“Okay, who is this guy?” wondered jazz legends Steve Kuhn, Clark Terry, Bob Brookmeyer and many others of their ilk when budding filmmaker Kristian St. Clair came knocking in 2000, well-worn vinyls in hand, asking questions about rhythm, melody, methadone and Gary McFarland. Determined to learn everything he could about the musical maverick—enormously successful during the 1960s as a startlingly original arranger and composer, yet criminally overlooked in ensuing years following his shadowy death in 1971—St. Clair played detective with a digital camcorder, and set about restoring McFarland’s rightful reputation as a soft samba swinger and hard jazz hero in the haunts of Greenwich Village and far beyond.

The resulting feature-length documentary, the snappy and surprisingly poignant This is Gary McFarland, was well-received on the festival circuit in 2007–08. St. Clair wasn’t entirely satisfied with that version, however, and continued to work on the project, gathering additional archival materials and further shaping his story of the suave, sophisticated maestro who in 1963 The New Yorker called, “the most gifted arranger since Duke Ellington.”

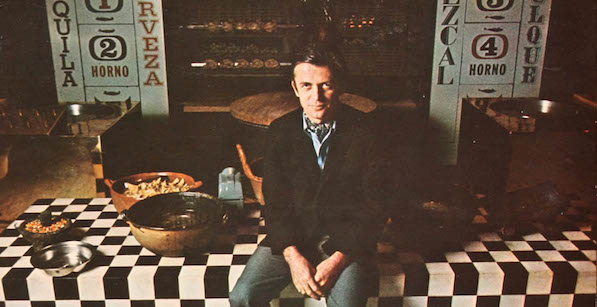

In its now-complete and rereleased form, St. Clair’s film celebrates McFarland’s jam-session-packed life—he performed with Gerry Mulligan, Stan Getz and Count Basie, released more than thirty albums, and scored the little-known British chiller Eye of the Devil and the even more obscure oddity Who Killed Mary Whats’ername?—while circling around his mysterious death. How did this devilishly handsome, blazingly accomplished jazz dynamo and devoted family man end up dead of a methadone overdose in a seedy midtown Manhattan bar at age 38? Far more than a cautionary tale about burning the candle at both ends, This is Gary McFarland is an elegant and elegiac entry in the “behind the music” genre.

As the founder of Century 67 Films, St. Clair has worked with jazz trombonist Grachan Moncur III and gleefully unclassifiable guitarist Bill Frisell. He’s currently in production on a documentary about producer-arranger Jack Nitzsche. St. Clair recently spoke with me via phone from his home in the Central District of Seattle, where he lives with his wife, their two children and a sizable record collection.

Steven Jenkins: When did you first hear Gary McFarland’s music?

