Three old ladies sit on a bench inside Père Lachaise. They have just visited the tombs of their late husbands and joke about one being near Jim Morrison’s heavily trafficked grave. “He doesn’t bother us,” one widow says. Relaxing in the shade with the ease of a familiar ritual, their arms are folded across pocketbooks resting in their laps. Prompted by a comment about her accent, the woman closest to the camera begins to talk. She came to France fifty years ago to flee Franco’s Spain—“We had different ideas,” she says by way of explanation. She recalls how she and her husband could hear the clacking of chains as captives moved into the prison courtyard, just over the terrace wall, followed by the rifle shots of the firing squads and final pop of a pistol—“Most had to be finished off.”

That you’ll find death here is no surprise but the lives revealed in Heddy Honigmann’s Forever, set almost entirely in the Paris cemetery where some of the world’s most celebrated deceased are buried alongside the unknown or forgotten, have the potential to drop your jaw. Such stories lie behind each pair of eyes in the work of the Amsterdam-based filmmaker who has been peeling back the veil of presumption at least since 1993’s Metal and Melancholy.

The child of Holocaust survivors who fled to Peru, Honigmann moved back to Europe to study and settled in the Netherlands. In the early 1990s, she returned to her natal home in the wake of a devastating financial crisis that had resulted in, among other economic catastrophes, a thirteen-percent rise in the number of Peruvians living in poverty. For Metal and Melancholy, Honigmann takes her camera and gently prodding curiosity into the passenger seats of Lima’s plentiful taxi cabs to interview the new underclass. From a publicist to a number-cruncher to a cop, legions of white, pink and blue collar workers take to the streets in their off-hours using their cars, whatever shape they are in, to try to make ends meet one fare at time. There are so many cabs in fact that an ancillary business springs up, “taxi” stickers hawked car to car in the city’s dense traffic.

The cabbies’ stories are alarming but Honigmann knows that sad-sack tales are a dime a dozen. Instead, she peels back the obvious to reveal the Peruvians’ talents and ingenuity for getting by. The retired air force officer, who teaches military science at the academy, also occasionally roasts nuts at home to sell on the street. A Ministry of Justice comptroller, who lives in a stripped down apartment with his wife and four young children, demonstrates the use of the car battery set up on the kitchen window sill for when the power goes out.

An older driver sings plaintively as he wheels around Lima. Back inside his cab later in the film, he opens his glove compartment, offering up a box of ballpoint pens for sale. “I have piles of pens,” says Honigmann. He reaches in even farther for a repurposed Chiclets box now storing a stack of small homemade cakes. “We can settle it with the bill,” he tells her. A few more seconds with him and we learn he’s an actor who’s appeared in small roles in several national motion pictures, including one based on a novel by Mario Vargas Llosa, and in the soap opera Gamboa. While we ride along, he seamlessly transforms into a general breaking composure over the recent loss of his son. “You really cried,” says Honigmann after the performance. “Maybe,” he says, with a chuckle. “Maybe.”

Honigmann’s characters know they must play their roles, tell the story they told before—the reason they were chosen for the film in the first place—like it’s the first time. In the very next scene, a few children approach her one at a time at a sidewalk café, playing up their innocence or displaying insouciance, whatever it is they usually must do to cajole folks into buying a crocodile tchotchke, a roll of candy, a pack of cigarettes. One savvy kid enters into an improvisation with the director, who remains unseen behind the camera. He stands in front of her, expressionless, waiting his cue. (mytravelintuscany) “Go away,” says Honigmann. “I don’t want any candy.” “But I just need to sell one. Or maybe two.” He smiles. “What’s your name?” “Jorge.” He waits a beat. “I’m a tradesman.” He’s maybe ten or twelve years old; his entertaining gambit—a lesson in how not to end up on the cutting room floor—is just part of knowing about survival. Honigmann includes it so we know, too.

One of her strengths as a director is keeping these stories, most of which she’s heard before, fresh for the camera. She’s so good at preserving spontaneity that viewers might think she simply walks up to a stranger on the street, asks an impertinent question, and gets lucky. (I’ve heard her complain in an interview—just a bit—about this kind of illiteracy in audiences.) In an outtake for a 2008 documentary about making documentaries, Capturing Reality, she offers an example of getting what she wants on camera without making it seem rushed or canned.

