“I had a stupid grin on my face”, Senses of Cinema critic Darren Hughes wrote recently of the films of Jodie Mack, “entranced by the beauty and craft of what I was seeing, and also regretful that my three-year-old daughter wasn’t there to take it all in with me.” There’s a tendency in contemporary criticism, I think, to treat avant-garde cinema as if it ought only to be approached with academic rigor—there’s something about the obscurity of the work that compels critics to theorize it into a sort of willed explication. But Jodie Mack makes short-form avant-garde animations whose most immediate quality is visceral: for all their intellectual depth and thematic richness, they nevertheless remain plainly and unabashedly fun. Avant-garde cinema doesn’t exactly have a reputation for being widely accessible. But the sheer pleasure of experience afforded by something like Mack’s Let Your Light Shine or Glistening Thrills—what Hughes describes as her work’s “rare and infectious vitality”—needn’t be facilitated by special knowledge or scholarly insight. It’s in the nature of spectacle: even a child can enjoy it.

Jodie Mack’s major antecedent in the world of experimental animation is Norman McLaren, the Scottish-born filmmaker whose more than forty years working under the aegis of the National Film Board of Canada yielded collaborations of now legendary repute. McLaren was a theorist of animation as much as he was among its most celebrated practitioners, and, indeed, as critic Bill Schafer notes, he provided the medium with its most widely held working definition: “Animation”, he is quoted as saying, “is not the art of drawings-that-move, but rather the art of movements-that-are-drawn. What happens between each frame is more important than what happens on each frame.” The influence of McLaren’s thought and practice can be felt in everything from the vanguard of experimental cinema, where filmmakers like Mack and her contemporaries continue to advance his working methods decades on, to the world of mainstream animation, where the long-since dwindling classical mode survives largely on the legacy of McLaren’s genius. His style and his sensibility impressed themselves upon the medium indelibly. Even today, twenty-seven years after his death, it’s impossible to imagine the landscape of modern animation without his presence looming over it.

