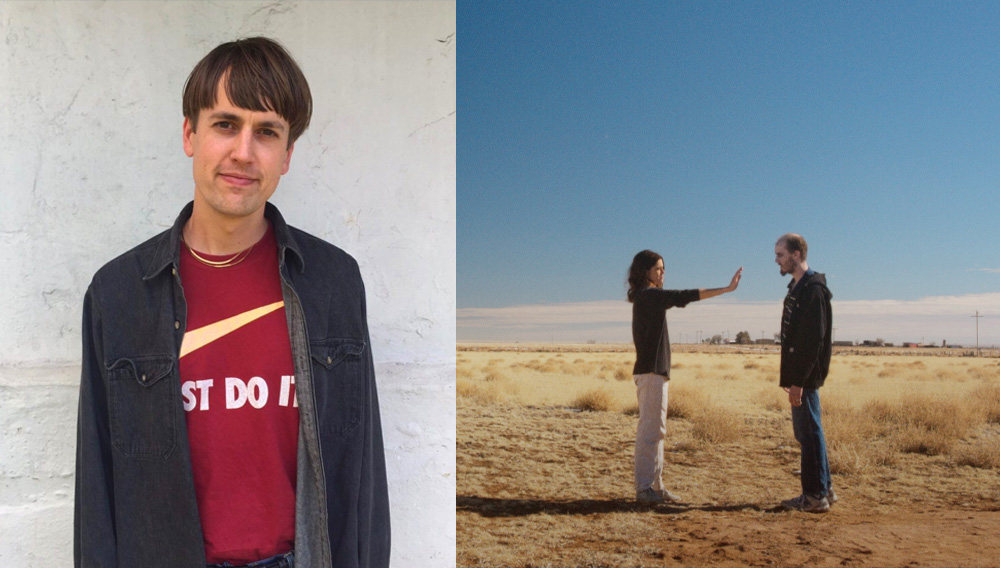

Beyond a doubt one of the year’s most original indie films—DIY or otherwise—the offbeat thriller-slash-supernatural-comedy-of-sorts Jethica savvily snatches the rug out from under all kinds of genre tropes in its brief (yet oh-so-chill) 70 minutes, as a young woman named Elena (Callie Hernandez) comes to the rescue of her old friend Jessica (Ashley Denise Robinson) with a highly irregular stalker problem. The toxic pursuer (Will Madden as “Kevin”) has some issues of his own, which complicate the situation far beyond his deathless obsession with Jessica or the lisp hinted at in the title. Luckily, co-writer/director Pete Ohs thrives on upending convention, and this communal enterprise—which also includes Andy Faulkner as another lost soul—is rooted in an organic process that allowed the production massive creative leeway on a minimal budget.

“My first narrative feature is called Everything Beautiful is Far Away (2017), a sci-fi fable with Julia Garner and a robot head,” explains Ohs, chatting on a recent Zoom call. “I wrote a script. We had $200,000, a 20-ish person crew. It wasn’t necessarily for me, it wasn’t fun.” Since then, Ohs has made his movies the old-fashioned way: As if he were still a teenager. Jethica, which follows the witness-protection comedy Youngstown (2021), reunites the filmmaker with a familiar circle of collaborators, who sought and found inspiration in the wide-open horizons of the New Mexico desert (which, true to his aesthetic, Ohs lensed with his stalwart Canon 5D Mk III camera “with the Magic Lantern RAW hack … Almost all modern cameras are so good that when people are making movies, unless it’s for Netflix, they’re trying to find ways to make it look worse”).

In the following conversation, Ohs unpacks all the creative gamesmanship that made Jethica so spookily fun, to shoot and to watch. “Certified Fresh” on Rotten Tomatoes (93% as of today), the SXSW-vetted film is now streaming exclusively on Fandor, a subversive valentine about romantic delusions and the unexpected prospects of life after love.

KEYFRAME: I gather the whole genesis of Jethica was a bit unusual.

PETE OHS: Yeah, almost every aspect of the film. The core of these movies is to make films the way I made videos when I was 15 with my friends. Let that be the guiding light for all decisions: What would I have done when I was 15? That’s how it ends up being this “trip with friends and a camera.” Jethica started with finding that trailer on AirBnB, just by taking the price slider down as low as you could go.

Why the Southwestern desert? Did you throw a dart at a map?

Andy [Faulkner, who plays “Benny”] had lived in New Mexico for a few years and said, “New Mexico’s beautiful. We should go there.” Pandemic times. Looking for a reason to get out, looking for a story idea that could be done with a small amount of people away from people, because we are already all well-practiced in self-isolation. All of those things fed into what the story eventually became.

The thought that it’s a COVID movie is not the first thing that comes to mind, but peel back a layer and it’s perfectly symbolic of this era.

All four of these characters are isolated and desperate for human connection. That was all of us in 2020.

What other unique traits distinguished this production?

