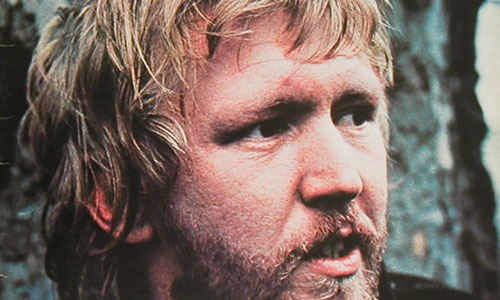

Harry Nilsson grew up in Bushwick, Brooklyn in the 1940s, sometimes eating dog food to scrape by. (“A crummy place to grow up if you’re blond and white,” he later recalled.) By 1971, after a workmanlike period of issuing an album for five consecutive years, he’d accumulated Grammys, wealth, and ubiquity in record stores and on the radio dial. His subsequent career encompassed a very public fall from grace and descent into seemingly irredeemable shabbiness. As shown in Who Is Harry Nilsson and Why Is Everybody Talking About Him?, Nilsson went from clean-cut All-American blond youth (a high school football player, no less) to an increasingly Brando-esque wreck bloated by drugs and booze. But his catalogue comes out in much better shape, even under the scrutiny of present-day perspective.

Watch Who Is Harry Nilsson and Why Is Everybody Talking About Him? on Fandor:

Nilsson entered the music industry as a songwriter, collaborating on three songs with Phil Spector and selling “Without Her” for $10,000. It was a hit for Glen Campbell, a typical irony of Nilsson’s career: his two biggest hits (“Everybody’s Talkin’” and “Without You”) were other people’s songs, and his own songs were most successful covered by others (e.g. Three Dog Night’s version of “One”). That was a guiding tension in Nilsson’s career: the industry wanted him to do the technically immaculate balladeering they could sell easily, while he wanted to prove himself as a songwriter.

Nilsson’s shrewdness and determination to break through to the other side commercially quickly paid dividends: within five years of his first album, 1971’s Nilsson Schmilsson capitalized on the success of “Everybody’s Talkin’,” made ubiquitous by the Oscar-winning Midnight Cowboy. Being associated with the film let Nilsson successfully attach himself to both the envelope-pushing edge of the New Hollywood and radio listeners who liked their songs pretty and string-drenched. Nilsson had submitted an original — ”I Guess The Lord Must Be In New York City” — for contention as the film’s de facto theme. The arrangement — deftly-picked guitars over strings — mimics “Everybody’s Talkin’” precisely, but his cover of someone else’s song was deemed preferable. (It ended up in Sophia Loren’s Lady Liberty.)

The push-pull between golden star voice and under-recognized songwriter became explicit on Schmilsson, which despite its schizoid nature became Nilsson’s biggest seller. Up to that point, he’d produced three albums that basically stayed within the pschedelic post-Sergeant Pepper’s wheelhouse, as well as an album of Randy Newman songs, Nilsson Sings Newman. Schmilsson is a different beast altogether. “Without You,” its biggest hit, was a cover of a song by the perpetually ill-fated Badfinger; Nilsson ditched the original’s rock-groove-cred for maudlin strings and multi-octave wailing.

Yet Schmilsson also had room for (to name only its singles) bizarro novelty song “Coconut” (perhaps the only ditty to appear in both “The Muppet Show” and a Quentin Tarantino movie)

And there’s “Jump Into The Fire,” a hard-rocking proto-Krautrock 7-minute jam way ahead of 1971’s mainstream musical landscape. (No wonder LCD Soundsystem covered it during their last show: like Nilsson, LCD mastermind James Murphy is another adept musical pastiche scholar simultaneously seduced by and driven to desecrate popular song forms.)

Nilsson’s collaborator for Schmilsson was Richard Perry, one of the most successful producers of the seventies. In the documentary, Perry talks with disarming frankness of his initial certainty that he’d continue working with Nilsson through the seventies, taking over the commercial world one hit at a time. Nilsson, however, was having no part of it: Perry went on to shape hits for the likes of Carly Simon and Leo Sayer, edgeless AM radio company alongside whom Nilsson wouldn’t have stood comfortably.

What Perry and the industry at large valued was Nilsson’s voice, a multi-octave beast he could use to multi-track his own back-up choir. Nilsson appreciated his technical gift as well: he recorded 1973’s otherwise inexplicable standards album A Touch of Schmilsson in the Night to capture his voice at its peak. But, at heart, Nilsson was a studio nerd: 1972’s Son of Schmilsson has a funny skit about a vampire menacing a man with the help of RCA’s library of sound effects.

Nilsson’s post-Schmilsson years generally horrified the industry: not because of all the partying, but because he destroyed his voice while recording 1974’s Pussy Cats. Rather than letting producer John Lennon know he’d ruptured a vocal chord, he added another layer of perversity to an already plenty bizarre record, singing scratchily in an affront to an industry that prided clear, angelic vocals over all else, but an inspiration for later bands. (The Walkmen re-recorded the album track-for-track in 2006; it took the music industry about 30 years to catch up.) Before retiring from producing albums in 1980 to concentrate on advocating for gun control, Nilsson recorded even more unmarketable albums: in many ways destroying his biggest asset made the vocals as odd as the sensibility behind the songs.

But to hear late-period Nilsson eccentricity at its most arresting, consider “It’s A Jungle Out There” from 1975’s Duet On Mon Dei. The documentary shows that the recording sessions were basically an excuse to get coked up on the record company’s dime, and it shows, but Nilsson never sounded looser (Pussy Cats, with its string overdubs and nightmarish horns, sounds determinedly rather than authentically ragged). “It’s A Jungle” has no guitars: the melody’s in the bass line and horns, with Nilsson striding through the song like a champ, comfortable in his dissoluteness. It’s uber-of-its-time, or maybe five years ahead of schedule (about as far ahead as Nilsson could get): it sounds like the theme song for a grimy seventies sitcom, and it swings.

Nilsson’s recording career lasted fifteen years, during which time he went from psychedelic paisley type to a comfortable wreck. His cult appeal is thanks to both sides: the smooth pro and the risk-taking degenerate, a transition few people manage with any grace.