“I went on down to the Audubon Zoo

And they all asked for you

The monkeys asked

The tigers asked

And the elephant asked me too …”

In the 1975 New Orleans funk frolic “They All Ask’d for You,” off the Meters’ classic album “Fiyo on the Bayou,” a zoo full of very inquisitive animals expresses curiosity about an absent guest. The sentiment, however, doesn’t appear to be much shared by the residents of the Salzburg Zoo, featured in the aptly titled Zoo Lock Down (which makes its exclusive streaming premiere on Fandor). The COVID-19 pandemic closed the beloved bestiary in early 2020, isolating its creatures from their human admirers who patronized the site. Aside from limited staff necessary for the care and feeding of the animals, no one was allowed in—except for Austrian filmmaker Andreas Horvath and his small crew.

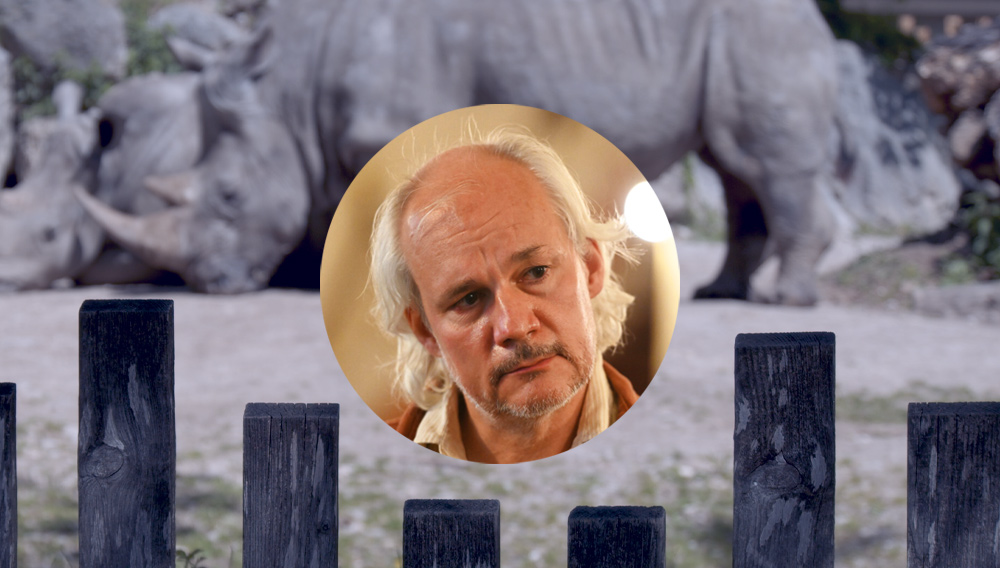

Off and on throughout this odd period of stasis, Horvath documented the behavior of jungle cats, bears, rhinos, monkeys, alpacas, hyperactive lemurs and many more as they returned to a largely unobserved life, free of outside distractions and noise. The film’s mostly wordless flow is at times surreal and absurd, ominous and existential, and nearly always something of a beguiling puzzlement, as Horvath creates narrative tension through skillful editing and suspenseful sound design. So immersive is his camera’s engagement with its subjects that it’s at once a shock and a disappointment when the zoo’s gates reopen and the people return to gawk and marvel.

Keyframe spoke recently with Horvath (now a resident of the Czech Republic) about his experiences in Salzburg, the ideas that shaped his footage, and why he really dislikes zoos!

As a bonus, the filmmaker also talked about the unusual saga of his 2015 documentary Helmut Berger, Actor, a raw and intimate portrait of the onetime muse of Italian master Luchino Visconti—and the legendarily prolific lover of many a 1960s and ’70s celebrity (as in Bianca and Mick)—who died in May at age 78.

KEYFRAME: There has been a glut of “pandemic films” coming out the past couple of years, but this feels original and surprising. What gave you the idea?

ANDREAS HORVATH: I wanted to make a film in 2016 because I heard that the zoo in Buenos Aires was closed after 140 years of existence. I think I saw a photo reportage originally of that. You saw these animals, elephants, whatever, in front of these grandiose stages that they had, like Indian temples. But it closed and the city hadn’t planned for it. These animals were being fed but no visitors came. I wanted to make a film back when the lockdown happened. All of a sudden I had this thought: This would be a good moment to make a film about animals at a zoo that are not being watched.

The irony being that the humans were now in their own cages. Was it difficult to get access?

Not in Salzburg, not at all. I tried in Vienna. I tried in Munich, but it was impossible.

Did the zoo put any restrictions on you?