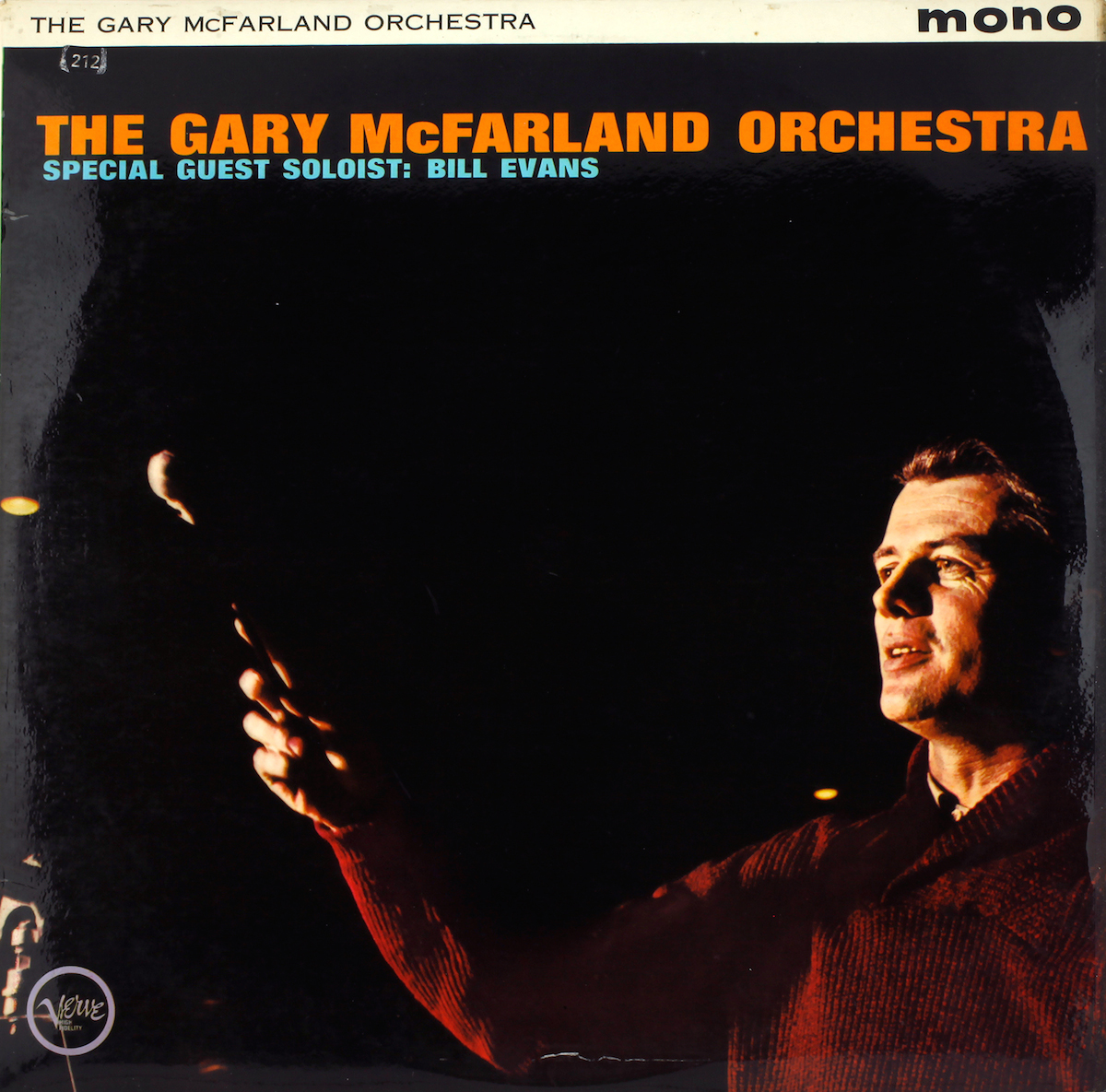

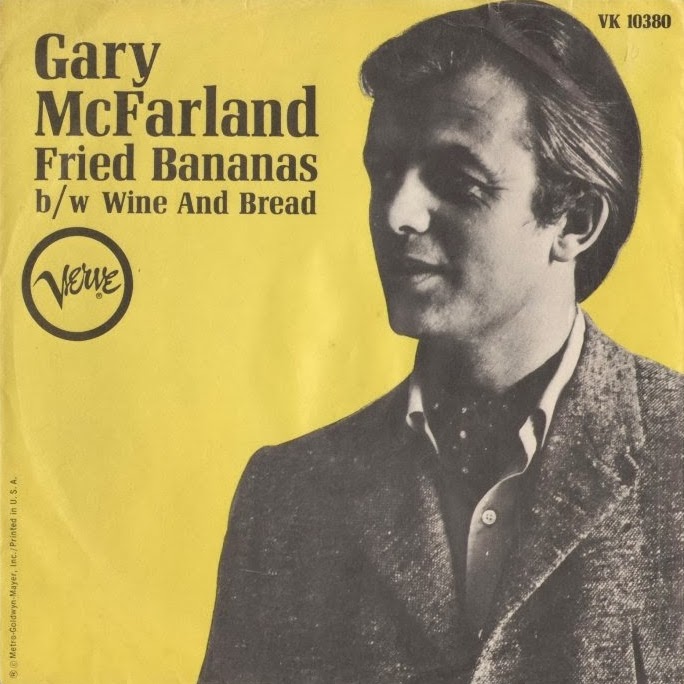

Kristian St. Clair: I’ve been a lifelong record collector, and always a big fan of jazz. I was very much into the Gil Evans and Miles Davis recordings from the 1950s-’60s, their orchestral jazz stuff in particular. I discovered Gary’s music in the early ’90s through an Impulse! Records reissue that paired a Gil Evans record with a McFarland record. I was blown away. The music was very cinematic and modern, led by a jazz orchestra but also with the electric guitar of Gabor Szabo—a totally unique performer in his own right—that gave it a contemporary edge. From that moment on, I picked up every McFarland album that I came across. Some are more heavy jazz, some are more pop. I loved them all.

