Conrad Hall is a legendary cinematographer whose work on Cool Hand Luke and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid can be credited with creating the sun-dappled aesthetic of 1970s American New Wave cinema: The gritty, sweaty faces of anti-heroes bucking the establishment, set against the landscape of untamed American vistas; a neo-western mythos for a dying Hollywood system. Without Hall, there may have been no Easy Rider. And, ironically, if there had been no Easy Rider, Hall may not have been afforded the opportunity to help create the ultimate authoritarian counterpoint to the counterculture: A fascist cop film called Electra Glide in Blue.

In Electra Glide in Blue, a leather-clad motorcycle cop named Big John (an ideal role for the diminutive Robert Blake) plays it by the books in a rural Arizona speed trap, while his colleagues constantly flaunt their power over wise-ass hippies. John is vying for a job as a homicide detective when he stumbles upon a suicide that he believes is a murder. But when he’s tasked with assisting hot-shot Detective, Harve Poole, John soon finds that detectives are just as crooked as traffic cops. A hippie called Zemko (played by Peter Cetera, the lead singer of Chicago) is arrested on the trumped up murder charge. John continues to investigate—even after he is demoted back to his old beat for unwittingly sleeping with Harve’s girlfriend—and finds the real killer. John confronts a fellow officer (and friend of his) about his involvement, leading to a fatal shoot-out. In the stunning final scene, John gives some hippies a fortuitous break which unfolds as a mirror image of the ending of Easy Rider.

This was the first and only directing credit for music producer James William Guercio (who worked with acts such as Chicago, Frank Zappa, and the Beach Boys), but he was savvy enough to secure recent Oscar-winner Conrad Hall to serve as DP for the project. Electra has Hall’s fingerprints all over it: Old men drinking in smoky bars. Off-camera dialogue over meandering detail shots. Lonely, aging leading ladies with complex inner lives. Although Hall is primarily remembered for his work on male-centric films, one of the most heartbreaking scenes in Electra is when John and Harve meet up with Jolene (full-time bartender and part-time girlfriend to the two men) late one night at her bar. Jolene is drunk, disillusioned, and ready to “spill the tea” about how each man ranks in the bedroom. Her cringeworthy confessions leave Harve nearly comatose in his “White Despair”—and the fact that the actress who played Jolene (Jeannine Riley) had previously worked on all-American TV shows, like Petticoat Junction, makes her performance all the more biting.