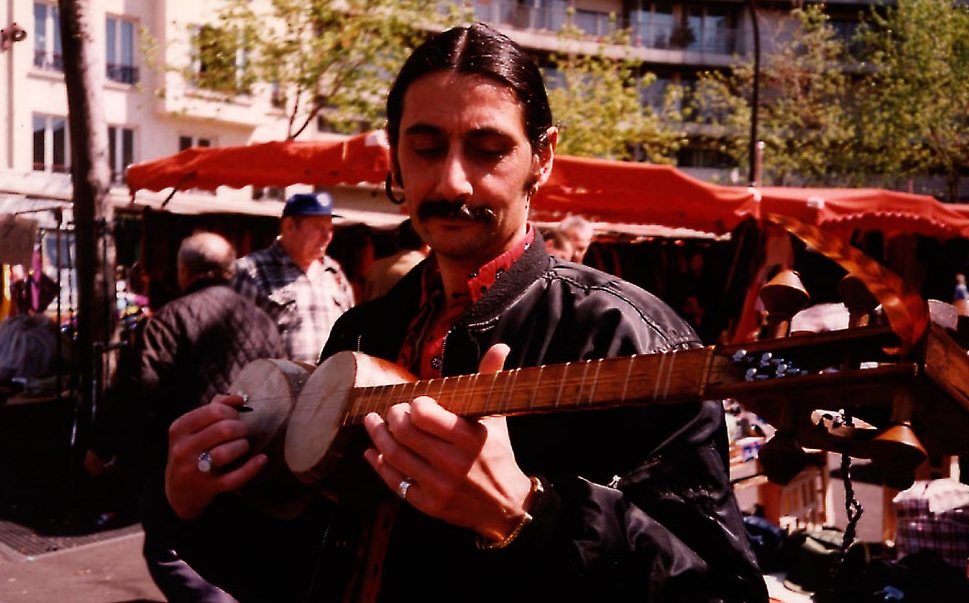

During pre-production for Underground Orchestra she had been at a café talking with Georges, a Romanian classical guitarist, one of her main characters and one of the many émigrés in the film come to Paris out of necessity. Unexpectedly his son Eliad stopped by and made an offhand comment about his father’s music being old-fashioned. A year and a half later when it came time to shoot, Honigmann wanted to recapture that moment at the café now that film was rolling.

She decided to have them perform together. The father, at his guitar, and son, arriving late with his violin, have a few tense moments but are restrained because of the guests and the camera. They play a beautiful duet, a Chopin, I think, then the director laments not begin able to play like that with her own son. A conversation ensues. Honigmann asks what the son would have played had he picked the piece. “Beethoven,” he answers. “Why?” Then Eliad rolls out a brilliant string of analogies between classical composers and rock musicians: Beethoven is Jimi Hendrix; Shubert is Jim Morrison; Wagner is Motörhead; Bach is AC/DC.

“Sounds like a medicine,” the father says, half smiling. It’s funny but it’s also a melancholy moment in the film—Georges sees his son has completely moved away from his own musical references: he is not only more rock and roll than classical, more French than Romanian, but he is a man with his own opinions. The moment is spontaneous yet completely engineered, and, yes, a little lucky.

Jorge Kanashiro in Oblivion knows what performance is all about. For the 2008 documentary Honigmann is back in Lima. It’s fifteen years later, and Peru has reelected the same president who had provoked the crisis of the early 1990s, and the lower classes are still trying to survive. Mixing Pisco sours by night—sometimes for these very presidents—the bartender “daylights” instructing service industry aspirants at a technical school. “Smiling must be taken seriously,” he says, “We are actors in the service sector. I’d even say the very best actors. Perfect acting; that’s what service is all about.”

In Oblivion it becomes apparent that waiting tables is the taxi-driving option of the new century. Among Honigmann’s characters are a street juggler taking Kanashiro’s class, a waiter who’s worked more than fifty years at the same café, and a middle-aged waitress at a more downscale restaurant. We accompany the waitress as she closes down the place and, in the twilight, begins her long slog home: sitting in a van in traffic, then in a covered scooter, then on foot when the motorbike gets a flat. Inside her dimly lit home she tells the story of how life got a lot harder after her divorce. She and her son had to move in with her mother. She gets choked up. “The important thing is that we are together,” she says, turning to her mother. “Until winter comes and we freeze to death,” the mother says. A bit of luck or a bit of engineering? It doesn’t much matter. Sentimentality has no place here.

An empathetic interviewer, Honigmann knows when to shut up and let people talk and when to allow let moments to unfold visually. She punctuates Oblivion with television footage of a string of presidential inaugurals, each politician taking the pledge to faithfully uphold the office which the nation has entrusted to him. From Alan Garcia down to Alberto Fujimori, they repeat the words, make the gestures, without commentary from Honigmann, who uses this strategy to different effect with Oblivion’s ordinary Peruvians.

Jorge delivers drinks to a table whose ambient light comes largely from a backlit aquarium holding a pair of live dolphins. Two young girls perform cartwheels for change at traffic stops at night. The juggler/aspiring waiter, his colored clubs peeking out of his knapsack, a bag of groceries in each hand, climbs a steep hill home. Up one long set of stairs, he passes by someone’s laundry hanging out to dry. He greets the stray dogs, a few neighbors, then, another set of stairs. Honigmann wordlessly follows him, sometimes close behind, other times sidelong or at a distance. We watch him for a full minute and a half. When she finally cuts, he’s about to reach another set of stairs.