In Penny Lane’s The Pain of Others, the human body is a contested territory upon which human and technological sight grind together to reorganize and refute medical “expertise.” Composed predominantly of found footage from the YouTube accounts of three women experiencing Morgellons disease — a skin disease which is regarded as delusional by the medical establishment at large — The Pain of Others uses the illness as a vehicle for bodily exploration and self-discovery.

“There is no such thing as a hypochondriac, only doctors who cannot figure out what is wrong with you.”

-Dodie Bellamy, When the Sick Rule the World, pg. 34

Unable to turn towards medical authorities for guidance, the people we encounter in this film inventively use the technologies at their disposal to give shape and meaning to their illness. Through webcams and twenty-dollar microscopes, they record close examinations of their pores, lesions, excretions, and skin, speaking about their observations directly into the camera. The images produced by these gadgets and technologies facilitate a body exploration, which becomes the launching pad for speculations on political conspiracy, medical conjecture, multiple realities, and aetiological conundrums. The most crucial (and faultiest) technology of them all, however, is the technology of sight. At its most basic level, this is a film that distinguishes the fine line between seeing the same thing in different ways and seeing different things the same way.

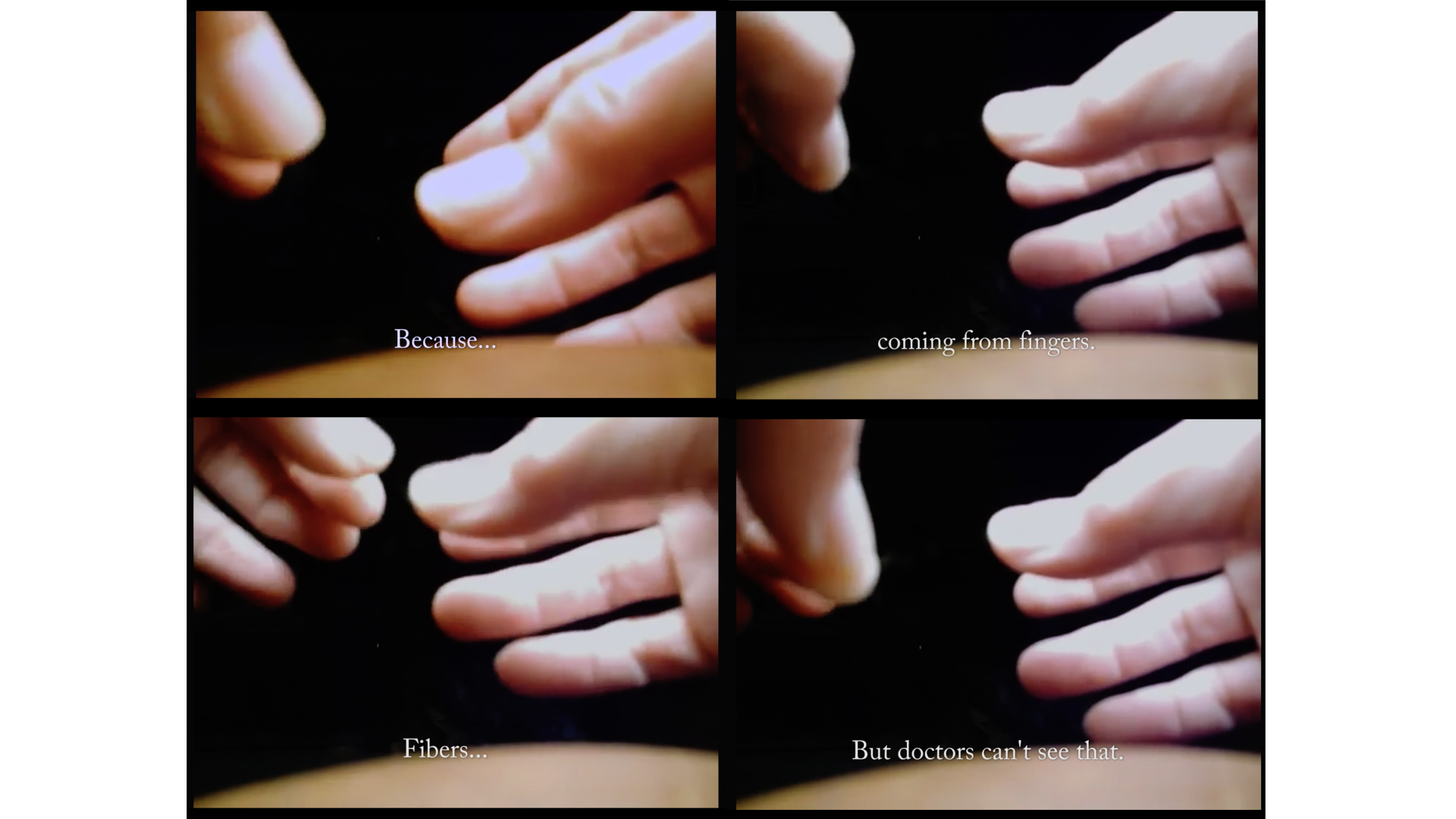

Marcia (@mfromcanada1) holds her fingers up to her webcam. Starkly illuminated by a white light, she lets both hands lightly graze each other. At times, her camera manages to capture the barely illuminated presence of thread-like substances extending between both her hands. As she flicks them or pulls them from her fingers, she speaks to herself: “Fibers, coming from fingers. But doctors can’t see that… I must have a special ability that the doctors don’t have.”

Morgellons disease is characterized by crawling sensations under the skin and the appearance of unusual, string-like fibers on the surface. In this video, as we see the substance being passed between Martha’s hands — whether or not the fiber we see is veritably the product of Morgellons disease seems to be the question at hand. However, perhaps from Marcia’s perspective, the video serves more as a litmus test — a way of determining what kind of eyes are looking at the screen. Marcia’s special ability is a manner of sight that distinguishes her eyes from our eyes or the doctor’s eyes.

Later on, Marcia pulls out a microscope to observe a skin sample that came from her arm. Turning the microscope’s light on and off, she notices how the wire-like matter sitting in the middle of her viewing field begins to twitch, contract, and expand. Enthralled, she exclaims: “Here is a Morgellons machine and it’s moving! Let’s see if it moves again, let’s see if we talk to it”. Without hesitation she begins speaking out various letters of the alphabet, testing the Morgellons machine’s reaction to each letter:

