Since the Stonewall era, queer moviegoers have developed a reputation as both recipients and purveyors of outrage. Gay cinephiles’ high aptitude for reading between the lines of a respectful, straightforward narrative is only rivaled by their exposure to bottom-of-the-barrel representation and intolerance from their fellow audience members: Two notable commercial releases, Brian Dannelly’s 2004 teen comedy Saved! and Ang Lee’s 2005 cowboy romance Brokeback Mountain, drew censorious protests from American audiences for their sympathetic depictions of homosexuality. Fifteen years later, viewers still remain hard-pressed to engage with a title featuring queer characters without encountering at least one critique that has more to do with “morality” than mise-en-scène.

On the other hand, the LGBTQIA+ community is adept at mobilizing en masse against the cinematic depictions that it personally finds inadequate or diabolical. Collectively, the years between 1980 and 1992 offer a thumbnail sketch of the tumultuous state of affairs for queer people, from pre-AIDS decadence to the crushing oppression of political indifference to a terrifying global epidemic and the murder of a gay naval officer that would expedite the “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. An increasingly vulnerable community focused unprecedented anger on three of the era’s moving pictures—all, tellingly, crime thrillers—for their careless portrayals of homosexuals as delinquents (and in two instances, indiscriminating strumpets) during a lethal culture war: William Friedkin’s Cruising in 1980, Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs in 1991, and Paul Verhoeven’s Basic Instinct in 1992. Historically, the protests were and remain three of the most aggressive and effective grassroots campaigns against film productions in the United States. However, perhaps because the lure of the forbidden is a textbook narrative device about and for gay culture, it’s admittedly satisfying to examine this trio of beleaguered gumshoe flicks as a gay person from a much younger generation. From a safe distance, and with the support of a historical lens, they offer the nascent viewer visual pleasures that were denied to their original queer audiences.

Cruising (dir. William Friedkin, 1980)

Set in the armpit of a long-gone, leathered-up New York City and loosely based on a true story, Cruising follows an undercover cop, Steve Burns (Al Pacino), searching for a grisly serial killer who puts the “butch” in butcher, dismembering his conquests post-coitus and tossing their limbs into the Hudson River. To catch the killer, Burns immerses himself, perhaps a bit too ardently, in gay culture. While Cruising’s production was repeatedly foiled by gay New Yorkers who were furious with having their dark S&M clubs professionally backlit and sold to the masses as a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah, the joke is ultimately on the era’s gay panic: Officer Burns’ weakness shows as he leaves his shift to immediately shower or theatrically make love to his girlfriend (who serves little purpose other than to assert Burns’ heterosexuality to viewers of similar persuasion). At times, the film seems too titillated by its own immoral setting to form coherent plot points, let alone an adequate ending.

Part of Cruising’s unfavorable debut can be attributed to its gore, which exclusively appears after a man grazes, or attempts to graze, another man. Ironically, the outrage over the film’s implication that a horrifying death is a reasonable consequence of casual sex might have been tempered had it featured…more sex. Deemed inappropriate to screen, nearly an hour of footage shot in the Meatpacking District bar scene was lost or destroyed. Had those scenes been included, they may have cushioned Cruising’s brutality. In fact, it’s those particular moments—once gawky and exploitative, now erotic and nostalgic—that today’s viewers most associate with Friedkin’s movie. When extracted from Crusing’s already-slim context, they more closely resemble a pre-AIDS, pre-Grindr fantasy than they do a cesspool of abomination. There is actually a 2013 experimental film about Cruising’s lost footage, Interior. Leather Bar. Day, that tackles this idea of gay propaganda’s shifting meanings.

