[Editor’s note: We revisit this February 2012 interview with Brazilian filmmaker José Padilha as his latest, the RoboCop remake, hits American screens.]

José Padilha’s two fiction features about the police who patrol the frontlines of Brazil’s drug war broke box-office records for domestic films in a country dominated by Hollywood-produced fare. The first, Tropa de Elite (Elite Squad, 2007), earned a $20-million high for Brazil-made films released that year and garnered the Golden Bear Award at the Berlin Film Festival. Its sequel, Tropa de Elite 2 (2010), was the country’s submission for the 2012 Academy Awards and earned an unprecedented $103 million, more than twice the box-office take of the next highest ranking Brazilian-made film, a gender-reversal comedy starring two renowned telenovela actors; almost three times Dois Filhos de Francisco, a fictional account of the lives of two beloved Brazilian musicians; and more than six times 2002’s City of God, the last Brazilian feature to become an international hit.

Still, Padilha says, he would rather make documentaries. In a 2009 interview he told me that he would have made a nonfiction film from the best-selling book co-written by former members of the specialized police force if he hadn’t feared for his life.

Having studied math and physics in school, Padilha later switched from an unsatisfying banking career to filmmaking, figuring that documentaries would allow him to combine his interests in science and reality. “I thought making a documentary would be easy,” he admitted, smiling. He was raised in an elite cultural milieu that included his godfather, playwright Nelson Rodrigues, brother of sportswriter Mário Filho, whose name graces Rio de Janeiro’s storied soccer stadium (nicknamed Maracaña). Rodrigues’s provocative plays are credited with modernizing Brazilian theater in the 1940s and have been adapted often for film and television. Rodrigues’s own sons made films and Padilha’s father, a scientist turned businessman, executive-produced two of them. Padilha explained he “grew up around film sets,” but when it came time to make his own, no decent film school had yet been established in Brazil.

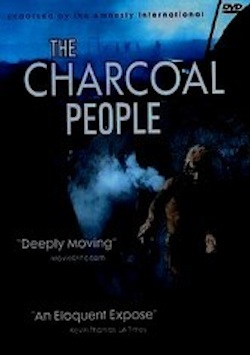

Padilha’s background in finance helped him to maximize the country’s generous tax incentives to fund his first project. Knowing it was difficult to raise money in the U.S. at that time, he enticed Oscar-winner Nigel Noble from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts to direct a documentary based on Marcos Prado’s award-winning photo series about charcoal production. Padilha also was aware of Noble’s impatience for television commissioning editors who interfere in aesthetic decisions. “Nigel was famous for throwing a roll of negative at a National Geographic producer. We recognized the same spirit in each other,” Padilha said. Noble agreed to make The Charcoal People and, at the same time, teach the aspiring filmmaker. “It was a naïve move,” noted Padilha, laughing. “[It] turned out to be the most expensive film school ever.”

The resulting documentary is a beautiful, moving portrait of the laborers who subsist on the making of charcoal and an elegy to the forests sacrificed in the process. It went on to compete at Sundance in 2000. “We thought it was easy,” he confessed of his budding career. National Geographic’s Explorer Channel then commissioned his next project, to be based once again Prado’s photographs. “Initially, [they thought] ‘Who are they? What guarantees these Brazilians won’t take Nat Geo money and run,’” Padilha remembered. He called up Noble and asked him to contact the channel on his behalf. Os Pantaneiros, about the vanishing cowboy culture and wildlife habitat of Brazil’s sprawling wetlands, became the most popular doc on Brazilian TV at the time. Padilha and Prado’s partnership, Zazen Productions, has since yielded award-winning documentaries by both directors, Padilha’s Tropa de Elite features, and, expected in April of this year, Prado’s first fiction feature, Artificial Paradises, about the ecstasy generation.

