“The threat of disaster is never pleasant.”

These words of narration—spoken in a 1959 instructional film called Civil Defense in School—may sound Pollyannaish to our modern ears. But as dry and naïve as most 1950s educational films appear to be, they also depict an archetypal dazed-and-confused moment in American life: not just the Atomic Age, but those fraught years of elementary and high school-age development. While these 16mm instructional films may feel anachronistic and out of touch, they continue to resonate as snapshots of profound anxiety and false security. Growing up isn’t just hard to do; as the recent tragic events at Pennsylvania’s Franklin Regional High School indicate, it’s downright scary.

Civil Defense in School embodies many of the clichés we’ve come to associate with old-school instructional movies. Buzz-cut authoritative-looking men, wearing suits and ties, offer the promise of protection in the face of overwhelming catastrophe, while a fatherly voiceover intones similar platitudes: “The conditions of survival are learned,” he says. “Preparedness becomes a personal responsibility.”

But like Jayne Loader, and Kevin and Pierce Rafferty’s famous found-footage send-up The Atomic Café, with its repeated archival footage of duck-and-cover drills, these films evoke the opposite reading. When, for instance, we see examples of their preparedness—kids practicing first aid by bandaging their fellow students or “young homemakers” learning ways of preparing food for large groups—Civil Defense in School becomes a picture of gross negligence, not responsibility. And as the film ends on a series of close-ups of high school students looking innocently up towards the authoritative camera, we see their guilelessness and vulnerability—a population kept in the dark and ignorant about the cruel ways of the world.

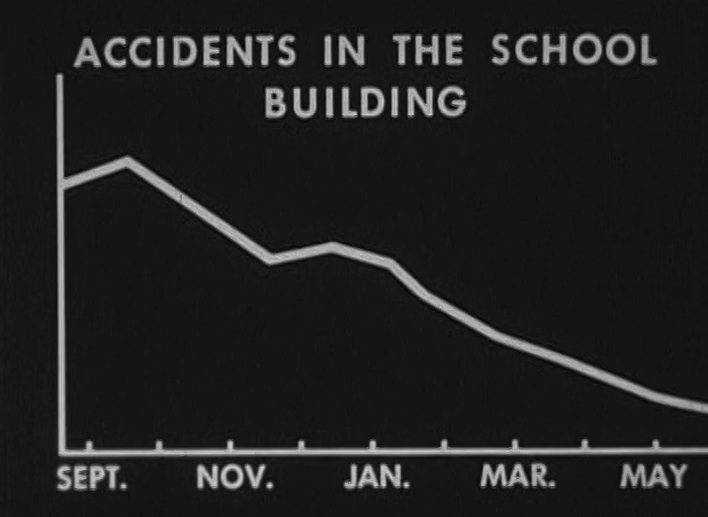

Safe Living at School (1948), produced in consultation with the National Safety Council, treads a similarly strange line between fear and security. The school environment becomes both a host of potential dangers, but also one in which those perils can be managed with the help of a good checklist. Young students Ted and Ruth, with the help of the unseen Voice of Authority narrator, come up with some guidelines for “safe living at school”: 1) “Good housekeeping” (“Uh oh, someone might slip in that spilled water,” 2) “Skillful and correct actions” (at the drinking fountain, “his mouth only touches the water”), and 3) “Courtesy” (“Keep your feet of the aisle or someone trip”). Managing the world’s dangers ultimately comes down to a set of rules, guidelines that delineate the thin line between order and chaos, good and bad.

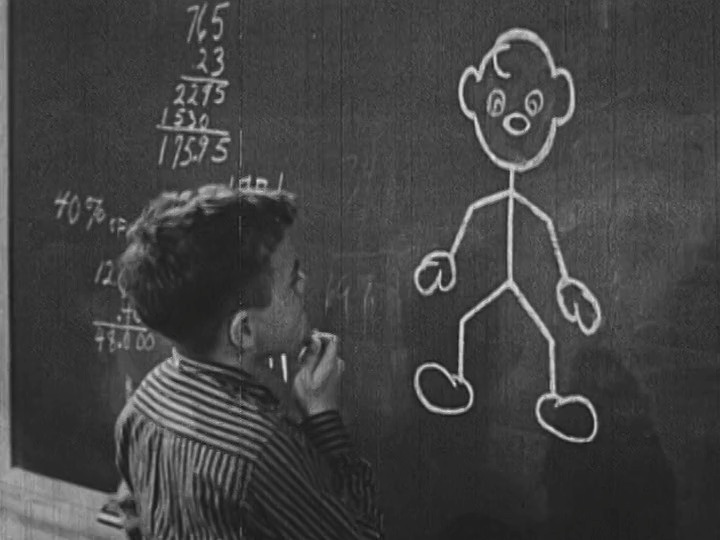

Likewise, in Manners in School, from 1958, a scowling grade-school kid named Larry, who uses an eraser to threaten an animated chalk drawing (“I’m going to wipe you out,” he snarls), learns to follow the “rules of good behavior,” going from abusive bully to obedient child in a few easy steps. (Poor Alice, the target of Larry’s ridicule, downtrodden and sullen, may not turn out as lucky.)

The irony in watching old safety films is the quaintness of the threats and the response to them: Whether the seemingly harmless way Larry antagonizes his fellow classmates, the calm manner in which high school students board buses to escape the reaches of atomic fallout or how elementary-age kids line up in orderly single file and head for the emergency exit in case of a fire, the portrayals don’t correlate with reality, neither then nor now. Imagine an analogous safety video made today, giving instructions on what to do when a heavily armed intruder enters the school and begins shooting or stabbing students.

The prophetically titled, Fears of Children (1951), from the Oklahoma State Department of Public Health, relays a similar array of tribulations that await kids—and their parents. But told as a narrative (rather than a second-person mode, commanding the viewer), the film unfolds more like a psychological thriller, putting us in the perspective of a troubled five-year-old named Paul.

“Put those scissors down, you’ll cut yourself!” yells Paul’s overprotective mother Helen. “You might poke your eye out, baby.” And when the young boy accidentally knocks over his father’s coffee later that morning, the overbearing dad lays into his young son hard, “Now’s that’s it!” he yells. While the anxieties in Fears of Children are more Oedipal than societal, the thirty-minute short shows how the bad behavior of youngsters can turn from innocent to menacing. At one point, accentuated by horror-sounding notes on the soundtrack, little Paul drowns his stuffed bear as a way to rebel against the Law of the Father. “Fears of Children” suggests such actions are natural in the course of childhood development. But that’s not always the case.

Like Civil Defense or Safe Living in School, Fears of Children has larger echoes with the conventions of the horror genre: The films contain repressed anxieties that remain under wraps, ready to burst out and devour the innocents. But all of the films stop short. Instead of letting the calamity-causing demons out, they put them back in the box. The potential perils of protecting our children come immediately with all-too-easy solutions. All Paul’s father has to do to keep his son from turning into a monster is to simply allow the youngster to express his anger without rebuke. It is doubtful anyone would give the same advice to the parents of Franklin Regional High School’s Alex Hribal. (augustafreepress.com)