It would hardly be controversial to say that the Mission: Impossible films form a franchise. The films were conceived with sequels in mind—there are four so far, with the fifth hitting theaters this weekend. These movies are the embodiment of franchise filmmaking, which tries to reach the widest possible audience in order to recuperate production costs. To that end, these films tend to lean into what has worked in the past in order to ensure that the whole money-making operation keeps on running indefinitely.

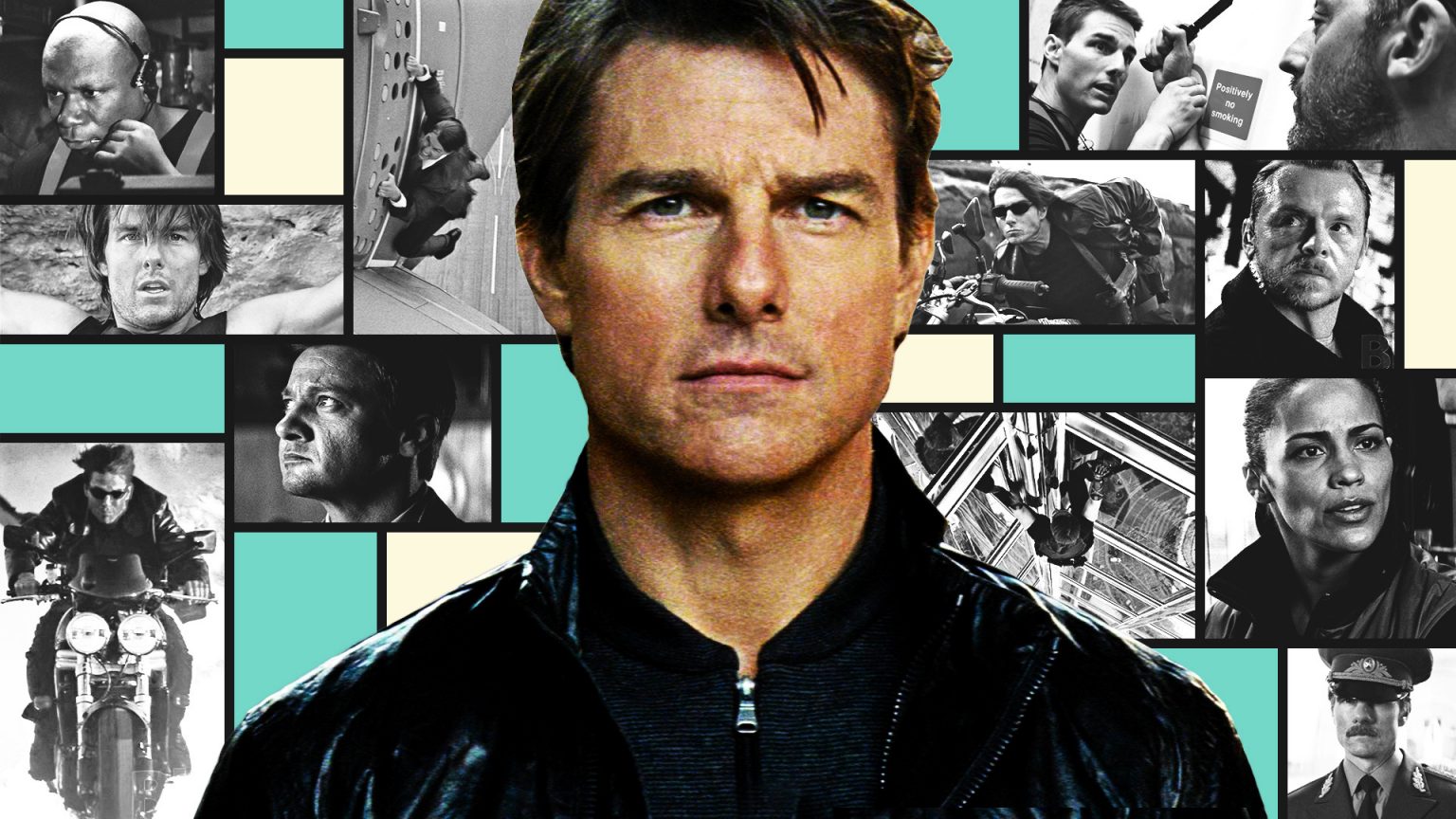

In other words, franchises tend to be marked by significant continuity between entries. In the case of Mission: Impossible, throughlines occur at every level—the face masks, sundry shiny gadgets, and the immortal words: “your mission, should you choose to accept it.” Plot beats also recur (the hazardous heist involving vertiginous heights), as do certain actors like Tom Cruise and Ving Rhames. “Mission: Impossible” is not only a name. It’s a brand, one connoting a carefully calibrated homogeneity aimed at bringing satisfied customers back for more. And yet, the Mission: Impossible films are, when viewed from an aesthetic perspective, anything but homogeneous. Continuity may exist at the level of narrative, but the look and feel of the films are astonishingly variegated—a credit to the fact that nearly every movie is helmed by a different director, whose stylistic signature isn’t erased in favor of a standardized house style (for an example of the latter, check out the post-Phase One MCU movies).