The Silence of the Lambs (dir. Jonathan Demme, 1991)

Before the story of underdog FBI trainee Clarice Starling—who white-knuckles her way through the Midwest on the trail of a misogynistic serial killer—became the record-making darling of the 1992 Academy Awards, The Silence of the Lambs made gay filmgoers seethe for its self-loathing, cross-dressing psychopath, Jame Gumb (Ted Levine), who many viewed as a vicious parody of queer men. Several months after the film’s New York premiere, the activist Douglas Crimp gave a speech at Columbia University where he observed, “What makes the debate about Silence so unsettling is the fact that it is divided along with gender. Dykes love it for its positive feminist portrayal of Clarice Starling [Jodie Foster], but gay men hate it for the representation of Gumb and Hannibal Lecter [Anthony Hopkins] as serial killers.” A line in the sand had been drawn. Around that same time, wheatpaste posters began appearing around the city, outing the film’s lead. As the Academy Awards loomed, west coast activists planned to stage a protest opposite the ceremony’s venue. Their grievances included Silence’s continued acclaim, Best Picture nominee JFK’s sniveling portrayal of the gay conspirators who attempted to assassinate Kennedy, and the snubbing of gay indie newcomer Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho.

Today, Clarice still has clout as one of the most inspiring female protagonists ever written. Gumb seems inconsequential when compared to Hannibal’s flamboyant anti-hero sensibilities and enviably refined palate; Gumb’s gender performance to “Goodbye Horses” (still a much-covered anthem of eccentricity) could be interpreted as camp, paling in comparison to any episode of RuPaul’s long-running and commercially successful reality show Drag Race. Nowadays, the concept of ‘tucking’ is familiar to housewives the world over.

Basic Instinct (dir. Paul Verhoeven, 1992)

