The original Jurassic Park film was released twenty-five years ago this June and has remained as resonant and watchable as ever. At its core, Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film was not only a monster movie but a morality tale about greed in all of its manifestations. In the film, innocent people pay the price for the InGen corporation’s malfeasance, and childlike marveling quickly becomes a terrifying nightmare. Unlike its sequels, the original film contains uneasy tensions between the beautiful and the ugly; it’s in this spectrum of human behavior that leads to humanity’s greatest discoveries and its greatest crimes. When wielded recklessly, technological and scientific progress bring hidden monsters to life, and while some may be harmless or even beautiful, others are dangerous—all teeth, claws, and otherworldly roars. “Life finds a way,” as Ian Malcolm (Jeff Goldblum) is wont to say, but so does greed and selfishness.

Before the carnage begins, the film takes time to bask in the marvel of seeing prehistoric animals in their tropical surroundings. Paleontologists Dr. Sattler (Laura Dern) and Dr. Grant (Sam Neill) are overcome by the living, breathing dinosaurs, which they had only studied from afar, across the void of time. Here, the film is bright and hopeful, buoyed by John Williams’ emotional score. To underline these feelings of awe, Spielberg often shows us the expressions on the character’s faces before showing us what they see. The first encounter with the Brachiosaurus is framed through their responses: Grant tears off his sunglasses to reveal widened eyes and Sattler follows suit, her jaw-dropping. But awe turns out to be a misleading emotion. It can be bottled and sold. Its pureness can be blinding, misdirecting our gaze.

The tone of the film shifts quickly as the initial wonderment is replaced by feelings of unease about the reality of prehistoric creatures roaming the island. Seated in a dark room, lit ominously with cameras projecting data visualizations and charts marching optimistically upward, Malcolm, Sattler, and Grant voice concerns about the park. Hammond (Richard Attenborough) opines: “How can we stand in the light of discovery and not act?” But his impassioned musings are undermined by the visual messages all around him. Hammond is motivated by more than just scientific progress. His ongoing refrain: “Spared no expense!” is a constant reminder of how much he has invested in the park.

In fact, from the first frames of the film, it’s obvious that the park values its assets above all else, including human life. The film opens with the death of an anonymous worker, whose attack sets off the investigation that puts the narrative into motion. Muldoon (Bob Peck) holds onto the man, begging someone to shoot the attacking Velociraptor before it’s too late. From there, the specter of the InGen Corporation continues to loom over the film. The Jurassic Park branding is constantly visible, slapped on the sides of Jeeps and gateways, embroidered on uniforms. In addition to being scientific marvels, big dinosaurs are big business.