F, F, F…

O, O…

U…A…E

Wow

E, E…

My goodness

I, I, I…

O, O, O

U, U, U

Y, Y

How did you see that! This machine is working! It’s jabbing into things, it’s connecting…

Y, Y, Y,

Why are you moving to the letter Y?

Why are you in my body?

Y/why?, Y/why?, Y/why?, Y/why?, Y/why?”

As outlandish as the gesture of speaking to a skin sample may seem, it is as poignant and direct as an enactment of “communicating with your body” can get. As each “Y” blurs into a “why?”, Marcia can be appreciated as someone who is rigorously engaged in a diagnostic undertaking, endeavoring to understand her skin as a source of vitality, responsiveness, and machination. What is most startling is not the obscenity of her methods, but rather how anchored they are in the hyper-real, photographic, and scientific.

Carrie (@4eyes2sea) also uses a microscope to explore her illness. Moving her cursor around various low-resolution screenshots of pink, craterous skin lesions, she points out the presence of her illness, “Here… look at the Morgellons”.

The illegibility and distortion of each image make it no less captivating. Its glitchy abstraction makes us look more attentively — it brings us closer. If anything, the degree of obfuscation and cloudiness in the image might make the disease more visible. Interference forces us to navigate the possibility of our miss right.

Throughout the rest of the film, the videos we see from Carrie offer a different approach to substantiating her illness. Taking the model of diary-like vlogs, in these videos her face and her expressions are the congealed epicenters of her suffering. As viewers, we look toward the furrowedness of her brow, the wateriness of her eyes, and the puffiness of her cheeks to see the aggregated evidence of her illness.

One such video is uploaded as a response to a comment on her account that mentioned the sadness in her eyes. Staring into the camera intently — breaking focus only to blink — Carrie speaks to this comment: “If you see the sadness in my eyes. It is. It’s really there.”

Perhaps the strangest proposition to be found in the videos that make up this film is not the existence of a mysterious disease, but rather the nature of vision exemplified. The way that visibility is substantiated in this film might be best displayed by the indexical logic of Carrie’s comment: “If you see [it]… It’s really there.”

As troubled, disturbed, and afflicted as the bodies in this film are, there is something powerfully resolute about the steadfast language in which they redefine their illness. Whether or not their ailment is hallucinatory or real, legitimated or un-legitimated, the people we encounter in this film are not passive containers of disease, but rather curious and sensitive explorers of their sickness.

Watch Now: Penny Lane’s found-footage documentary, The Pain of Others, here on Fandor.