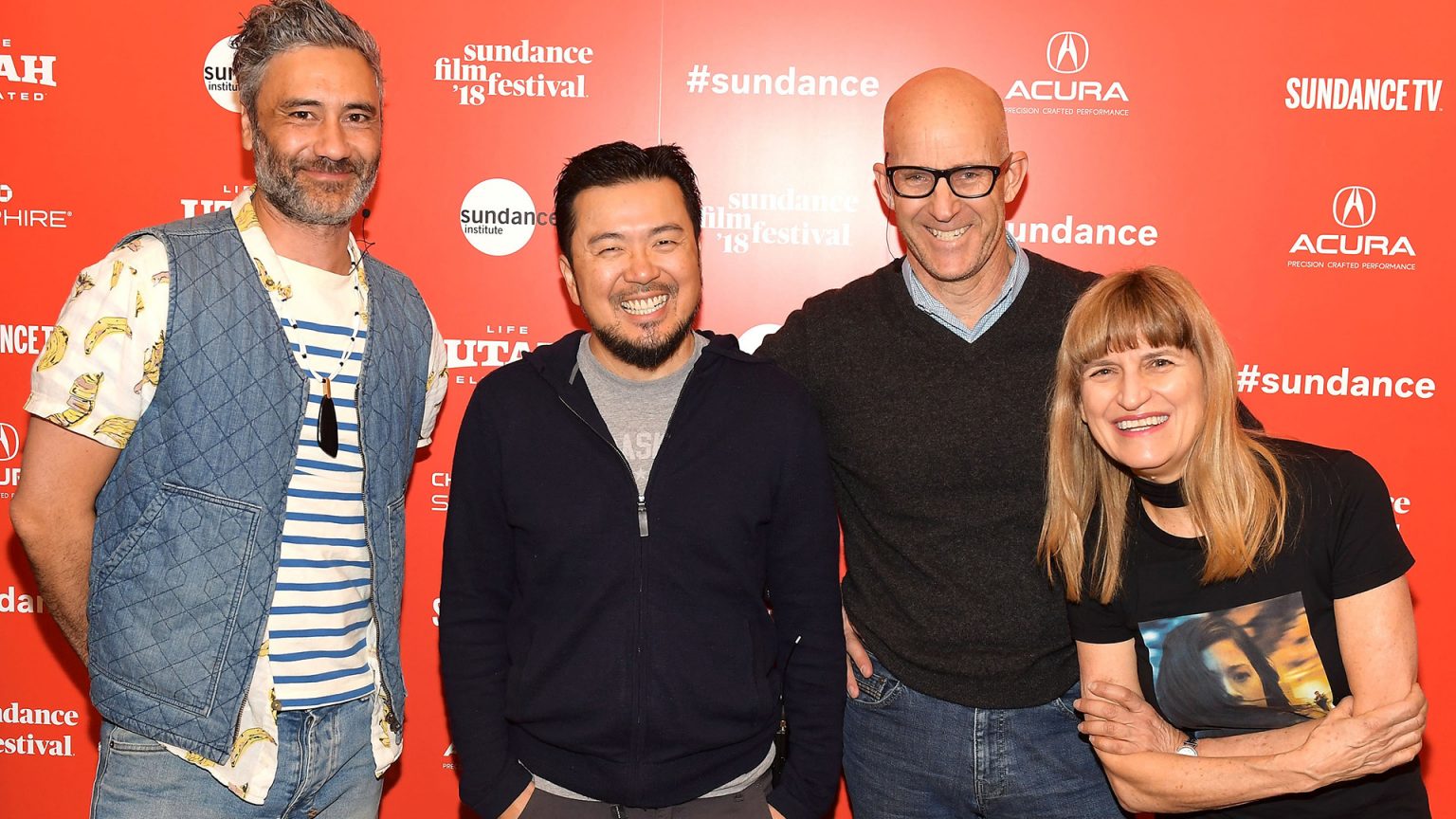

When a director manages to make a great movie with a small budget, one of the first questions a fan asks themselves is, “What could they do with more resources?” At this past Sundance Film Festival, we had the chance to listen in on a panel where directors Catherine Hardwicke (Thirteen, Twilight), Justin Lin (Better Luck Tomorrow, Star Trek: Beyond), and Taika Waititi (Eagle vs Shark, Thor: Ragnarok) shared their experiences of what it’s like going from making indie films to mega-budget summer blockbusters. What does this kind of career leap mean to them creatively, professionally, and personally? The panel was led by John Horn, host of KPCC’s The Frame.

John Horn: Justin, your film was the first of all the panelists to play here. It was Better Luck Tomorrow in 2002. What are your memories of bringing your film for the first time to Sundance? What do you recall about that day?

