In “Dancers, Buildings, and People in the Street,” a talk Edwin Denby prepared (but never delivered) for dance students at Juilliard in 1954, the poet and critic offers that a formal dance performance is most basically arranged “so that it is convenient to look at, easy to pay continuous attention to, and attractive, but also that the excitement in it seems to have points of contact with the excitement of one’s own personal life.” Denby follows this point by adding that the appreciative gaze that goes along with watching such a performance needn’t be limited to the stage: “For myself I think the walk of New Yorkers is amazingly beautiful, so large and clear.” The film camera is similarly all-inclusive of what constitutes a dance performance, as demonstrated by the ranging scenes listed below. Though widely divergent in their formal approaches, these clips share a common festivity in the way they allow us to become absorbed in the emotional energy and sheer physicality of bodies moving in rhythm.

Film scholar Tom Gunning describes the earliest days of filmmaking as producing a “cinema of attractions,” and it’s easy to see why watching these dancing kinetoscope subjects shot in Thomas Edison’s Black Maria studio by William K.L. Dickson and others. The then fresh wonder of moving pictures is especially evident in Annabelle Butterfly Dance, in which Annabelle Whitford’s elaborate costuming unfolds an exuberant degree of graphic detail. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was a particularly popular source for these early films, and Native American subjects like Buffalo Dance and Sioux Ghost Dance link the curiosities of vaudeville and pseudo-ethnography. Though dubious as a cultural document, the short films nonetheless forge a kind of axiomatic relationship between moving images and lithe bodies in motion (boxers, trapeze artists, and rodeo cowboys similarly register as dancers in these films). Perhaps the oddest dance among the Dickson’s films is that of two Black Maria male employees awkwardly making the rounds in the Dickson Experimental Sound Film. The technological wonder of this film cannot quite overcome the strangeness of its graphic composition.

The Very Eye of Night (1958, Maya Deren)

Maya Deren did as much as anyone to conceptualize a distinctly cinematic approach to dance; in her hands, cinematography and editing became fresh tools for choreography. Several years after her fully achieved camera duet with Chao Li-Chi, Meditation on Violence, Deren collaborated with members of the Metropolitan Opera Ballet School on The Very Eye of Night, an ethereal foray into the mythical basis of dance. Freed from the bounds of perspective and gravity the dancers’ polarized forms play upon a starry backdrop as if they were constellations sprung to life. Deren’s camera moves with the same unrestrained fluidity of her earlier films, only here the beauty of the dancers’ forms is fully transposed into a pure realm of imagination and beauty. Deren will always be thought of as one of the progenitors of American avant-garde cinema, but The Very Eye of Night vision of body and cosmos in harmony is fundamentally classical.

Cerveza Bud (1981, Rudy Burckhardt)

Street photographer and filmmaker Rudy Burckhardt was a longtime confidante of Edwin Denby’s, and the two doubtlessly shared a Whitman-esque love for the manifold poetry found on the streets of New York. Burckhardt’s city symphonies are distinctly human scaled, driven by an innate curiosity for pattern and spontaneous expression. The delightfully titled Cerveza Bud exudes the same omnipresent sexuality as its subject: New York on a muggy summer day. Ever attentive to fantastic variations of dress and self-presentation, Burckhardt’s camera observes lovers sprawled out in the park and busybodies promenading down the avenue. Though he actually filmed professional dancers on the same city streets in his Night Fantasies, Cerveza Bud’s amorous portraits of a Puerto Rican parade, drum circles, a topless dancer, gliding gods and goddesses on roller-skates, and a few fabulous male dancing partners turning endless circles to disco radio gets closer to his signature joie de vivre.

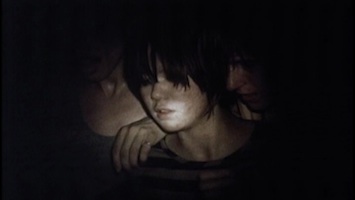

Black and White Trypps III (2007, Ben Russell)

An ideal companion to Deren’s The Very Eye of Night, Ben Russell’s third Trypps film splits the difference between raw document and spiritual invocation. The continuous but nonetheless fragmented image highlights the collective ecstasy of the audience at a Lightning Bolt concert (the fiery Providence duo is as much known for eschewing the concert stage as producing caterwauling sheets of sound). The image is roughly from the band’s perspective, with a small spotlight illuminating a small section of the frame. Into this halo passes the faces of those young concertgoers submitting themselves to the intensely physical music as a kind of rite. Russell’s framing emphasizes the private moments of rapture even as the bodies press up against one another undulating as a single mass. Likened by several critics to devotional paintings, Russell’s film has a far greater impact in the cinema space where the black within and around the frame engulfs the spectator along with figures onscreen. Make sure to at least turn it up loud when watching at home.

35 Shots of Rum (2009, Claire Denis)

Claire Denis’s story of a father and daughter leaves a good deal of character development to body language, never more so than in the impossibly romantic dance scene at a restaurant on a rainy night. Lionel (Alex Descas) and his daughter Joséphine (Mati Diop) are going to a concert with Gabrielle (Nicole Dogue), Lionel’s onetime lover who still has feelings for him, and Noé (Grégoire Colin), Joséphine’s on and off lover, but Gabrielle’s car breaks down on the way and the group seeks shelter in an African restaurant. It’s a magical place: food comes without being ordered, the music is terrific, and unresolved desires suddenly surface. Lionel allows Noé to cut in with Joséphine as a mellow salsa gives way to the Commodores’ sinuous “Nightshift.” Lionel seems to be playacting giving his daughter away, but the tone shifts when Noé lets down a slightly embarrassed Joséphine’s hair with erotic élan. A decisive cut to Lionel watching strikes a complex chord of love and regret, one layered with the subsequent cut to Gabrielle watching Lionel dance with the restaurant’s owner. Denis realizes a distinctly musical approach to characterization by having all these complex emotional strands emerge in the unspoken flow of dance.

Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench (2010, Damien Chezelle)

The black-and-white 16mm look and low-key romantic roundelay of Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench evokes mumblecore, but while Chezelle’s characters may be similarly circumspect in speech they are also given to wonderful flights of expression in song and dance. Less than twenty minutes into the film the titular trumpet player (Jason Palmer) has already left Madeline (Desiree Garcia) for Elena (Sandha Khin) after a steamy subway encounter. That meeting is shot very much as a dance, but it’s only with this noisy house party scene that the movie definitively takes imaginative license as a musical. A bearded gent bursts into song; a live piano and drum accompaniment isn’t far behind. The singer can tap dance too (so can the initially reluctant girl he pulls off the piano). It’s delightful having this kind of implausible spontaneous musical number materialize within a normally incommensurate long take verité aesthetic. The cramped apartment space means that the handheld camera must quickly pan between the tap dancer and Guy trading solos from a separate room. When the camera draws into the main room for a close-up of a drum fill, it spins around just in time for a close-up looking into Guy’s horn as he blows a sweet melody. What finally links musical scenes like this one to Guy and Madeline’s romantic entanglements is a little thing called chemistry.