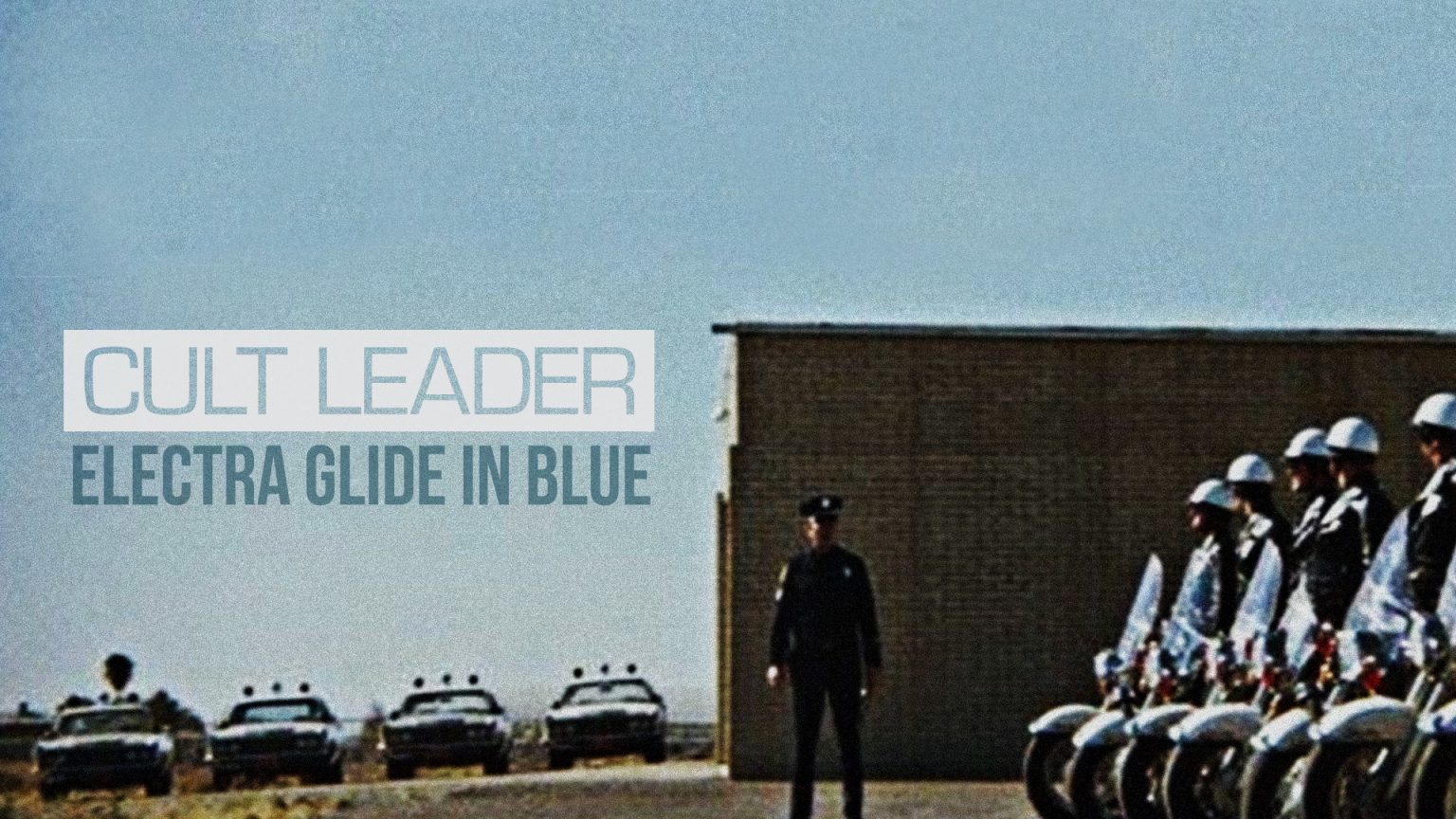

While Hall created memorable visuals, Guercio’s soundtrack added a considerable amount to the mood of the film. In one of the most notable scenes, “Most of All” by The Marcels plays over shots of John dreamily getting dressed for his first homicide case—Stetson hat, cowboy boots, cigar, no pants. The coupling of ersatz Americana and romanticized masculinity provides a possible point of origin for every subsequent scene of this type from Lynch, Tarantino, Jarmusch, and Wes Anderson. Anachronistic music was rarely used to such effect in movies of this time. Although Martin Scorsese‘s Mean Streets—also released in 1973—is usually lauded for starting the trend, Guercio deserves credit for helping to create one of modern cinema’s most ubiquitous tropes. However, the ultimate juxtaposition of sentimental music over fascist biker imagery actually predates Electra Glide in Blue by a decade. In 1963, Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising placed shots of gay Nazi bikers over romantic music of the era, like Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet.” Many of the motifs of Electra harken back to Scorpio Rising (machismo, motorcycles, black leather, and fascism), which Hall emphasizes with Leni Reifenstahl-style shots of militarized police authority.

By virtue of not being the most autocratic traffic cop in his precinct, Big John acts as the audience’s surrogate. He is a man with a code and we see him doling out “justice” with equal measure to fellow Vietnam vets, hippies, and his superiors. One of the reasons Electra Glide in Blue never gained traction after its Palme d’Or nomination at the Cannes Film Festival may be because of its apparent ambivalence. It was too sympathetic to the counterculture for conservatives and too sympathetic to cops for liberals, and it wasn’t campy or exploitative enough to fall somewhere in between. This moment may seem like a less than ideal time to ask for consideration of a film about white cops, but Hall and Guercio deserve credit for shining a light on an issue that took many individuals an extra forty years to figure out.