Justin Lin: Cluelessness, I think. Better Luck Tomorrow was true in the sense that it was a $250,000 credit card movie. We were barely able to even come out here.

JH: Something happened during the third screening of the movie. During a Q&A somebody started attacking you for the way you were depicting Asian-Americans. Someone from the audience gave this person a smackdown. Who was that person and how important was that for the film?

JL: It was Roger Ebert and it was the last question of the night. It kind of framed everything for the discourse [that followed] and made all the difference. I remember we were trying to clear out the theater for the screening and nobody would leave. It was this moment when you feel this energy. People who had very different points of view were able to express it in a very loud manner, I think.

JH: Catherine, what about bringing out Thirteen here in 2003?

Catherine Hardwicke: I remember sitting in a lab on New Year’s Eve and Christmas Eve trying to pull it together. All I was thinking about was bringing it here on time. I just wanted to finish the movie. I was dazzled when it was screened here. I felt this huge energy. We had tried to sell it to Fox Searchlight and get them to finance the movie, but they said, “No, you have to finish it on your own, and if we like it, we’ll buy it.” And I got the call from them that night. They liked it. But first, we had to find the money another way and finish it.

JH: Taika, what about Eagle vs. Shark in 2007?

Taika Waititi: It was amazing and it was in a theater right here. At night it was a smelly and sweaty room. It was already picked up so I didn’t have this stress if someone would buy this thing. And it had a distribution in America, and 17 people have seen it.

JH: How did going from an independent film to a studio film happen?

JL: As a filmmaker, I always want to have context and perspective. I went to UCLA and it was a great experience, but literally within a month, thanks to Sundance, it was going from no one returning the calls to getting hundreds of calls every day. Even before the film was done, Universal called and told me to take over Fast and Furious. I said, “Okay,” because I just wanted to learn. At school, we sat and talked and there were people saying, “I would never make Mighty Duck 6!” And I was like, “Do you even have a chance to make it?” For me, it was just figuring out what I wanted to do and how it works. With the credit card movie, it was just passion and a story you wanted to tell. But very quickly you hit the commerce of it: we couldn’t get funding, then distribution, and then exhibition. I was very young and I didn’t understand it. I just wanted to get a better handle on that. And that’s been my journey for the last 15 years.

JH: Catherine, you went from Thirteen to Lords of Dogtown, and then to Twilight. How would you describe that graduation? How did that biggest step come about?

CH: It was a little different because I had been working as a production designer for studio films, like Vanilla Sky and Three Kings. So I was familiar with the studio politics. I was a little more prepared to be launched into this very supportive atmosphere with Amy Pascal producing Lords of Dogtown at Sony. I was living in Dogtown. They had seen Thirteen and recommended I to do that. It was a natural fit because it was a rough-and-tumble film. The scaling up wasn’t that difficult at that time. As I got more involved in studio politics — that was an interesting thing to navigate: How to keep your voice and be visionary and powerful. It was a good challenge.

JH: Taika, you have Eagle vs. Shark, then Boy, and then What We Do in the Shadows, then you have Hunt for the Wilderpeople. But Thor comes your way before Hunt for the Wilderpeople is released.

TW: I found a good life hack that you edit your [own] movies. I don’t know why no one is doing that. And then I got a phone call that everyone’s given up and they have no one for Thor. It was never a part of my plan. I thought I was going to make four small New Zealand films instead of a big studio film. But when you get this kind of proposition, you think how many children you have and how big a mortgage you have to pay (laughs). But I’ve always liked comic books and thought of making a movie someday. My biggest fear was that I’ve had creative control over my films and with a studio film they’re going to take it away from me. I felt very comfortable making my films. But I thought it would be a good learning experience. I would get out of my comfort zone and evolve as a filmmaker.

JH: Justin, would you say Star Trek: Beyond has anything in common with Better Luck Tomorrow? Do you see any ties between those movies?

JL: Actually, a lot more than it would seem. The whole process of that film was like an indie movie. I was ready to do something else, but I got a call from J.J. Abrams in January asking me if I was a Star Trek fan and if I wanted to take over this movie. You have no idea about anything and you’ve got to start to shoot in June. I had three days to come up with the world, themes, and character arcs. The tough part when we started shooting was that we had to build sequences while shooting and rewriting the script. With Better Luck Tomorrow we did have a script, which is a rare thing in Hollywood nowadays. For me, Better Luck Tomorrow was about telling a story, about characters. With Star Trek…we had thousands of people in the UK and Vancouver. They’re trying to interpret what I’m talking about. This is all developed from scratch. I had to fly to the UK and Vancouver to talk about the shots. This was like coming back to the way I worked on Better Luck Tomorrow because we had to engage in a process. I wanted viewers to feel the humanity behind the shots composed. That was the strongest connection to Better Luck Tomorrow.