I work very spontaneously. I like to observe and from the editing, the film comes together. But I could not move as freely as I would have liked. It was a few weeks of shooting. One day with the monkeys and the next day with the rhinoceros. Then I said, I want to see the rhinoceros again. So, it was a few weeks of that and there were also reshoots because we had another lockdown in December later that year, and another reshoot the following year. Also, there were certain things like the shearing of the alpacas. I missed that the first time around. Oh my god, they look so different. What happened?

The rhinoceros sequences were disturbing. I know it happens every day in animal husbandry, but seeing a guy with his hand up a rhino’s ass is still intense.

I cut it in a way that it’s not clear at the beginning what happened. You think it’s an operation? Maybe. Then the music sets in and you think, oh my god, what’s happening? Is it dying? I didn’t mean for it to be unsettling. It’s edited in a filmic way and then it resolves itself.

Your post-production craft creates these small dramas and commentaries throughout that are so much fun—and playfully skewed—that keep you guessing.

You have to keep the viewer engaged, right? Because it’s a film where nothing happens. That’s it. Nothing happens. That’s what the film is about. Everything is created in the editing, which took two years. The sound design and the music occupied me for two years.

Tell us about how you created the music to shape the various odd, incidental moments into something like a narrative.

There are a few musical pieces, but most of it is sound design and you have the idea of constant foreboding. Tragedy.It comes from my feeling ambivalent about the zoo in general. My parents dragged me to a zoo—to this one in Salzburg, actually—when I was maybe three or four years old. I remember very distinctly not liking it back then. It felt awful. Indiscreet—to view the animals which are presented like actors on a stage, but they’re not actors, they’re just being themselves. And we watched them. It didn’t feel right to me, and I’ve never visited the zoo since. During the lockdown I did, yes.

I recently saw again Demon Seed, by Donald Cammell, and I noticed a lot of similarities. Maybe involuntarily, I tried to create something like science fiction. Stanley Kubrick was asked by a reporter about the end of 2001: A Space Odyssey, the last scene when he enters this neoclassical room. Kubrick said the higher entities put [Keir Dullea’s astronaut David Bowman] in a human zoo to study him. He said it reminded him—this room with the illuminated floor and those French paintings on the floor where nothing seems to match—of us humans creating space for animals at a zoo.

It’s exactly what I noticed with those fake murals, those reliefs on the [zoo] walls. You ask yourself, “Is this made for us humans?” It definitely is. But how do the animals react to it, or what do they think—if they think? The music is a comment on these things, which causes light moments. In general, it’s this feeling of uneasiness or asking: Who is the higher entity? We know so little about animals, about what goes on in the mind of a grasshopper even.

Did you have any favorite critters? The extremely active lemurs were especially entertaining.

You start with the primates because there’s so much to see, so much to interpret. The same goes for those lemurs, they’re always a pleasure to watch. But in the end, I could spend hours with the grasshoppers and just watch them, learn things, see things and be surprised still. I wouldn’t pick a favorite animal.

Has there been any pushback from animal-rights organizations?

No. The zoo is also a safe haven for a lot of animals that are being hunted in Africa. The zoo in Salzburg is a very, very luxurious one. It’s so huge. It’s by this huge mountain range. The bears go up there to sleep in the winter, for example. You can read bad reviews on Google about the zoo because they say “We pay the money and we hardly see any animals.”

You’re probably best known for your documentary about Helmut Berger. How did that movie affect your career? John Waters made it his #1 film of 2015. [In Artforum, Waters wrote: “The rules of documentary access are permanently fractured here when our featured attraction takes off all his clothes on camera, masturbates, and actually ejaculates.”]

Sadly, it hasn’t affected me so much. It wasn’t seen because they sued me. That lasted for a few years. It was other people behind him that talked him into suing me, so I sued them. It was a big thing that kept me for four years in courtrooms. I won all the cases. I’m ready now to bring it out again.

Did you ever speak to him about it later?

We made up. Now he’s dead. But two years ago, I was in Salzburg and it was his birthday. I brought perfume which I knew he liked to the reception [in a home for the elderly]. I did not get back home and he had called already and said come over. We spent hours on the terrace of his apartment talking as if nothing ever happened.

Before we go, do you have a favorite production anecdote from the zoo?

Maybe the scene of the piranhas. [A zoo worker wades into the piranha pool, that favored water feature of James Bond villains, yet comes away with his flesh intact.]

Like most people probably when they watch the film, I think, “Oh my god, he’s not going to go in there, is he?” I said, “How do you prepare?” He said, “It’s not a problem. They’re usually not aggressive. I mean, maybe you shouldn’t wear anything red.” Then he comes out in this red swimming suit.