There wasn’t a script. There was an outline for half of the movie. There also wasn’t a crew. It was just me and the actors staying in that trailer for two-and-a-half weeks. We shot the movie chronologically. That’s not that weird. But, you know, a lot of movies aren’t done that way. We would write the scenes the night before or the morning that we were shooting, which I’ve since learned is a very Hong Sang-soo thing, but I hadn’t been aware of him until I had already made these movies.

I heard Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas was shot that way. There may have been a script, but they were rewriting constantly and making it up.

Apparently, Alice in the Cities and Wings of Desire were also made quite loosely without a clearly defined script upon the beginning of production.

How did that work in practice? A nightly jam session with the actors in character?

There was an outline. The night before, I would write a version of the dialogue into the Notes app on my phone. Then I would present that rough dialogue to whichever actors are in the scene and immediately they are saying better versions of those lines. They are pointing out that this line is not necessary, or we should explore this a little bit more and flesh it out. By the end of breakfast, we’d have the finished script that has already been filtered through the actors and writers, which means they already embodied and rehearsed it. It has been internalized by them, which makes the whole process super-efficient.

In traditional filmmaking approaches, there can be so much downtime and disengagement because of moments where you’re not needed at all. What I like about this process is how everyone is very engaged, not just with making the movie, but being alive. There’s a holistic approach to how I think about the experience I’m trying to manifest for myself and these close collaborators, that is to be engaged with your present existence.

Where exactly did you shoot?

The closest gas station was a 30-minute drive. The closest place where the address is listed is Estancia, New Mexico, which is about an hour-and-a-half southeast of Albuquerque.

Just a trailer and literally nothing else?

We were on these people’s ranch and their main house was a half mile away. The little bit of VFX that we did was removing that house from a few of the backgrounds. You could just see it on the horizon. Those were our AirBnB hosts. The other ghost who gets in the ghost fight, that is our AirBnB host. They were really supportive of us being out there. At one point we were like, “Do you want to be in it?” He was down to clown.

How much of the concept was cultivated ahead of the shoot?

I presented this framework of a story. Here’s our location. We have a couple of women, old high school friends, each with their own individual traumas. We have a couple of guys who are not in a good place, one of which is a stalker, and there will be some ghosts. This is the framework that I presented to these actors and then each of them created their characters. It all got passed through me, but for the most part, they would present an idea and often I would just be like: “Great, let’s go that direction.”

Will, I told him, you’re a stalker. He spent a month researching stalkers and said, “I think maybe he has some sort of lisp going on.” He would send me video messages as he was figuring out his character. He would write long letters to Jessica in character to prepare, and then those became scenes. We only had half of an outline for when we went to shoot. As we’re figuring out what the end of the movie is, I’m pitching ideas for what I think it would be. Each actor was very much the overseer of their character. There’s some level playing field where I understand that they have insights into what’s going on, especially for their characters, that are stronger than my own insight.

This may be a DIY production but as it veers into “fantastic” elements, I wondered about aspects like make-up, which must evoke some horror-movie tropes.

The idea of actors playing characters who aren’t alive, doing their own ghost makeup seemed like fun to me. They embraced the idea that part of their process is putting on this makeup. I have a friend, her name is Lauren Wilde, and she is a professional film and television makeup artist. She gave us a little tutorial over Zoom. As we were shooting, the two actors who are playing ghosts … they’re getting better at it. They’re getting more confident, so they’re getting more intense with it. We noticed that the ghost makeup is getting darker now than on a regular movie. I chose to not care. I’m not going to make him wash it off. We’re getting deeper into the mythology of the story world. If the ghosts are becoming more intense, this supports that thesis that their ghostliness is coming out even more.

I also heard that you streamed your editing sessions.

I live-edited on Twitch for probably a month-and-a-half every day. I was just sharing my monitor for 8 to 10 hours. I shared it on Instagram. Filmmaker friends like Jim Cummings, who has a big following, posted a little teaser trailer I made for the Twitch stream, and that probably brought some more attention. I only averaged six viewers a day, but what was really fun is there were three viewers who showed up every day the whole time.

And now they’ve all made films!

I don’t know if they have yet. I feel like they’re on that path. They’re young filmmakers earlier in their careers who are wanting to absorb as much as they can about the filmmaking process. They would ask questions. I would stop and answer them. I felt like they were on my side, that they wanted the film to be good. When they would ask questions or give notes, I took them seriously. I would either explain why I made that decision, or I would hear [them out and] say, “Oh, you’re actually right.” They directly helped the movie be better.

But really the reason I was doing it is—it’s three reasons. One is we are living in the pandemic, so we are all doing Zoom-type things. I had done some editing remotely where the director/ producer is watching the cut through them. I knew that that was possible. And then, too often in the edit part of a film, you disappear. There’s this chunk of time where you just go away. No one knows what you’re doing. I wondered if there’s an opportunity to not have that happen. What if I live-streamed the edit? I thought it had never been done. I couldn’t find anyone that had. You’re literally showing the movie even before it’s good. If I could have watched Paul Thomas Anderson editing Boogie Nights when I was 17, I would have watched that every day. Maybe there’s some 17-year-old Pete out there who would like to see what this looks like? So often the unknown is what stops us, when we think something is more complicated than it might be.