I started to research McFarland’s story and couldn’t find much information other than that he died young under mysterious circumstances. When he burst onto the scene in the sixties he was quite successful, very prolific, worked with a lot of heavyweights, played all the major jazz festivals, and was even on The Tonight Show a couple of times, but he completely fell through the cracks after he died. That was a head-scratcher: How had this guy who was so successful, whose music was so ahead of his time, became merely a footnote in music history?

Jenkins: So you set out to solve the mystery. Were you daunted by the prospect of making your first feature?

St. Clair: I majored in broadcast journalism and made some short docs in college. Desktop filmmaking was really starting to break through in the late nineties, so I took some classes at the 911 Media Arts Center here in Seattle, learned how to use the Canon XL1 camera and Final Cut Pro, and thought that I could pull off a film on McFarland with fairly limited resources. I was off and running, and started the first round of interviews for the film in 2000.

Jenkins: Were folks eager to reminisce about McFarland?

St. Clair: On my first trip to New York I met with Steve Kuhn, Sy Johnson and several other key figures who knew and worked with him, as well as with McFarland’s widow, Gail, and her family. One interview led to the next…’You should talk to so-and-so’…Clark Terry, Phil Woods. As a jazz fan, it was wonderful.

Jenkins: You never know how it’ll go when you talk to someone whose work you’ve admired for so long, but it seems that you established a nice rapport with the musicians, and also with McFarland’s family members.

St. Clair: People can be wary when you start asking questions, especially when you turn the camera on. ‘Okay, who is this guy?’ But in the course of the interviews they could tell that I had genuine knowledge and interest in their stories and in doing justice to McFarland. When you’re dealing with touchy subjects, like his substance abuse, sometimes people don’t want to talk. I’m not a ‘gotcha!’ filmmaker, so I didn’t push too much. But even hearing ‘I don’t want to talk about that’ during an interview informed the film and the story I wanted to tell.

Jenkins: The details of McFarland’s death remain murky. It was seemingly brought on either by a suicidal final fix or by downing a cocktail unknowingly dosed with methadone in a sinister prank by Mason Hoffenberg, co-writer of the novel Candy with Terry Southern. What conclusions have you drawn?

St. Clair: It’s hard to say for sure exactly what happened. It’s no secret that Gary had substance abuse issues, so it’s not out of the realm of possibilities that he knowingly took methadone and overdosed. He was a good husband and family man, and from all accounts was mellow when he was at home in Long Island, but the demons of temptation and addiction would kick in whenever he went into New York City for recording sessions. That’s when he’d go down the rabbit hole. But he died on election night; Gail was very involved with the Democratic party, and he was supposed to help her out that night, so it seems strange that he would choose to kill himself just then.

In any event, the incident was never accurately documented, and there was definitely a cover-up. His death certificate says he died from a fatty liver, but it’s common knowledge he died of a methadone overdose. The bar owner probably paid off the police to look the other way. I dug deeper and found references to David Burnett, the other person who died that night [presumably also by knocking back a drink laced with methadone]. He came from a prominent New York literary family. There are no references to Gary in the write-ups of Burnett’s death, even though they both died in the bar that night. It’s very strange. The whole thing is like Rashomon; there’s a kernel of truth in everyone’s version of the story.

Jenkins: Given McFarland’s tragic death, speaking with his widow, Gail, must have been difficult.

St. Clair: We met at her home, and it was a tough time because their son had passed away from a heroin overdose about six months earlier, at the same age as Gary when he died. She gave me her blessing to make the film, and access to her personal photos.

It was a long journey from those early days of interviews and production to screening at festivals in 2007–08. I knew that the film wasn’t quite done, that there was more footage I wanted to incorporate, so I went back to it in recent years.

Jenkins: Were you on the hunt for particular archival footage?