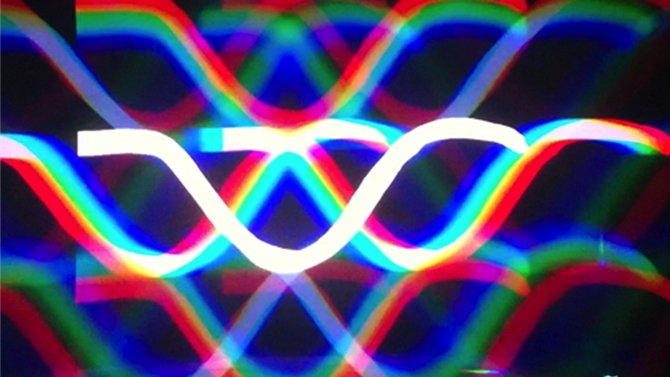

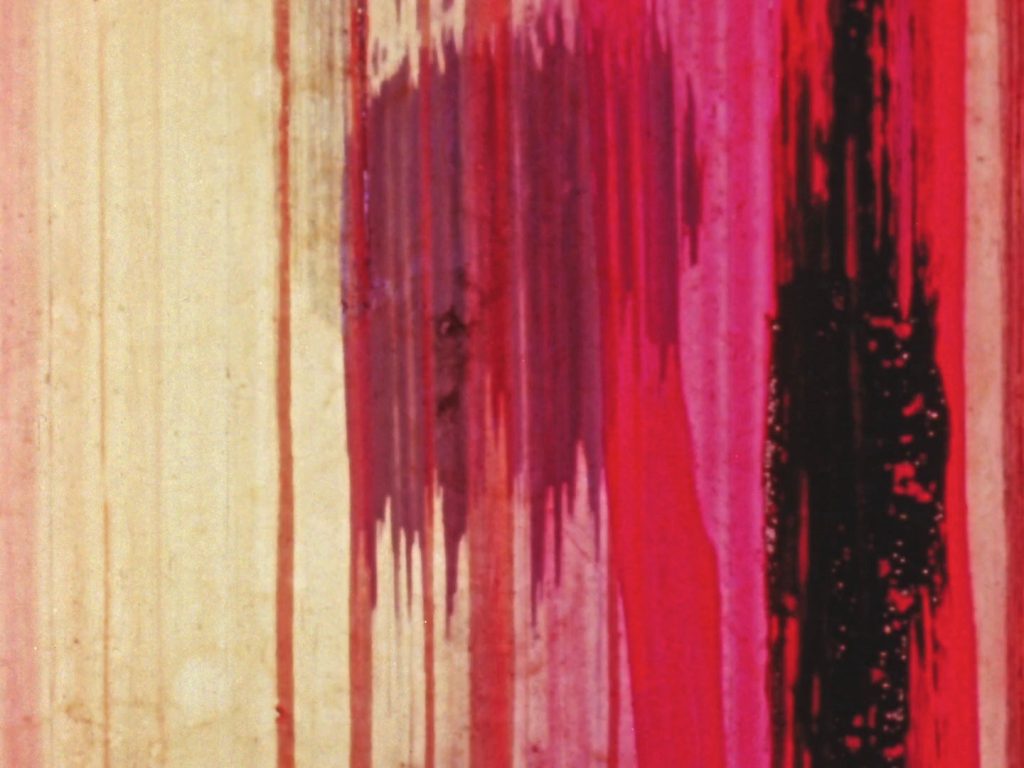

The films of Norman McLaren needn’t be enjoyed theoretically—their vitality, like Mack’s, should be obvious to anyone, from ages three to a hundred. You don’t need to have any understanding or awareness of avant-garde cinema to enjoy his short animations; you hardly need to have seen a film before at all. The first thing that strikes you about McLaren’s eight-minute magnum opus, Begone Dull Care, is not the virtuosity of its construction—though it is of course a masterful exercise in animation technique—but simply its exuberance. McLaren and co-director Evelyn Lambart created Begone Dull Care by scratching and painting directly onto film stock, transforming each celluloid frame into a miniature modernist abstraction; these frames were then arranged in time to the music of Oscar Peterson, whose jazz piano McLaren sought to both reflect and enrich with the image. The result is a work of extraordinary visual rhythm, a symphony of line and color in which nearly every note has its on-screen representation. The only word for it is synesthesiac: we see the music as color and, in a sense, here the color as music. After a while it’s a hard to tell which is informing which.

McLaren and Lambart had to pattern their animation according to the blueprint of Peterson’s jazz—an effort of staggering complexity. In terms of craftsmanship, then, Begone Dull Care is a work of precision: the unwieldy form of painting and scratching needed to be reigned in and controlled, its erratic-looking images marshalled toward an elaborately unified whole. But what’s remarkable about Begone Dull Care is that despite how meticulously it was constructed, the finished product gives off an impression of ease, as if it had been improvised in a sudden flash of inspiration, like jazz itself. Call it a sort of self-effacing exactitude: McLaren and Lambart work hard to make the whole thing look effortless, a thunder bolt of technicolor vigor. We see only the unbridled vivacity, the briskness and dynamism. From the difficulty of the project they have derived a sensation of frictionless joy.

