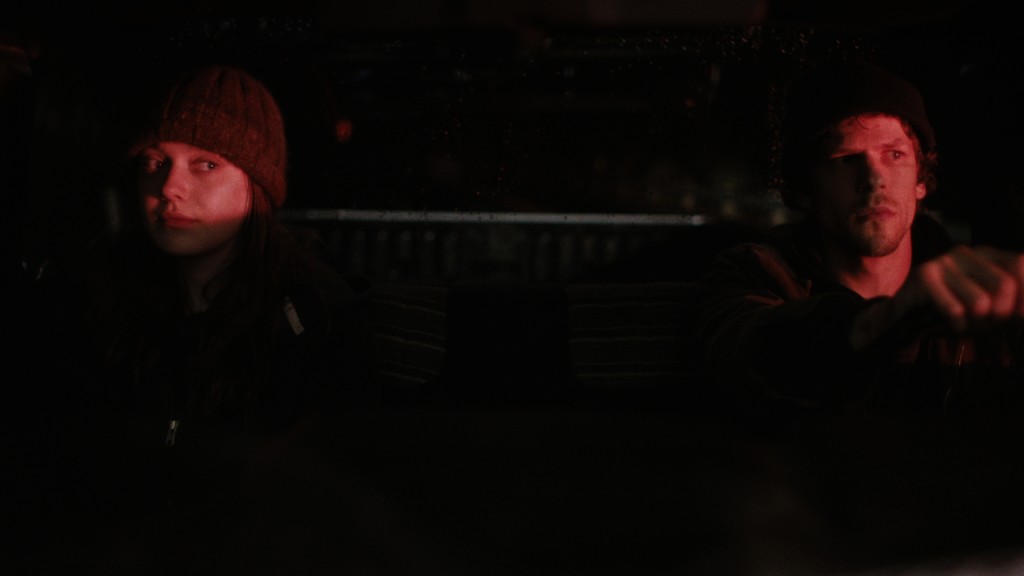

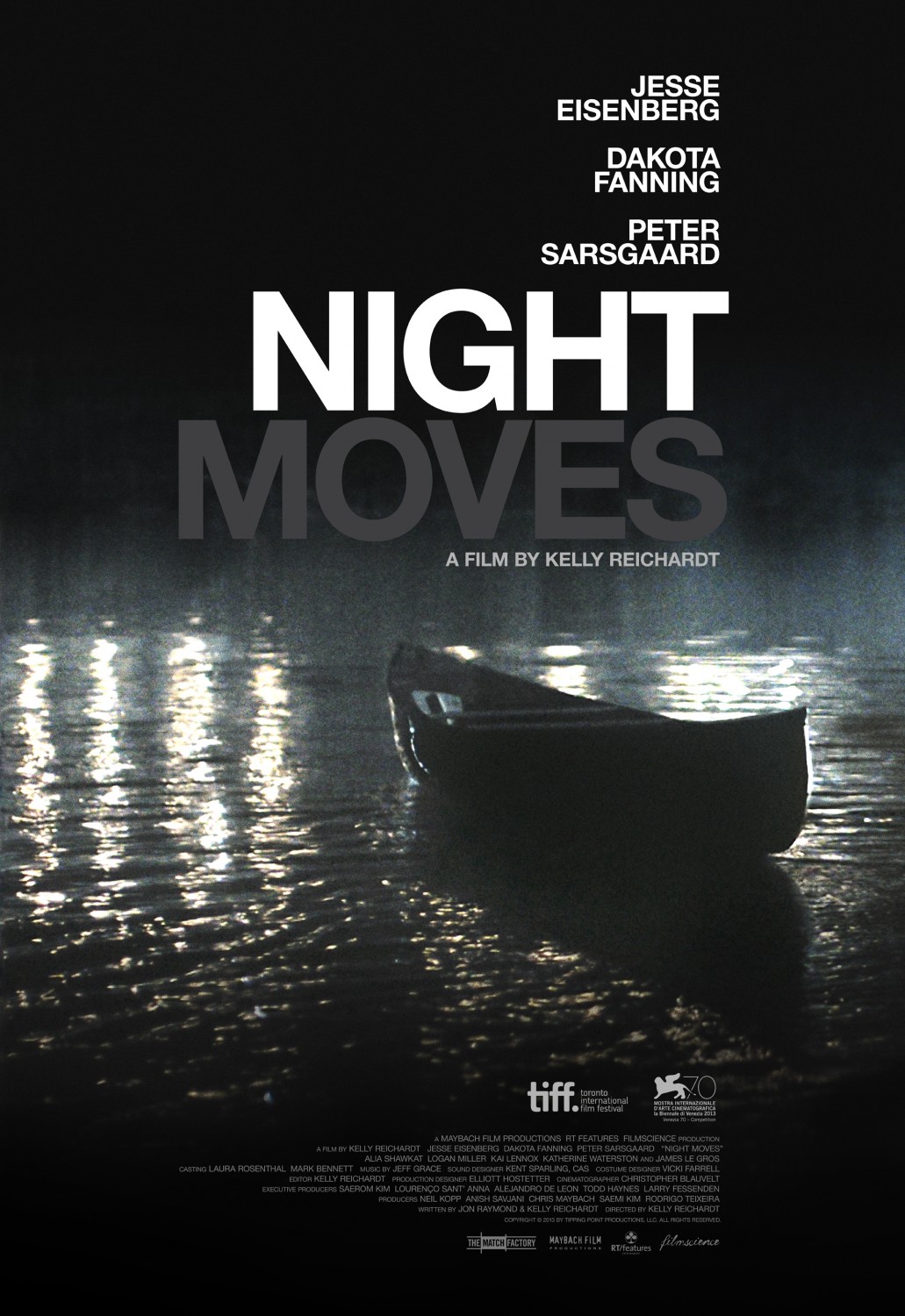

In Night Moves Jesse Eisenberg, Dakota Fanning and Peter Sarsgard play three environmental activists, who, for different reasons, decide to blow up a local dam. The new project from Kelly Reichardt (see also: “Kelly Reichardt: Genres, Geographies and the Evolution of a Filmmaker”), acclaimed independent director of Wendy and Lucy and Meek’s Cutoff, investigates the relationship between people involved in drastic, violent act. Just like in the latter movie the western genre gained more intimate, focused, psychological perspective, Night Moves can be perceived as “indie thriller,” concerned with inner turmoil rather than outside danger. How much of a burden can a radical act place on one’s mind and how can it affect the others? During our conversation at Venice Film Festival 2013, Kelly Reichardt addressed these issues, as well as the ever-present danger of disengaging the audience.

Keyframe: I was wondering if the ecological activism is at the center of Night Moves, or is it actually the thriller aspect, or maybe the Raskolnikov-like persona that Jesse Eisenberg plays, or maybe it’s just a mixture of all these things.

Kelly Reichardt: What did you come up with?

Keyframe: I couldn’t decide.

Reichardt: Well, I don’t know either, to be honest. It’s funny, making a film is such a long process, day to day, and you sum it all up as if there was a direct line of events. Which isn’t really the way it happens. So I’m not sure, it could be all of the above, I guess.

Keyframe: But there must have been a main intention, driving thought.

Reichardt: I think we wanted to make a character film and we were also interested in particular region, down in southern Oregon. So those were the initial ideas, and then we had the idea of making a sort of small-tea thriller.

Keyframe: Your previous film, Meek’s Cutoff, represented a different way to look at western. Night Moves does similar thing with thriller. How conscious was the idea of following or not following the rules of the genre in the filmmaking process?

Reichardt: Filmmaking is a very conscious. Usually in the writing stage I don’t think about genre, I’m mostly interested in characters and place. But in this case it started with a short love story that took place on a farm, involving someone hiding there after committing some radical environmental act. I read this story about two years ago, so I can hardly say I remember everything about it. I liked the idea of the secluded world of the farm and someone hiding there. Then we told ourselves ‘let’s do a caper,’ but like Rififi, where the movie actually stops at some point to show a process itself. I loved the detail in that film, how they showed what it takes to plan and execute a break-in. You know, the little things, like drilling and having to wrap the shirt around the drill to keep it quiet. So we just got on board with the genre idea, even during the writing, and certainly in actual filmmaking.