St. Clair: I knew about McFarland’s TV news appearances and Tonight Show guest spots, but all of those old tapes had been erased. I kept searching for footage of him in action, and discovered his performance with Stan Getz in the UCLA Film and Television Archive. I also found footage of his wedding. All along, various people mentioned that McFarland had been in a Fresca commercial, and that’s what I really wanted to find. A lot of musicians made good money in the sixties writing jingles for TV commercials. McFarland was active in that world, and he composed a jingle for Fresca and appeared in the commercial, conducting the band in the studio with snowflakes coming down over everything; Fresca’s slogan back then was ‘It’s a blizzard.’ I learned that Coca-Cola had donated all of their old commercials to the Library of Congress, where they were in the midst of being digitized. I contacted the Library of Congress a bunch of times, but they couldn’t find the footage and weren’t very interested in prioritizing this one commercial just so that I could use it in my film. Eventually, Coca-Cola decided to relaunch Fresca, so those tapes ended up on the top of the stack. Even then I had to wait for years to satisfy Coca-Cola’s legal requirements before I gained permission to include the commercial.

With that footage and with the licensing of more photographs, I reworked the film with the help of an editor, brought it up to 2014 standards and started to screen it again. I could finally just sit back and watch the film objectively and enjoy it and not cringe.

Jenkins: Did you look closely at music documentaries over the years while making the film?

St. Clair: I’ve always loved Jazz on a Summer’s Day, and Bruce Weber’s film on Chet Baker, Let’s Get Lost. One that I think is really ahead of the curve in the music doc genre is Brian Wilson: I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times, directed by Don Was.

Jenkins: Your film is visually rich, with beautiful archival footage and colorful illustrations that evoke a certain sixties hipness and optimism. How did you come up with this look?

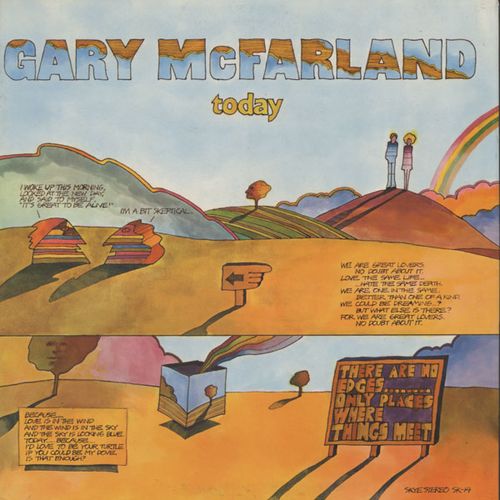

St. Clair: A lot of that stuff was inspired by a series of children’s books on different international cities by the Czech artist Miroslav Šašek. This is New York was one of my favorite books as a kid. Sasek’s sixties art seemed like a perfect match for McFarland’s music. The album cover design from that era never ceases to amaze me, so I looked at that as well. You have to limit yourself to one or two key visual elements, or else the film won’t hold together.

Jenkins: McFarland’s music definitely holds it all together. Hearing snippets of his later works, like Soft Samba and America the Beautiful: An Account of Its Disappearance, it’s easy to imagine that he would have continued to explore uncharted musical terrain and influence all kinds of musicians.

St. Clair: I think he would have been totally stimulated by where music headed in the 1970s. Every once in a while I hear something that sounds like him. Johnny Echols, who played guitar in the band Love, recently mentioned that [visionary Love singer-songwriter] Arthur Lee brought Soft Samba into the studio and used it as the template for the band’s second album. Stereolab and Super Furry Animals were also into Gary’s music. More recently, remember that noxiously ubiquitous song ‘Young Folks’ by Peter Bjorn and John? That whistling thing is totally Gary, it sounds just like his song ‘Flea Market.’

My hope with this film is that more people will begin to recognize and talk about Gary McFarland as one of the great jazz figures of the era along with Gil Evans and Oliver Nelson, as people eventually acknowledged Billy Strayhorn’s work with Duke Ellington after years of being ignored and forgotten.

Jenkins: And now you’re working on a film about another long-neglected music legend.

St. Clair: I love composer-arrangers, and shedding light on figures who were completely instrumental but behind the scenes. Jack Nitzsche was so unique. He worked with Neil Young, the Rolling Stones, Doris Day…the guy was everywhere, and like McFarland had a compelling story and destructive personality. I’ve already interviewed Keith Richards, Ry Cooder, Miloš Forman, William Friedkin and a bunch of other people who knew and worked with Nitzsche, and I’m working on a rough cut.

At some point I’d also like to make a documentary about Sterling Hayden. I also want to make a short narrative film, so pretty soon I’ll get some actors together and give it a try. Whether or not it’ll be releasable, we’ll see.