JH: There’s an expression that some film school teachers use: “Let your budget be your aesthetic,” that if you have a million dollars, you’re going to make a certain kind of film and if you have a hundred million dollars, you’re going to make a certain kind of film. How does the budget dictate aesthetic for you and what does it mean in terms of what you’re able to do and what you’re not able to do given the money that you have?

JL: I don’t know if I totally agree with that. I mean, I feel like you try to tell your story and if you have a hundred million dollar idea… even ten million dollars… then you start asking the questions, how to make it happen. But I think if you let the budget dictate, that’s when you lose your perspective and I think the soul of the film.

CH: In fact, the movie I just did, it’s called Miss Bala with Gina Rodriguez for Sony, the budget was under fifteen, but they told me, “We want this to look like James Bond.” They literally said that. So that’s a two hundred million dollar movie, so, yeah, we know that, but we still want to look like James Bond, so that’s when we started coming up with, okay, let’s do drone shots, let’s have one day of the helicopter to open up the sequence. I agree with you. You have to stretch. You have to push.

JH: Catherine, I want to ask you a little bit about the way that people graduate from Sundance to Hollywood. It seems to be very heavily imbalanced in terms of gender… that for every Colin Trevorrow, David Lowery, Rian Johnson, Gareth Edwards, there’s one Catherine Hardwicke or one Ava DuVernay. Do you think that the way that the studios look at female directors is different from the way that they look at men, and what are the obstacles that women face that men don’t face in terms of taking that next step?

CH: Do we have a couple of hours? [laughter] A couple of weeks? Okay, well, obviously this is the big topic that we’re all talking about and how to break through that unconscious gender bias and imagine that somebody that doesn’t look like us could do it, that women don’t have to be labeled as emotional when they’re passionate, that, actually, emotion is good, and embrace it. So there are so many ways that we’re just trying to fight the fight every day and we know it’s true that they look at it differently because the statistics just keep coming in and keep pounding us. But we’re optimistic. I think that things are trying to change… Patty, Ava, everybody, every new breakthrough, hopefully, we’ll break through more things. I know the reason I got hired on the movie that I just did, it’s because they probably thought it’s not going to look too good if we don’t hire a woman in this climate. Whatever, we’ll take any incentive to get hired. Guilt, shame, whatever [laughter, applause]. Diversity, inclusion!

JH: When you’re making a non-studio film, part of the challenge and part of the reward is finding people who will believe in you, to finance your film, get it into a festival, getting it a distribution deal. Those are all the necessary steps to making an independent film and none of those are really present when you’re making a studio film. It’s kind of reverse-engineered: this is your release date, this is when it’s going to come out, these are the terms, this is how much money you’re going to get. Does that change the satisfaction of doing the job? That when you’re making a Sundance movie, the challenge is to get it seen by people, and when you’re making a studio film, it’s dealing with the whole machinery and the politics of the studio?

CH: Well, actually, sometimes I’ve been called by the studio and I have to sell them their project; they have the material, and then I have to sell it to them, and I think that’s kind of common. You have to pitch it. They have to be sure they like your vision. You have to do a lot of work to get them to want to make their own movie that they hired you to do.

JH: Is that true?

TW: Yeah, but also, I’m not like some people who bristle at the idea of working with a studio. I’m very easy to work with. And also, it’s their source material… I’m not going to tell them, “You know, this is my vision for, like, your character and this is what I think you should do.”

JL: I think I’ve learned you’re always dealing with human beings. When you do the indie, you feel the pressure but everybody signed up for the right reason and you’re on this journey together. Hopefully, you get a distribution deal and people get to see it. On these big-budget movies, they call it a tent pole for a reason — usually half a billion dollars — sitting on that, you can feel that pressure. For me, it was learning about the humanity behind it.

JH: One of the things I’m curious about is how you prevent the tail from wagging the dog. You are all working with franchises, with Star Trek, Fast and Furious, Twilight, and Thor, and Marvel. And they have agendas. It’s like, we have books, we have merchandise, we have plush toys, we have marketing materials. Pillowcases with Robb Pattinson’s face on it. So how do you make sure that you are within the framework that is going to satisfy what the studio or the financiers want and also make a movie that can stand on its own and has some of your own voice in it?

TW: Well, for me, coming into the third film, I felt very unsure. I said the only way I can really make this work for me is if I can try to make this feel like a standalone thing. If I wanted to do a good service to Thor and to the franchise, I had to concentrate on making it one of my films more than anything, because otherwise I just wouldn’t be happy.

JH: Catherine, what about you? Ultimately, nobody had any idea how big Twilight was going to become.