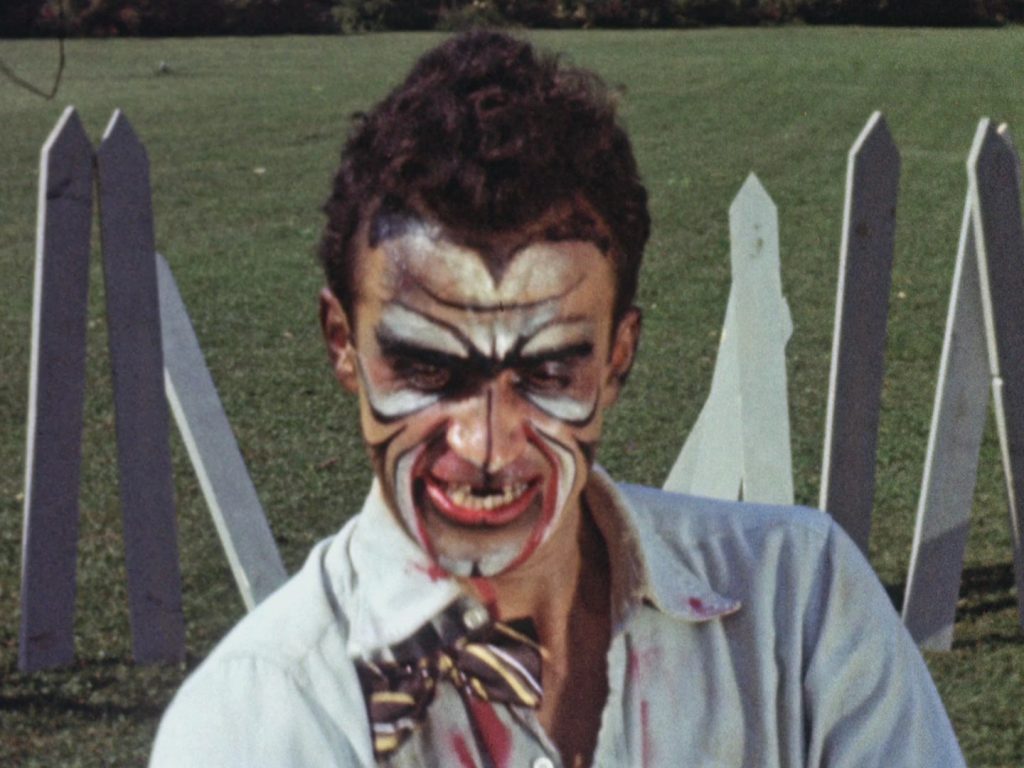

So it is too for McLaren’s best-known picture, Neighbours, which won McLaren international acclaim and no less than an Academy Award. Neighbours is a “live-action animation,” which is to say that it uses a stop-motion photography process in order to create the illusion of movement between real actors and environments. (The movements themselves are stylized by the animation process in such a way as to suggest a kind of unreality, as when a figure slides along the ground or floats through the air.) Though often characterized as an “anti-war film”—it’s even classified as such on its Wikipedia page—Neighbours is hardly a sophisticated political statement, even if it was, in McLaren’s words, inspired by his experience of Maoism and the beginnings of the Korean War. The film’s allegorical dimension, to modern eyes especially, is simplistic almost to the point of seeming quaint: two friendly men fight over a flower which emerges directly between their properties, and in the end their skirmish over the proper ownership proves fatal. It’s difficult to imagine this tract illuminating the virtues of pacifism for anybody, even in the less enlightened days of 1952.

Well, thankfully it needn’t have any merit as a political work at all—such considerations are irrelevant to its simpler pleasures. Though serious avant-garde cinema remains very much the realm of intellectuals and academics, it’s important to remember that the work of the National Film Board has been routinely screened on children’s television networks like TVO, as well as more formally for elementary and high school students in classrooms across Canada, for about as long as the organization has been in operation—indeed, a canonical short like Neighbours is still practically guaranteed a spot in the curriculum of Canadian schoolchildren. A child might not make much of the tenuous connection between Neighbours and encroaching fears of Maoism in the 1950s. But they’ll probably understand that the film has something to do with sharing. More importantly, a child, no less than anyone else, ought to be able to appreciate Neighbours for the marvel of animation that is so obviously is, soaking in its sights and sounds without any concern for its higher aspirations as political cinema. Norman McLaren is the sort of filmmaker whose intellectual substance seems in some sense secondary — though the substance is still very much there — to the plainly qualities of energy, liveliness, and splendor. The films are a joy. Even a child could see it.