Keyframe: Did you want to make any political point about ecology?

Reichardt: No, there’s no agenda here. My producers have both lived in Oregon all their lives, and that northwest region has a long history of environmental activism. When I’m driving from New York to Oregon, and I’m traveling through a certain part of the country called the Bible Belt—this land with a huge sky, tornados and so on—I think I understand their religion. I think if I lived there, I’d also be religious. I just understand why in this landscape God would exist in your life. In the same way, when I’m in the northwest, I can understand why it’s a hot bed for environmental activism. The destruction of the forests is visible in everyday life, the clear cuts are everywhere, the politics of the city life clashes with the interests of the logging community. When you see a train passing by with tons of cut trees, you can understand their activism, and you can relate to them, because there’s nothing sadder than watching those trains. When we were shooting, we saw a lot of people enjoying camping and water-sports on this beautiful reservoir. But you’re aware it was once a forest, and you ask yourself what’s the cost of our entertainment. The film is also an investigation into a lot of young kids who put their lives on the line, trying to give some resistance to destruction of environment. And they’re being severely punished, they’re going to jail for a very long time. Even property destruction is considered as terrorism. These stories are interesting, we didn’t want to make a message film with hard-line politics, we wanted to make a film about characters, people involved in activism for different reasons, upsides and downsides of radical act.

Keyframe: So you didn’t feel obliged to follow certain rules regarding research, like interviewing activists and so on?

Reichardt: No, but research is really interesting, and we talked to some people. But they they were protective of their way of living and suspicious of the idea of depicting it in a movie. A lot of people were really generous, but they also wanted us to understand how important this particular way of living was to them. Many people we met really manage to live in a self-sustained way, without using resources they don’t condone. They use solar energy, they share food, grow crops and so on.

Keyframe: One of the pivotal scenes in the movie is the community meeting, when they screen environmentalist documentary. Is it a depiction of how local activism, rather than big political decisions, can be a catalyst for change?