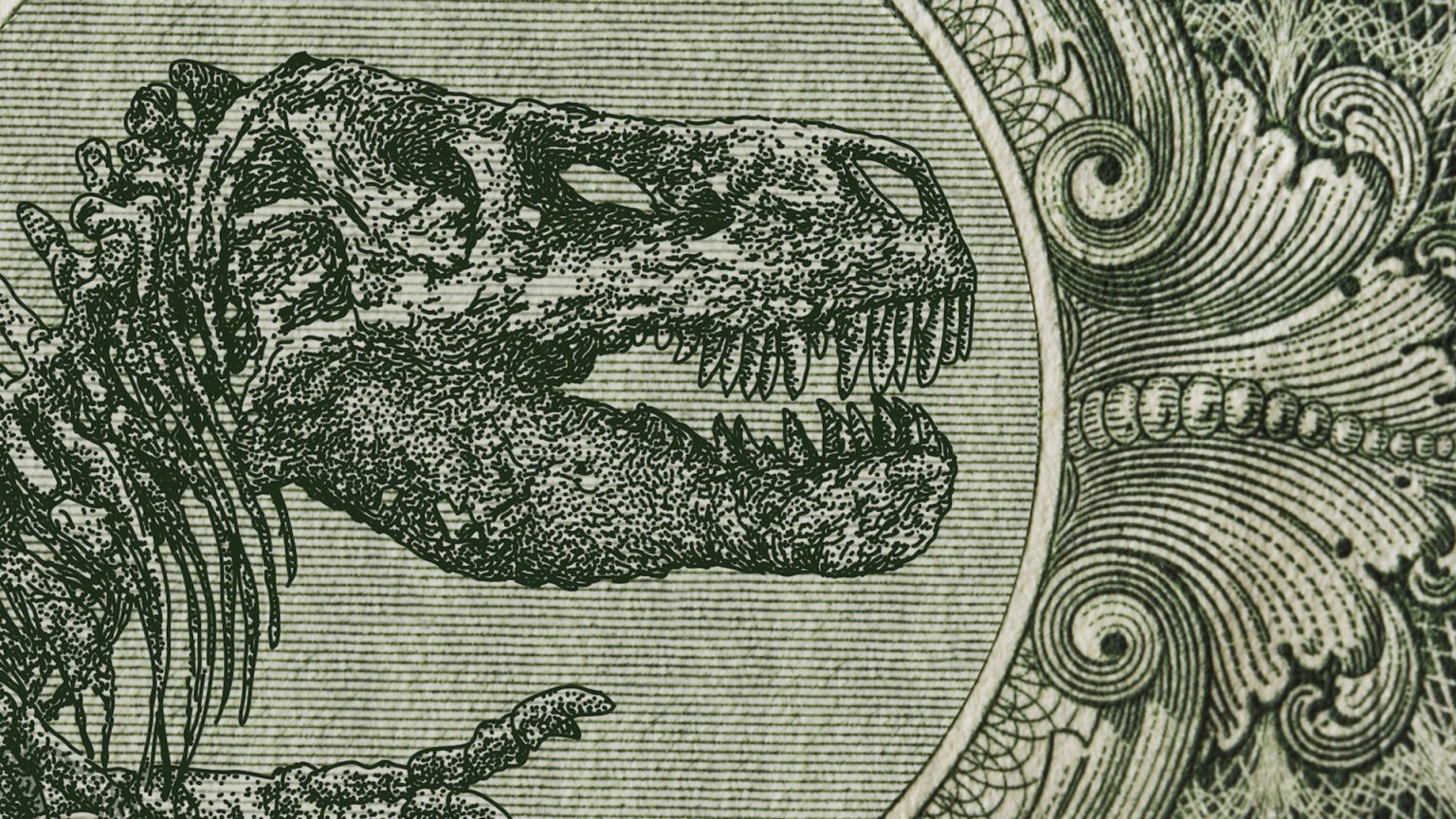

Of course, the facade soon crumbles. The meticulously designed trappings of the park come crashing down, and the visitors are reduced to prey, rain-drenched and running for their lives through the night. Once again, Spielberg focuses on the characters’ reactions and mounting fear, but this time around, the awe has been replaced with pure terror. When the Tyrannosaurus approaches, the passengers feel it, rather than see it, coming. In one of the film’s most iconic scenes, Timmy (Joseph Mazzello) looks on in concern as the impact of something enormous causes the water in the glasses to quake, creating a ripple effect. The visitors are no longer looking from a safe distance, but have become unwitting participants in the action—locked in the gaze of predators on the hunt. Another classic moment hammers this point home: The Tyrannosaurus roars, and a banner reading “when dinosaurs ruled the earth” falls down around her neck. She looks like a triumphant athlete, draping a flag over her shoulders. The marketing promising an exciting place to view prehistoric wonders collides with the reality that the park has become a deathtrap, and the animals have taken control.

Jurassic Park is just as much about humanity as it is about dinosaurs, and that’s why, no matter how long the franchise continues, people will always return to the original film. Monster movies always serve to remind us of our own animal nature, and Jurassic Park accomplishes this better than most. The urge to make sense of the mysterious is very human, but so is our desire to conquer and exploit—to be first and best. And these qualities often follow directly on the heels of scientific discovery.

Even with all the power that humanity wields, even to resurrect long-extinct species, we are still living creatures that could die at any moment. We feel terror, we perceive beauty. And so that is, inevitably, what the film leaves us with, but it is a return to the beauty of the familiar, of our own time. As the InGen-branded helicopter whisks the survivors into the sunset, Grant looks out the window to see a flock of pelicans winging over the ocean—living vestiges of dinosaurs with which we already share the planet. The world around us is a constant inspiration, full of mysteries. Among these are our own monsters, which we continue to grapple with.