truth. And here we thought there needs to someone she can instantly feel sorry for and want to nurture but also have some kind of, you know, romantic yearning for. And it seemed the best way to do that was to have someone who looked beautiful.

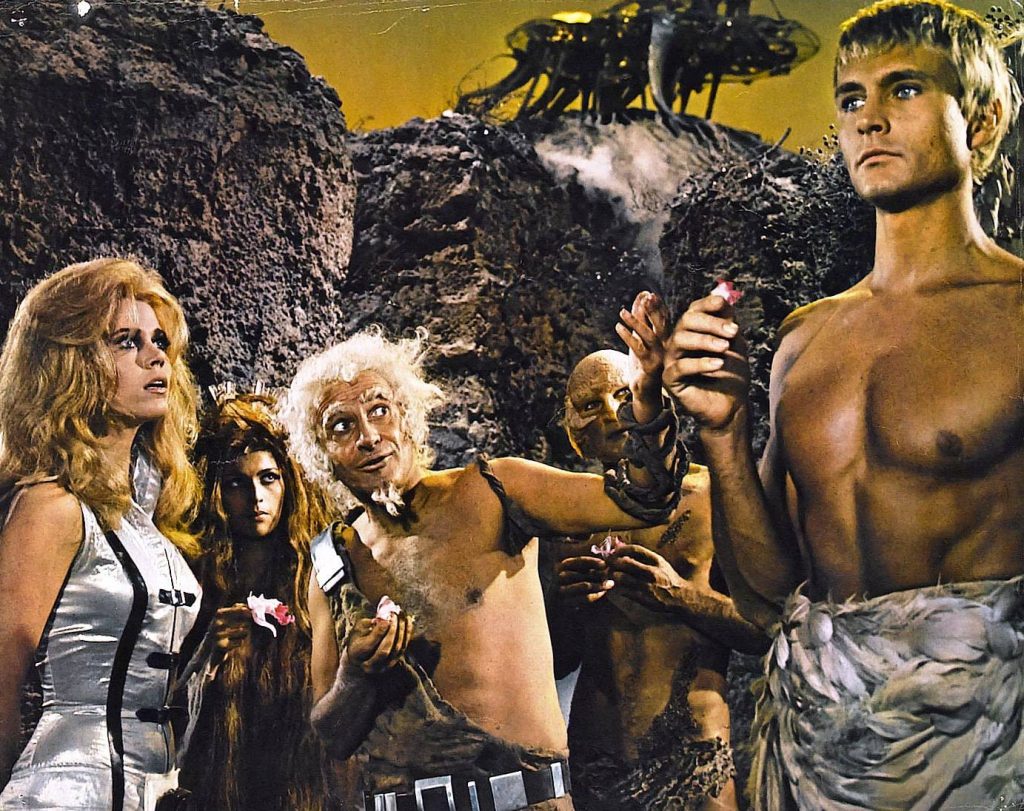

We always thought of our Patrick as like John Phillip Law in Barbarella, Pygar the Angel who was just so beautiful, who was so pristine and so angelic. I think they say in it he was described as a wax effigy more than a person in the script. That’s kind of how we wanted to go. … He brings a little bit more to that. Not only will particular women find him good looking, but there’s something there behind the eyes that’s a little bit kind of off and disturbing. And he was such a lovely guy, so that helped too.

Keyframe: I want to talk as well about Sharni Vinson. Particularly because there’s another film in the Night Shift program at MIFF this year, You’re Next, starring Sharni.

Hartley: Which I have to admit I’m yet to see.

Keyframe: Right. I had wondered if you’d seen it yet. There’s a real connection.

Hartley: Trust me, I was so desperate to see it because—oh, I’ll tell you the truth and Sharni won’t mind me telling you this—I never… it was heavily suggested to us that we cast Sharni after You’re Next had been so well received in Toronto. And so I really didn’t have a lot to do with it. So all I’d seen Sharni in was Step Up 3D, Blue Crush 2, and basically, you know, literally just before we made Patrick, Bait 3D came out. So I wasn’t actually filled with a lot of confidence that here was a girl that could embrace genre. But all I had to go on was amazing reviews of her in You’re Next.

Keyframe: Yeah, you definitely should see it, there’s a really wonderful connection I think between her role in that and her role in your film, and she’s really becoming the Australian poster girl for new horror’s Feminist Final Girl, I think.

Hartley: She just has to be an action chick. Every time I read anything with her, any time she would open her mouth on set, she wants to be the new Lara Croft. Because, you know, of her dancer background.

Keyframe: Yeah, well she brings a real physicality to the role! She doesn’t feel like a sexualized object at any time and I feel like this is really different from the original Patrick as well. In your film, even when she’s getting out the shower, you know, in a towel, and despite being a film about desire, despite her being the object of Patrick’s desire, it really doesn’t feel like she’s objectified or sexualized at any time in the film.

Hartley: I didn’t want anyone to feel like that… Justin King describes our film as ‘a smart dumb horror film,’ in a way. Because we really wanted to make something slightly more prestige than obviously what the film is—in a way. And you know I didn’t want—even though it has exploitation elements, and the last third of the film really does ramp up with a lot of, well, it’s not gore, I don’t know what it is, maybe it’s a slightly more extreme content than the previous two-thirds of the film—I never wanted anything to do with Patrick’s mother to seem sexualized at all either, the nudity. I wanted that to be confronting more than anything titillating. And the same with Sharni. I mean, apart from the one kind of very, very brief sex scene with Sharni where you assume that she’s having sex with Wright [Martin Crewes], that was the only kind of thing even remotely in the film that I thought should be at all titillating. And that quickly turns into something that is un-titillating.

Keyframe: Yeah it does.

Hartley: I guess, I mean, in terms of other horror films, which are all about titillation and exploitation of women, we didn’t want this film to be like that. We tried to write the characters for [the] women, and Charles Dance as well, to be as strong as possible so that we could attract good actors for them. And Sharni was great because from day one she really gave it her all. The first thing we shot with her was her trying to get Ed out of the cool room.

Keyframe: Right. Wow.

Hartley: And so from that day on I thought, okay, well I’m not in trouble.

Keyframe: This is your third MIFF premiere funded film too, is it easier the third time to get funding, would you still have been able to make this film and would you still tried to have made this film if you didn’t get that funding?

Hartley: Without the MIFF premiere fund? Look, Tony, was amazing. Tony Ginnane was amazing in the fact that he was relentless in his pursuit of finance. Every avenue he explored and he got the film up. And he got the film up with first time narrative director in myself, first time cinematographer, first time writer; I mean that’s really difficult to do that. And so look I can’t say whether he would have found alternate funds if MIFF didn’t give us any money, but I’m sure he would have spent a lot of time trying, [laughs], and no, I mean MIFF have been very, very kind to me and they’ve got money in Electric Boogaloo as well. It’s great for them that the premiere went down so well, and that the film is finding an audience at MIFF and let’s hope that it continues to find an audience outside of MIFF when it gets a theatrical release.

It’s very difficult with this film trying to put our finger on what exactly the key demographic is for it as well. It isn’t Saw, it isn’t Wolf Creek, it isn’t the horror films that people are accustomed to. So it’s very hard to sell it as a horror film, and like you said, there is a really strong female lean towards it once they see the film; it’s just getting them in the cinema to see it.