The heart of the genius jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman came to sudden stop yesterday, June 11th, after eighty-five years of uninterrupted beating. He died as a consequence. And his death was significant enough to place his name on a list it had never been before: trending on Twitter. This is really impressive, if you think about it. Coleman was not a pop star. He made difficult music. He was a difficult artist. His kind usually enter and leave the world without causing much of a stir, like a ghost. But history was not hard on this man. He came into his own at the right place and the right time—a time when jazz needed something new; when it was, though still popular (the late fifties), fast running out of creative steam. The direction that jazz took to get out of its post-bop rut was, on one side, fusion, which was ushered in by Miles Davis. The other was free jazz, which was ushered in by Cecil Taylor, who is still alive, and Coleman.

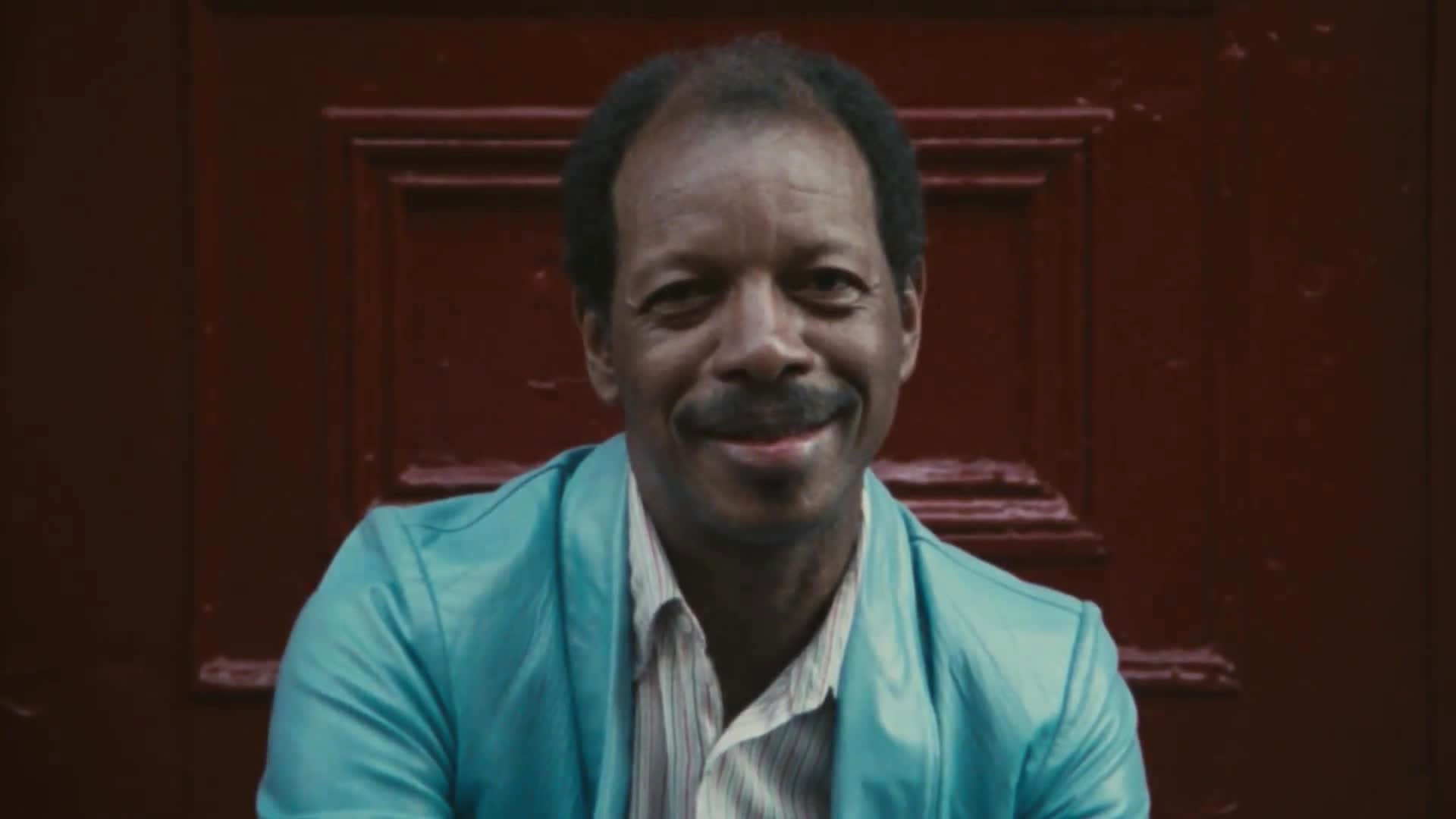

As the jazz journalist/historian A.B. Spellman explained in his sadly forgotten little book Black Music; Four Lives, Cecil Taylor and Coleman had completely different backgrounds. The former came from a black bourgeois family and was trained at the prestigious New England Conservatory. Coleman, on the other hand, came from a desperately poor family in Texas and was self-trained. What we read in Coleman’s life is the true story of a self-made person—he came from nothing, from nowhere, and incredibly changed the world around him. He was, in short, a natural. Writes Spellman: “He was a walking myth, the image of a small bearded man striding out of the woods of Texas and into New York’s usually closed jazz scene.”

Though he walked into this scene at the right moment, everything about him is so improbable. Cecil Taylor’s story is just lovely and neat, just how you want stories to be: he was gifted, he came from a good family, and he had an excellent education. The chaos of Coleman’s formation is very disturbing (a disorder of dots that are very hard to connect), and yet he went on to write one of the most brilliant works of jazz composition, “Lonely Woman,” led the most handsome and hippest quartets of his moment, formed a close relationship with the most elegant and educated black jazz pianists of the 20th century (John Lewis), and his contribution to the score of David Cronenberg‘s brilliant film adaptation of William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch made it even more brilliant.

Let us end this brief note with a curious story Coleman relates in Shirley Clarke’s documentary Ornette: Made in America. He explains that on one sunny day in New York City, he was walking down a street when suddenly a woman unknown to him did the kind of thing that almost only happens in dreams. She kissed him on the mouth romantically. But as if wanting to wake from the dream and check in with reality, he broke the kiss and asked if she knew him. She did not. And with that said, she walked away. Coleman then gets into a thought that’s been deep in his head for a long time. He wonders what would have happened if he had just trusted the dream and let the kiss last? What would have happened to his life if he had just done that? Where would he be now? Goodnight, Ornette Coleman.

Charles Mudede is a Zimbabwean-born cultural critic and film editor for The Stranger. Mudede collaborated with the director Robinson Devor on two films, Police Beat and Zoo, both of which premiered at Sundance–Zoo was screened at Cannes.