The first film, helmed by pulp maestro Brian De Palma, is filled with rococo visual flourishes such as sharply canted angles, POV tracking shots, and foreground/background juxtapositions that recall the director’s trademark split diopter compositions. In true De Palma fashion, voyeurism plays a key role through characters watching other characters on screens, and at least two gruesome deaths are dwelled upon by the camera for a split second longer than is necessary, harking back to the filmmaker’s propensity for body horror. The second film, directed by John Woo, does an about-face, offering Hong-Kong-inflected, early 2000s bombast brimming with slo-mo, doves, and Hard-Boiled-Esque gun battles.

The third takes yet another turn for the difference. Directed by Alias alum J.J. Abrams, it’s paced like a panic attack, and features an oversaturated color palette that evokes the works of Tony Scott. The fourth film, Mission: Impossible – Ghost Protocol, unfolds under the direction of Brad Bird and is a spry and playful affair, featuring the series’ most elaborate gadgets and a bouncy score by Michael Giacchino, rendering the film a spiritual sequel to Bird’s The Incredibles. Last but not least, with Mission: Impossible – Rogue Nation, Jack Reacher helmer Christopher McQuarrie creates the consummate example of classical action-movie craft, applying efficient pacing and Cold War-style paranoia to a steady stream of epic-yet-intricate set pieces.

Having a mix of sameness and variation within a body of work is not new. So-called “auteurist” cinema banks on such an ethos, with the label implying an idiosyncratic film style persisting across various, otherwise largely separate works. Most lucrative franchises require each successive entry to be novel enough to pique customers’ interests, but not so novel as to deviate from the brand. The Mission: Impossible films are different. Contrary to the traditional auteurist cinema, it isn’t an individual director’s style that forms the series’ connective tissue but rather the de-individualized, seemingly autonomous world/product/entity that is Mission: Impossible. Neither do any of the films operate by conventional franchise logic since the aesthetic variation that exists across installments far exceeds the optimal level of diversity called for by capitalism.

It is important to distinguish the Mission: Impossible films from four other types of franchises that notably mix brand continuity with auteurism and/or stylistic sameness. The first is the rare case, where a director’s distinctive style becomes the brand itself, such that filmmakers end up having enough clout to funnel millions of studios’ dollars into whatever project they want—case in point, Christopher Nolan. The second is the series that’s only nominally a series; films that share a franchise name but are only superficially related to each other at the level of narrative and style (e.g. the Hong Kong series SPL). The third is the anthology series, which inverts the Mission: Impossible formula by deploying continuity of style and discontinuity of narrative across entries. The fourth is the franchise reboot that involves a new director stepping on board and giving the entire series a stylistic makeover, emblematized by Nolan’s Batman Begins and Zack Snyder’s Man of Steel. In such a case, characters and fictional milieus may return, but reboots are, indeed, about “rebooting,” and hence aesthetic discontinuity is par for the course rather than a striking gesture as with Mission: Impossible.

The first three franchise subgenres are relatively rare exceptions to the norm, and the last instance, though fairly common, is premised on a break from the past in such a way that aesthetic discontinuity can happen without seeming unusual. Unlike all these, the Mission: Impossible films conform to the normative franchise model but then stretch its seams to their breaking point. The resulting series feels almost subversive, in the way that it co-opts the Hollywood franchise apparatus and turns it into a testing ground and showcase for the artistic propensities of individual directors.

It’s a huge part of what makes the series so fun and the reason why Christopher McQuarrie’s return for Fallout, though on the one hand hugely exciting given that his Rogue Nation is arguably the best in the series, is also a slight disappointment. Based on Fallout’s trailer, the new film looks to be aesthetically aligned with Rogue Nation, which suggests more cleanly shot, jaw-dropping stunts, while also gesturing toward franchise consistency. Still, given that the series has walked the tightrope between continuity and difference for the past two decades, producing not one bad film and several excellent ones (a feat as precarious and impressive as anything Cruise has pulled off), the Mission: Impossible films deserve nothing less than our trust. And based on early reviews, it seems that the latest entry is another roaring success.