[Editor’s note: As part of our Fifty Days, Fifty Lists project, the Film 101 series that continues today on Keyframe offers a short alternative course in cinema. By the time it’s completed in five parts over five weeks, you’ll have hit film’s floodlit high points and ventured down its dim back alleys. Notebook optional. For review, check out Film 101: Part One and Film 101: Part Two. For more, see Parts Four and Five, which will be linked when they’re ready.]

A Night in a Dormitory (1930)

Experiments with synchronized sound date back to the earliest days of film. But it wasn’t until Broadway luminary Al Jolson made his feature film debut with 1927’s maudlin part-sound The Jazz Singer that the idea suddenly caught fire. His followup The Singing Fool the next year was an even bigger hit. They triggered a crisis for movie studios (and cinema owners): While everyone wanted to jump on the “All talking! All singing! All dancing!” bandwagon, many hoped this “fad” wouldn’t last, because the technological changeover required was expensive. (And coincided with the beginning of the Great Depression.) It was soon clear silents were no longer golden, however, and “talkies” here to stay, despite their initial clunkiness. That quality is well illustrated by A Night in a Dormitory, one of umpteen movies from the era that pretty much threw musical comedy stage and vaudeville talents onto the screen. This New York-shot short has a couple very chorus-line-ready “college girls” recalling a night on the town, which provides an excuse for several amusingly creaky acts including a comedy duo, a mock “Russian chorus,” and nineteen-year-old Ginger Rogers singing a couple numbers in a high-pitched Betty Boop-style voice. Three years later she’d be a Hollywood up-and-comer fatefully paired with Fred Astaire for the first time. Their classic musicals together would demonstrate how fast and how far the “talkies” had evolved in a short span.

Bimbo’s Initiation (1931)

Famously pioneered by Winsor McCay (1911’s Little Nemo, 1914’s Gertie the Dinosaur), cartoons gradually became a staple of movie programs. Walt Disney’s great success with Mickey Mouse cemented their role as entertainment primarily aimed at children. But his contemporaries the Fleischer Brothers were chief among rivals who often managed to sneak more subversive, grownup ideas into ‘toons, where via the sexy presence of Betty Boop or the use of full-tilt surrealism. Both are on display in this wild ride, in which Betty’s pal Bimbo resists a secret society’s nightmarish “initiation,” which puts him through a series of absurdist perils. The Fleischers also did well with Popeye and Superman’s first animated adventures. But the arrival of 1934’s censorious Production Code and the financial strain caused by their two later features (Gulliver’s Travels, Hoppity Goes to Town) ultimately thwarted their studio’s attempts to compete with the mighty Disney. Faring better was Warner Brothers, whose “Merry Melodies” brought the world Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd and others.

Wings of Youth (1940)

1939 is often called “Movies’ greatest year,” for its extraordinary pileup of classic features from both Hollywood (most famously Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz) and abroad. But that semi-accidental peak occurred under the shadow of global conflict that would drastically impact filmmaking worldwide. World War II would temporarily shut down several industries, while heartier ones found themselves alternating escapist fare with propaganda commissioned by their governments. Here’s an early Canadian screen war effort, outlining the history of Commonwealth air forces while encouraging able viewers to sign up for service. On and offscreen in other nations, the starriest film talents lined up to “do their bit,” whether performing live for troops or making movies emphasizing wartime courage and sacrifice. Leading Hollywood directors went to the Allied combat zones to shoot documentaries, including John Ford (The Battle of Midway, 1942), Frank Capra (The Nazis Strike, 1943) and John Huston (The Battle of San Pietro, 1945).

Scarlet Street (1945)

War documentaries and combat dramas aside, Hollywood’s biggest role during WWII was simply keeping homefront morale high by providing a steady diet of escapist musicals, comedies and adventures. But when the conflict was at last over, returning soldiers and weary civilians alike craved more hard-hitting entertainment that reflected their somewhat disillusioned mood. Thus was born what the French eventually termed “film noir,” an influential cycle of tough, cynical crime dramas notable both for their high style and brute realism. An outstanding early example is this 1945 classic by the great German Jewish director Fritz Lang (Metropolis), who’d fled the Nazi regime for America years earlier but only really found his metier again with these “hard-boiled” postwar melodramas. Scarlet Street has Edward G. Robinson as a nebbish amateur painter toyed with like a mouse by the meaningfully named Kitty (Joan Bennett). Bennett had been a dewy-eyed ingenue in the 1930s; with this role she gleefully re-invented herself as one of noir’s nastiest, trashiest femmes fatales. She’s delightfully partnered here by Dan Duryea’s even sleazier petty-thug boyfriend.

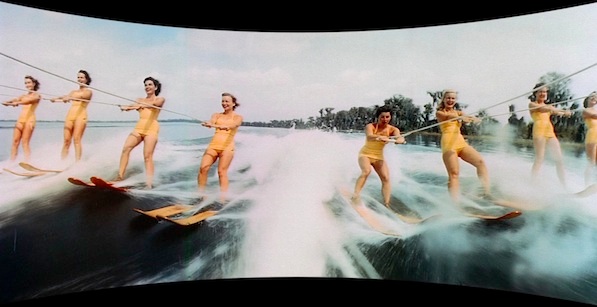

This Is Cinerama (1952)

In the mid-1940s, about two-thirds of all Americans went to the movies an average of once a week. They didn’t even care much what they saw: If they didn’t like the main feature, there was probably a second one, plus a newsreel, cartoon, comedy short, and miscellaneous other attractions on the bill, providing much bang for your buck. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, Hollywood’s worst nightmare arrived in a little box. Television invaded nearly every home in just a few years, dragging down cinema attendance with it. Why pay for entertainment you could now get free in your living room? The industry frantically countered by offering whatever the “boob tube” couldn’t. That meant mostly large-scale spectacle of one sort or another, from the first 3D vogue to “cast of thousands” epics in widescreen formats. The widest of them all was semi-circular Cinerama, billed as “an entirely new medium” that gave viewers “the full wonder of reality.” The extra-large travelogue thrills of This Is Cinerama and its few successors were impressive, all right. But the process proved prohibitively expensive for both filmmakers and exhibitors, soon giving way to less extreme but more practical formats.