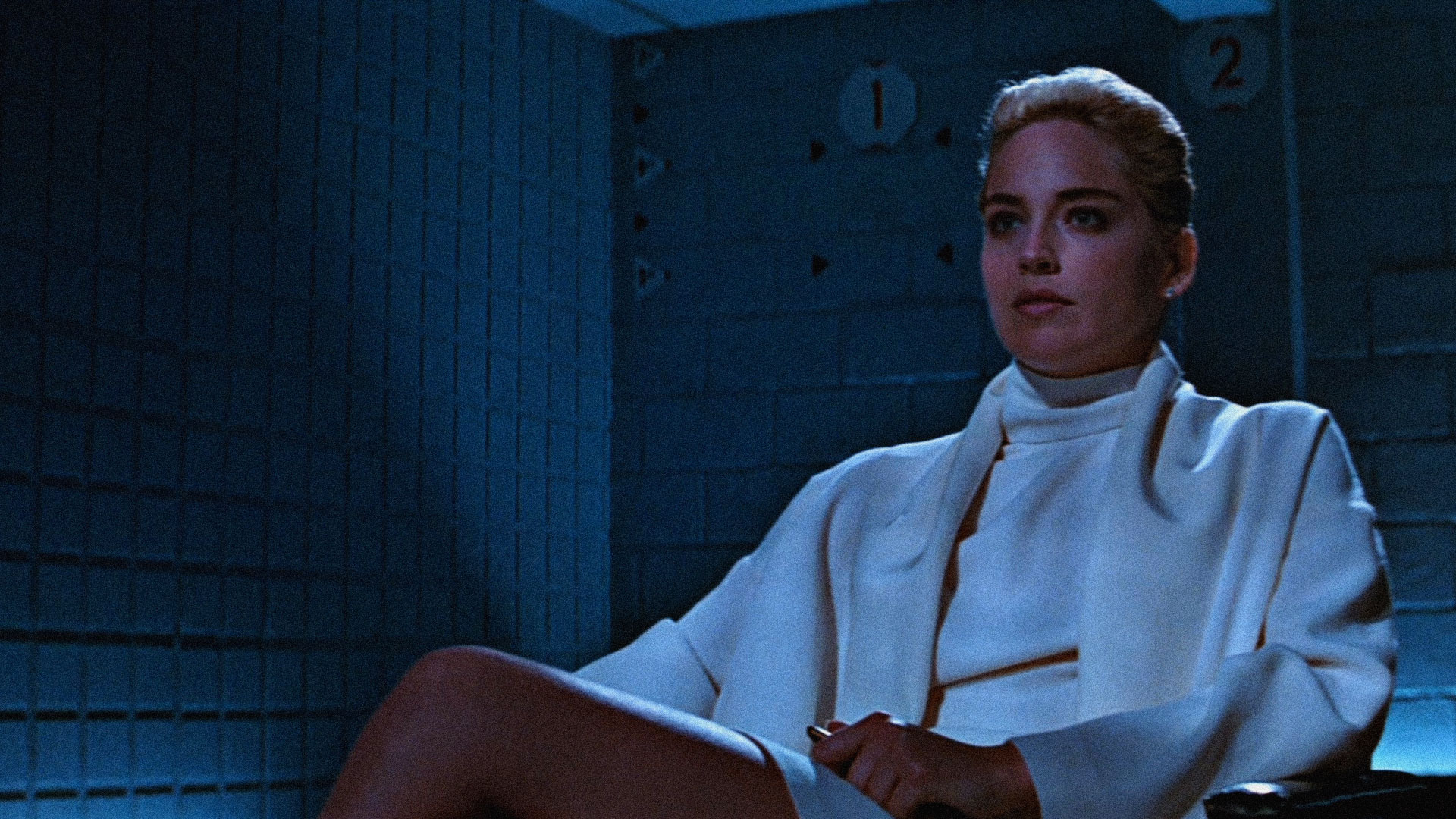

In Paul Verhoeven’s bar-setting neo-noir, dirty cop Nick Curran (Michael Douglas) grows obsessed with pinning author Catherine Tramell (Sharon Stone), the primary suspect in a series of crisply executed murders. Curran is no match for Tramell’s imagination or sexual appetite; he soon finds himself tasked with unraveling her love life even as he becomes a part of it. Along the way, he discovers her myriad female lovers, two of whom die before the film’s finale.

The parallels between Cruising and Basic Instinct are notable, even if they don’t extend further than the narratives and ambiguous endings. Tramell’s lover, Roxy (Leilani Sarelle), who makes an amusing attempt to mow Curran down with her sports car, seems to be a West Coast variation on Friedkin’s gay men: leathered up, lusting for blood, and in possession of a death wish. Yet Basic Instinct is what Cruising could have been had Friedkin been willing to become intimately acquainted with the subculture over which his film obsesses; just as Cruising is what Basic Instinct could’ve been had Verhoeven and screenwriter Joe Eszterhas, who received an unheard-of three million dollar sum for his snappy script, treated lesbian and bisexual women with fear rather than perpetual arousal.

The LGBTQIA+ activists who protested Basic Instinct picked up on these similarities, too. “There were some really feisty women who were like, ‘This is our Cruising,’” one of the original picketers told Yahoo! two years ago. In his book Movie Censorship and American Culture, Frances G. Couvares writes, “The night of the Basic Instinct premiere, demonstrators blew whistles, passed out leaflets, and carried placards reading, ‘Kiss My Ice Pick,’ ‘Hollywood Promotes Anti-Gay Violence,’ and ‘Save Your Money—The Bisexual Did It.’”

The sexist fantasy, however, betrays its creators in the long run. Michael Douglas is more of a cuckold than he is a fathomable romantic lead. Meanwhile, Sharon Stone’s once self-exploiting character now reads as utterly impenetrable—no matter who is in her bed, one should be so lucky to get to study at her feet.

Articulating a secret enjoyment of films that have been thorns in the LGBTQIA+ community’s side is as precarious as it is pleasurable; one risks disrespecting the fruits of our predecessors’ labors. In reality, it’s thanks to their wheat pastes and whistles that new queer cinema offered us alternatives to the unfeeling stereotypes of major studio releases. We have the choice of enjoying both the pristine hero and the monster, as the monster is no longer the default. Because there are satisfying alternatives to Cruising, The Silence of the Lambs, and Basic Instinct, these films have been permitted a “cooling period,” after which they can be examined for what they are, rather than simply for their most-noted inadequacies—and sometimes, what they are in this very moment is delightful.