Reichardt: Well, above all, it’s one of many nights in the life of Josh, Jesse Eisenberg’s character. All these community meetings are kind of bullshit to him, just people talking about their good intentions. For him that’s not enough. This scene presents different approaches to the problem: one person stresses the importance of coming together, other person says it’s important that everyone takes care of environment individually, on their own backyard, someone else, Josh for instance, says ‘Fuck that, we have to actually do something’.

Keyframe: Do you think violence can be treated as a tool to achieve social goals, or should it be generally condemned?

Reichardt: I certainly don’t have any answers. If you study history of well-meaning grass roots groups—The Weather Underground, Earth First, the ELF, Black Panthers—you can see that at a certain point the amount of violence or radical acts starts to eat you from the inside. The paranoia and isolation seem to make these groups crumble. But maybe they’re supposed to live only for a moment, maybe they’re not supposed to have long history, especially if they’re based on anti-institutional idea, like the Occupy movement. But when I read about radical acts, part of me goes ‘all right!’, even though I wouldn’t do it myself. You can’t help wondering what’s the answer, what would it take to make a change—writing a letter may not be the most effective way.

Keyframe: Music plays an important part in your film, can you say something about the choice you made in that department?

Reichardt: The composer is Jeff Grace, with whom I worked on Meek’s Cutoff. I like his work very much. He plays mostly electronic stuff, he does everything by himself, in his tiny New York apartment. He distorts the sound of instruments, for example by putting rocks under strings. He also does a lot of stuff on his keyboards, a lot of it synthesized. He’s a one-man band and I never really know what goes on in that little room.

Keyframe: His sound is a sort of Brian Eno-ambience universe, but there’s also interesting pop music at the end.

Reichardt: Yeah, a really bad pop music. Maybe I shouldn’t have said it’s bad…I tried to find the most mainstream thing I could afford, basically.

Keyframe: Well, I kind of liked it.

Reichardt: Did you? Throughout editing, I kept picking songs, because there were several I couldn’t afford to use along the way. They sort of offended my ears when I started, and then became guilty pleasures as time went on. But I don’t want to talk about last scene of the movie, let’s not spoil it!

Keyframe: Both Night Moves and Meek’s Cutoff are very steady, slow-paced narratives. Do you prefer this kind of language, because it allows you to dwell into psychological nuances of your characters?

Reichardt: I think this story holds a lot of ambiguities, which really appeals to me, so I wanted a really clean structure to present them. I’m attracted to that kind of filmmaking, and I feel it’s going away, so I want to hold on to it.

Keyframe: What are the other filmmakers attracted to this style in your opinion?

Reichardt: There are some who inspire me, but their work is very different from mine. I love Nicholas Ray, Ozu, Bresson. They are great teachers, it’s good to learn from them, because you watch their films and you go: look, it’s all so easy, simple scene, one lens, we can all do this! But there’s magic in that simplicity. So for that purpose, I like the clean narrative, but I don’t like the word ‘slow’ and it’s coming up very often in interviews.

Keyframe: I didn’t mean it in a bad way.

Reichardt: I know, but when I go to see a movie and I watch the previews, I feel assaulted. I’d prefer if we talked about everything being too fast, and this kind of narrative being a norm. I actually felt like I was making my ‘action-packed’ movie!

Keyframe: Well, they are all relative terms to some extent.

Reichardt: Yeah, that’s true.

Keyframe: Among all the emotions of the characters, fear and panic seem to be the most important ones.

Reichardt: I can relate to those emotions very well. When we were making the film, I kept having a dream in which the crew misunderstood me, and they thought I wanted to actually blow up a dam. It happened, and I couldn’t do anything to prevent it. I’m so terrified about the idea of prison that anything that could put me behind bars even for a night is impossible for me to do.

Keyframe: It must be painful for you to watch Hitchcock films with falsely accused characters.

Reichardt: Yeah, they prove that anything can happen, right? But I hope that with this film, and with the character of young girl Deena, I can get some message across to people her age. It’s the age when you search for meaning, something to do, something to be, and when you find it you are very sure about it. And it’s hard not to get heartbroken seeing that, it’s hard not to think: ‘Oh my god, you’re gonna be crushed later, that’s not gonna last.’ Josh is a bit darker, the male characters are darker in this film, but there are also things about them I can relate to, for better or worse.

Keyframe: Do you think the emotional landscape of the film is somewhat a result of our contemporary political predicament? Even if only by the power of osmosis, not artistic intention?

Reichardt: I do believe that in the course of the movie the dam becomes a symbol of people in power who built it, support it and defend it. The people that main characters see as ‘the other side.’ A symbol in form of a big, brick wall, which is also like a prison. I think the physicality of the space does a lot of ‘symbolic’ work, and that’s why finding the right space is so crucial. It can tell a story for you.

Keyframe: Each of the characters has his/her own reasons, but they’re very enigmatic. There’s a fine line between giving the audience just enough to be interested, but not revealing too much, and actually giving too little and make viewers disengaged.

Reichardt: That’s true, it’s a fine line to walk, and I’ve walked it in all of my movies. Of course you can fall on either side, but I’d rather fall on the vague side, and I’m sure I do that all the time.