Barry Jenkins’ style is distinctive. As we’ve noted before, the Academy Award-winning director is a master of subjective filmmaking — in other words, he has an uncanny ability to put the audience in a character’s shoes. But Jenkins also has a knack for rendering a sense of place, in cities like San Francisco, Miami, and now, with the upcoming release of If Beale Street Could Talk (adapted from James Baldwin’s novel of the same name), Harlem.

Each city has a unique character, but rather than treating these places like characters in a literal sense, Jenkins approaches them with the same specificity with which he writes the characters peopling them.

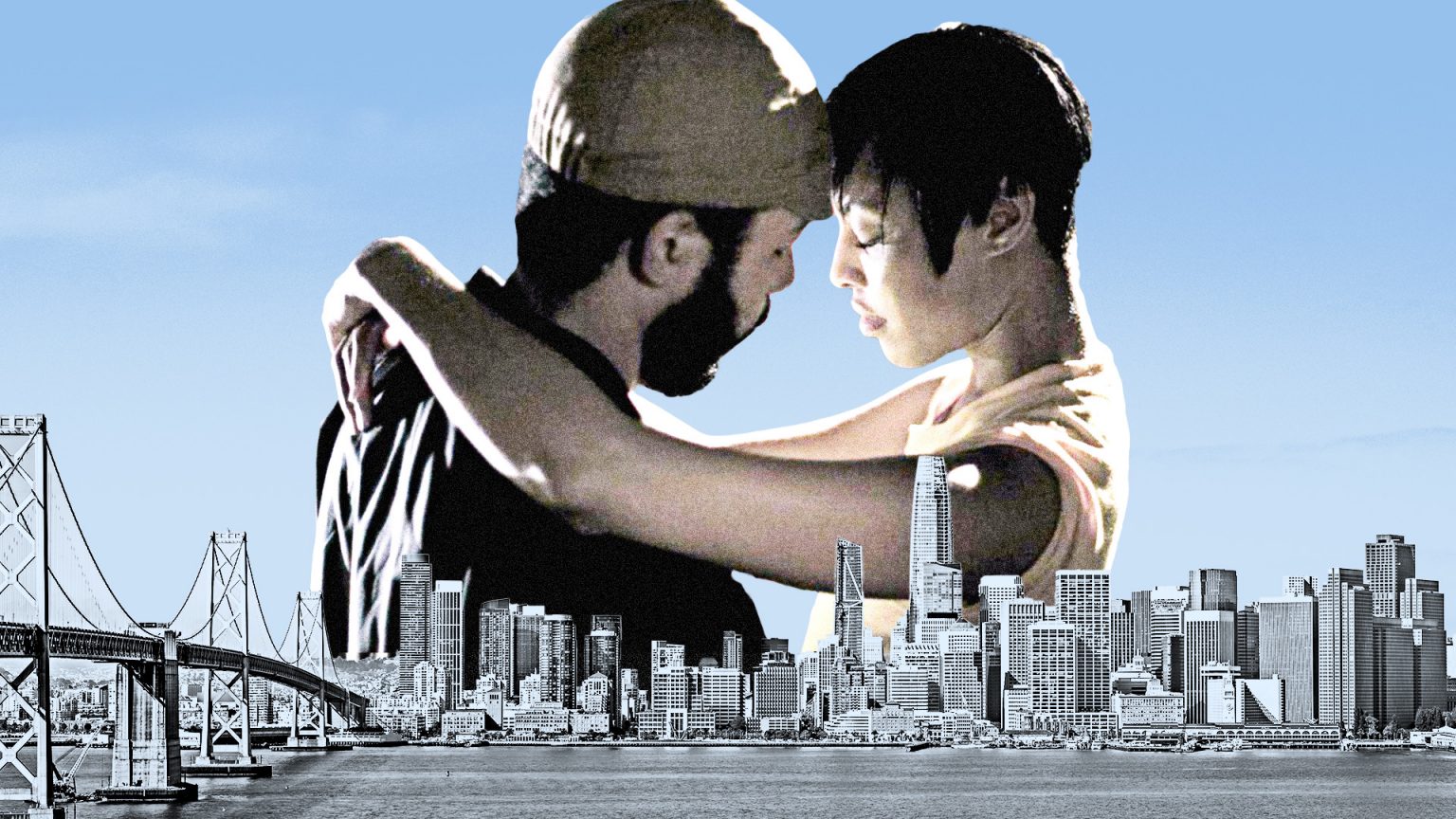

Perhaps Micah (Wyatt Cenac) from Medicine said it best, responding to a question from Jo (Tracey Heggins): “Do you even like it here?” she asks, referring to San Francisco, Micah’s hometown, and the city where Jenkins himself lived for some time. “I hate this city, but I love this city,” Micah responds. “San Francisco’s beautiful, and it’s got nothing to do with privilege. It’s got nothing to do with beatniks or hippies or yuppies. It just is. And you shouldn’t have to be upper middle class to be a part of that.” In this scene, we see Medicine’s thesis made clear — San Francisco is simultaneously beautiful and troubled.

It’s the city whose parks, museums, and clubs played host to a burgeoning if the fleeting romance between Jo and Micah. Jenkins’s depictions of San Francisco suggest a place where intense love is possible — a theme that recurs in the documentary short A Young Couple (2009), which chronicles a relationship between two of Jenkins’s close friends.

Yet, in Medicine and the sci-fi short film Remigration (2011), Jenkins also shows how San Francisco is a city that’s expelling scores of people through an overwhelming wave of gentrification. Regarding issues of race, San Francisco is home to the Museum of the African Diaspora, as seen in Medicine, but it’s also a city where black people only comprise seven percent of the population. A result is a place that cannot be discussed in binary terms.

Ultimately, Medicine’s San Francisco isn’t scathingly criticized as much as it is deliberately evaluated. In this sense, Jenkins is unafraid to illuminate a city’s failings, but he also suggests redemptive qualities. We see this in Moonlight, wherein the city of Miami presents the film’s main character Chiron (played by Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevante Rhodes) with plenty of tough breaks — he experiences a great deal of trauma within Miami’s Liberty City neighborhood. But the city also shields Chiron in a literal sense — as a bullied young boy, he takes shelter in an abandoned apartment. Later, as a teenager, Chiron finds similar repose in empty train cars.

