Jack Palance had appeared in only a half dozen films at the time of Man in the Attic (1953). Panoramic Productions, a new independent company set up by Hollywood veteran Leonard Goldstein, chose him to star in their maiden voyage, a remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s silent classic, The Lodger. As the rooming house guest who might be Jack The Ripper, Palance seemed perfect, though America balked at a British case that was already more than 60 years old, and a movie that had already been remade less than a decade earlier in 1944. Moviegoers of the time wanted big, sprawling epics, not dusty period mysteries.

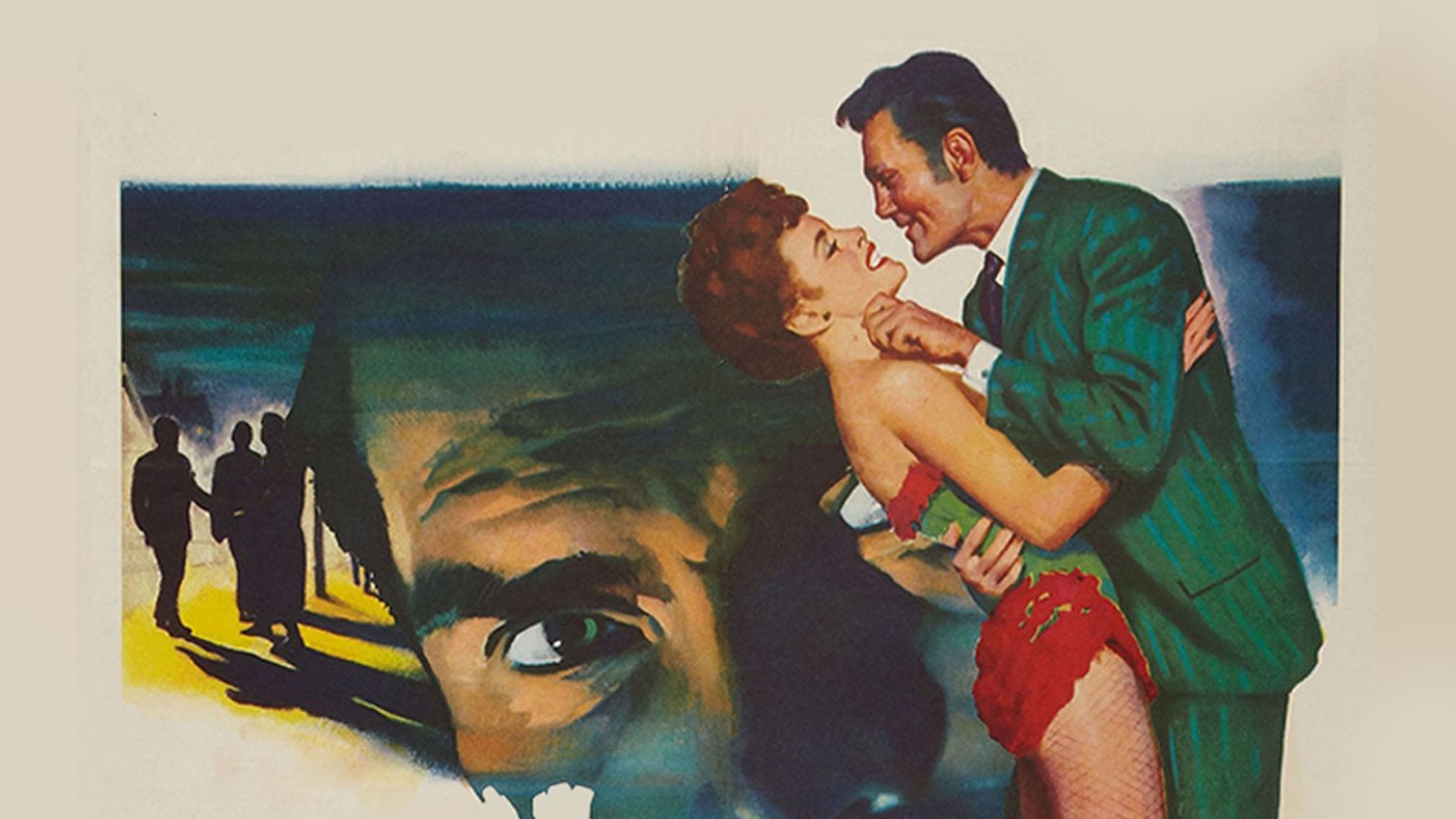

Man in the Attic had the misfortune of competing with Marilyn Monroe and flying saucers and whatever else was lighting up movie screens that year. The craft of director Hugo Fregonese, however, is first rate, as is Palance’s performance. He hadn’t been the producers’ first choice – James Mason had come close to signing on – but Palance was already known for playing heavies. It is hard to believe audiences didn’t storm theater lobbies to see him as Slade, the suspected Ripper. The publicity stills alone were irresistible, with a wolfish Palance looking as if he might devour his pretty co-star Constance Smith in one bite.

In the movie, Slade arouses suspicion after taking a room in an older couple’s home. That he’s never around on the nights when local ladies are being butchered is enough to get people talking, as is the blood on his clothing. Despite the potential for gore, most of the movie’s impact comes from Palance’s granite face and sweaty brow. That same year he’d appeared in Shane as a bullying gunman, seeming too large, too weird, to be a figure from the Old West. Here, he seems too weird for old London, his hair slicked back to highlight the eyes that sit deep in his oversized head, and the sinister air he projects through them. Lust and madness seep from every pore.

In ways that are unexpected, Palance shows the Ripper to be more neurotic than bloodthirsty. He’s strange from the moment he meets his new landlady, claiming the pictures in his room are staring at him. We never see Palance kill, but we see him during the aftermath. He looks to be falling apart, worn down by an inner struggle.

Showcasing such a fragile ripper doesn’t make Man in the Attic less fascinating. Visually, it is the London we know from Sherlock Holmes movies, with ludicrous fog and policemen carrying lanterns (shot by two time Oscar nominee Leo Tover on a set leftover from Orson Welles’ The Magnificent Ambersons). Though the murders take place in the horribly deprived Whitechapel district, we never go there. Instead, we’re treated to elegant playhouses and cozy fireside discussions about murder. Palance shambles through each of his scenes like a big, nervous cat, gently pawing an old Bible, making dark declarations about the beauty of women. There’s a crude attempt to explain the Ripper as a man who detested women for putting their looks on display, and therefore “cutting away” their beauty. This idea doesn’t really work – the real Ripper victims were sad old drunks who had resorted to prostitution, not sassy young chorus girls – but Palance is riveting. At one point, with his blade to a victim’s neck, his face contorts as if he’s in agony. Palance does the impossible – he presents Jack the Ripper as almost worthy of sympathy, a haunted soul.