CH: Well, ours was really different, because ours was the first one and Twilight had been rejected by all the other studios so actually nobody thought it was going to make money so they kept a very tight budget for it and every time I’d go back and say, “Hey, there’s a fan base, you know, and they want to see this scene,” they’d go, “There are just three hundred girls in Salt Lake City that are the whole fan base for Twilight.” So they kept saying “No.” And I’m like, “I think there are more than three hundred girls in Salt Lake City.”

TW: That’s amazing because they listen to the fans so much now.

CH: You know the weekend before it opened, they said, “If it opens at the thirty million we’re going to be excited.” And it opened to sixty-nine million. So nobody actually understood what it was going to do. And so I was lucky for that reason. I could make it more like an indie film and it was the first one. I could cast Kristen and Robb. So I had a different experience than these guys.

JH: We talked about the department heads that you work with when you’re starting out. What about the actors that you worked with when starting out, and how much you want to bring them along with you, and what became of the actors that were in Better Luck Tomorrow?

JL: John Cho is one, Sung Hang. It was interesting, because, after working on Better Luck Tomorrow, I went and I did a studio film that – I mean they’re as talented, if not more talented, than a lot of people I’m working with. And so it became very clear that it was an issue of opportunity. And so to be able to go in there and say, “Hey, I want to cast them,” it didn’t favor or anything like that. They were talented and deserved to be on screen. And, look, it’s been fifteen years and it was a lot harder back then. They weren’t casting Asian people unless they knew kung fu or something. It’s weird now that they’re actually like, “Oh, we gotta go more diverse” and you’re like, “I know.”

JH: Catherine, what about you and the people you’ve worked with in your early films?

CH: Well, you know Nikki Reed from Thirteen, I’ve been bringing her along and so that’s kind of cool. As often as you can, if it’s the right role, I love to work with people that did me a solid early on when I needed the help.

TW: I’ve always used a little handful of people that I always use in my films. And also it makes me more comfortable because there’s a shorthand when you’re working with them. All my friends, growing up making films, there’s a shorthand.

JH: Was there a scene, a moment, something that you really had to go to bat for, that you lost, in making a studio film, that you might’ve been able to preserve if you were making a film on your own?

TW: There was a scene that I wanted in [Thor: Ragnorak], which in hindsight has no business being in the movie. It’s a good thing that they shut it down, but there was a flashback to Thor and Loki as kids, and it was going to be like an ’80s version of Asgard, where everyone had mallets and massive shoulder pads and stuff. And, yeah, I mean, it was dumb, but I felt very passionate about it in the story room.

CH: That’s pretty awesome. I’d like to see that, I won’t see that. The things that I wanted to do for Twilight or any of my studio movies — I got shut down because of the budget. So I never got to do the scenes or the effects that I wanted to do.

JL: I haven’t had that experience. I feel like it’s part of the process. If you work with the right people, you learn how to fight the right way, and I think when people are passionate everybody’s trying to make that happen. But if you really believe in something, you gotta go in there.

JH: This is my last question, are the satisfactions and rewards of making a big-budget movie fundamentally different from making a smaller independent film, and if so, how would you define the differences?

JL: It shouldn’t be. I think, when I first started the switch I thought indie is my heart. It’s my soul. I still love it, but I think I want to transfer that over, even if it’s a pilot, you want everybody to be proud of it, even in failure, you want to be proud of it.

CH: Well, for me, Thirteen was a more incredible experience, in a way, than anything else, because we got invited to film festivals all over the world. So I picked every country that I’ve never been to, and, I’ll go to that, I’ll go to Greece, I’ll go to Rio. And then I told them, “Hey I used to be an architect and a surfer,” and they’d give me a filmmaker that took me to surf in Rio or took me on an architecture tour. You just went deeper by going to all these festivals, meeting all these awesome people, like you guys, that love films. So, that was a better experience for me than just a studio release. I just love that experience of being with other filmmakers.

TW: I think the biggest difference was the scale and, you know, when you made movies for nothing, you just see money burning all around you. Here’s an example. Two weeks before we started shooting, they went, “Taika, we’re gonna give you a director’s tent.” I’m like, “What?” And then, they’re like, “Yeah, so what do you want in it?” I was like, “Guys I’m indie. Indie at heart. Just give me an apple box. I’ll sit next to the camera, I want to be there, with the actors.” Two weeks into the shoot, I’m lying on a chaise lounge. I’m not joking, chaise lounge in my tent, looking at the TV screen with a cheese platter. Yeah, it’s very easy to forget yourself, but I am still indie at heart. I came up to this mountain!

Want more? Watch Boy by Taika Waititi and Sunset Stories, for which Justin Lin served as Executive Producer, right here on Fandor.