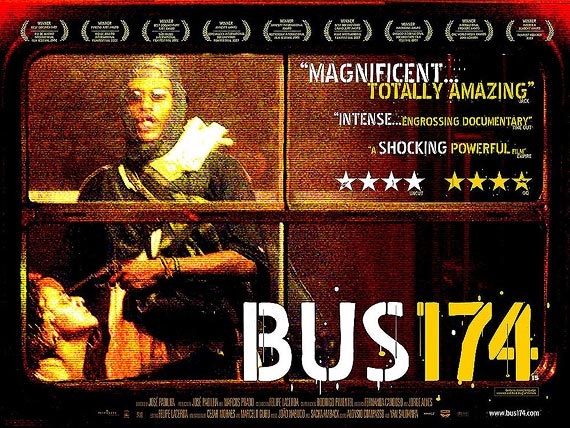

Padilha is still best-known in the United States for the Emmy-winning Bus 174 (2002). The BBC Storyville-commissioned film makes use of plentiful news footage shot of a bus hijacking in Rio de Janeiro, including the image of police shooting and killing one of the hostages. Padilha reconstructed the chaotic scene and intercut it with a narrative of the life of the hijacker, a street kid who had survived the infamous Candelária massacre in 1993. It is not only a skillful condemnation of Rio police’s bungling and cruelty but also revealed to Brazilians, who were prone to vilify the hijacker, the cycle of poverty that led this hopeless young man to violence. It has since been adapted into a fiction film by Bruno Barreto, Última Parada 174 (2008).

Garapa (2009) covers a different kind of systemic violence. Made to put a human face on the statistics of chronic hunger, it follows three mothers in Brazil’s drought-stricken northeastern state of Ceará as they deal with drunken fathers, the prolonged absence of food, and indifference of politicians who would gain little by helping a population who lack the documents to vote. Padilha shot on 35mm black-and-white film using only available light and finished Garapa with no musical soundtrack, creating a kind of poetic cinema of deprivation. The film, named for the mixture of sugar and water used to stave off hunger, bears intimate witness to these families’ heartbreaking reality. Padilha told me that each family’s story unfolds with few temporal liberties taken, as he wanted to avert criticism of trying to magnify the problem in the editing room.

‘Nigel Noble was famous for throwing a roll of negative at a National Geographic producer. We recognized the same spirit in each other,’ Padilha said. Noble agreed to make ‘The Charcoal People’ and, at the same time, teach the aspiring filmmaker. ‘It was a naïve move,’ noted Padilha, laughing. ‘[It] turned out to be the most expensive film school ever.’

After its premiere in São Paulo in 2009, he told the audience: “I get no pleasure showing this film.” Despite its artistry, the film is very hard to watch. One Brazilian journalist wrote after seeing it, “I’m not a masochist, but to take a beating by Padilha has only been good for Brazilian cinema.”

The next beating was sustained by an academic discipline. Secrets of the Tribe, his second BBC commission, is a rat-a-tat-tat juxtaposition of illustrious talking heads debating the accusations of genocide, pederasty and other atrocities leveled at anthropologists in Patrick Tierney’s book-length exposé, Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon. The interviews quickly digress into childish personal attacks. “Anthropology’s methodology is totally flawed. Each anthropologist finds exactly the evidence to fit their paradigm,” said Padilha. “To destroy the data, you have to destroy the person.” The documentary would be comical if the situation wasn’t so tragic for the Yanomami, the native culture that has been the subject of intense study since “first contact” was made in the 1940s. In Secrets, the Yanomami finally get a voice: “You people,” one tribesman says at the beginning, “should be ignorant of us.”

Despite his impressive track record in documentary, Padilha recognizes the benefits of fiction as a wider reaching and more appealing vehicle for conveying what most people prefer not think about: brutality and injustice. Both of his Tropa de Elite films incited spirited discussions in the national media about the use of force by Rio’s BOPE, the elite squad of the title, which has largely been praised by the middle and upper classes who value their own safety first. Last year, when the city began expelling drug dealers from certain favelas and installing an occupation force, Padilha appeared on a panel news show discussing the pacification process. News footage captured during one of the invasions could have been a scene in either Tropa de Elite: a group of unarmed men, some bare-chested, escaping through the tall grass were picked off from a helicopter by police with automatic rifles. Once you purge the slums of drug dealers, I recall him saying on the program, you are left with the police.

Reflecting on Padilha’s body of work so far, it’s tempting to see a parallel with his godfather, no stranger to controversy himself. Unknown in the United States, Rodrigues wrote what he called “unpleasant theater,” plays that strip away society’s polite veneer, revealing hypocrisy, corruption, and depravity just beneath. That is to say, Rodrigues pissed off a lot of people, in particular the Church’s bishops, and many of his works suffered censorship and critical vituperation. As the world has recently seen club-wielding, pepper-spraying cops assaulting peaceful protesters across the United States, it seems fitting that Padilha’s first project for Hollywood is slated to be a remake of RoboCop [Editor’s note: whose script was at the time of this writing in development]. Maybe a Padilha-style beating will also be good for American cinema.

Shari Kizirian is based in Rio de Janeiro.