But more significantly, Miami presents a sublime, natural beauty that coincides with meaningful relationships. In gorgeous, cerulean waters, a young Chiron is taught to swim — in more than a literal sense — by Juan (Mahershala Ali), a drug dealer who’s better defined by his kindness than his occupation. On that same beach, Chiron, now a teenager, has his first sexual encounter with his close friend, Kevin (Jharrel Jerome). Ultimately, Chiron leaves Miami for Atlanta, where he becomes a drug dealer himself, but later returns to his home city and reconnects with Kevin. The film ends with Chiron and Kevin sharing an intimate, emotional moment, much as they did years ago on a moonlit beach.

All this suggests that Miami isn’t only a site of deep personal pain for Chiron, but also, a nexus for emotional connectivity and growth. In fact, we see this theme again in the short film Chlorophyl (2011), in which a woman traverses Miami — in all its pastel colors and vibrancy — to forget a strained relationship. The city offers respite to her, as it did with Chiron, and perhaps even Jenkins, who was born in Liberty City, the same neighborhood where he shot Moonlight.

Jenkins’s nuanced portrayals of cities are another of his cinematic calling cards — as distinctive as his close-ups and color palettes — which ultimately communicate authenticity in his filmmaking. These cities aren’t exploited for tragedy, nor are they romanticized like so many cinematic depictions of Los Angeles and New York. Instead, the beauty and pain within Jenkins’s cities conflict with each other — a contradiction that’s only evident to the people living in those places.

As a result, we experience cities like San Francisco and Miami through the same lens as Jo, Micah, and Chiron, which heightens the subjectivity of Jenkins’ signature style. So as Jenkins turns his attention to 1970s Harlem in If Beale Street Could Talk, we imagine that it will be portrayed with the same care and empathy as the places in his previous films. We’ve seen Harlem in film before, but never through the eyes of characters imagined by James Baldwin, and brought to life by Barry Jenkins. We can’t wait.

Watch Now: A Young Couple, Chlorophyll, and more of Barry Jenkins’ short films.