Cinephiles asked to peg a favorite “golden era” in the hundred-plus years of the medium might have a hard time choosing between, say, Silent German Expressionism, Hollywood’s saucy “pre-Code” gems or its post-WWII noir vogue, the French Nouvelle Vague, Hong Kong’s visceral action films, or the more recent Romanian maxi-minimalists. For me, a favorite is Czechoslovakia’s New Wave.It occupied a roughly equivalent timespan as America’s ’60s-’70s counterculture filmmaking (another personal pick), although the Czech New Wave was curtailed much earlier by a Soviet-invasion clampdown on the giddy political and cultural liberalizations of early 1968’s Prague Spring. Many of the country’s brilliant emerging filmmakers went into exile (most famously Miloš Forman, who’d re-invent himself as the successfully transplanted director of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus), while others stayed and suffered censorious, immediate career cutoff. Enough remained active, however—despite whatever creative compromises were being forced on them by sterner new governmental overseers—to extend this cinematic Renaissance by a few years. Some, their work so deeply idiosyncratic it flummoxed censors seeking ideological fault, continued more or less unabated for decades, ironically suffering more from the 1989 Velvet Revolution, whose democratization relaxed free expression but also introduced a new urgency for non-government funding and box-office viability.Czech cinema of the ’60s was gorgeous, sardonic, abstract, tender—a mess of contradictions nonetheless somehow nationally distinct in its mastery of emotion and image. It encompassed the warm social satire of Forman (The Fireman’s Ball), fellow Hollywood-adopted evacuee Ivan Passer (Intimate Lightning), and marvelous Jiri Menzel (Closely Watched Trains). There was also grotesque animation master Jan Svankmajer; Frantisek Vlacil of the extraordinary medieval epics Marketa Lazarova and Valley of the Bees; the antic, visually extravagant Juraj Jakubisko (Birds, Orphans and Fools); plus assorted other fantasists and visionaries that variably flourished after the anti-democratization whip came down.

Czech cinema of the ’60s was gorgeous, sardonic, abstract, tender—a mess of contradictions nonetheless somehow nationally distinct in its mastery of emotion and image.

Two among the latter are spotlit in a short, sharp flashback to this golden era offered by Berkeley’s Pacific Film Archive June 9 through 29 under the no-nonsense title “Three Czech New Wave Classics.” Their selection determined by the vagaries of currently available 35mm prints from the Czech National Archives, the PFA series showcases—perhaps only by lucky accident—the more freewheeling, experimental, visually extravagant side of an already heady moment in film history. Trust me: You could do a lot worse.Claiming two out of the three titles is Věra Chytilová, one of the earliest and longest-lasting participants in said New Wave—though with a filmic sensibility as prickly, wacky, and stylistically distinctive as anyone from Fellini to Tim Burton, she ought to be far better known internationally by now. Her 1966 Daisies is like nothing else: A surreal pop-art comedy whose proto-riot-grrl protagonists (Ivana Karbanova, Jitka Cerhova) are two young women whose shameless hedonism—almost entirely gastronomic—gets exercised via acts of random theft, predation on gullible “sugar daddies,” and musical comedy.

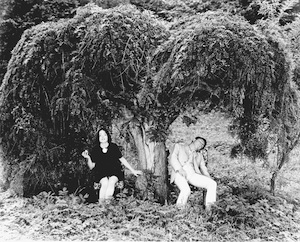

Those acts are illustrated in terms variously slapstick, avant-garde, B&W, time-lapsed, and prism-colored-hallucinogenic. At one point the heroines literally scissor themselves into an onscreen collage of body parts. While they might be exaggeratedly soulless consumers on the surface, the prankster spirit with which they’re presented has made them anarchistic icons to every feminist cineaste I’ve ever known who’s been exposed to their delightfully, destructively self-interested company. They are brats whose obstinate insistence on Me First is subversive—simply because it takes for granted a self-centered universe normally granted without comment to boys only.Though offered to authorities as a parody of Western consumerism and advertising imagery, Daisies looked a little too subversive to the still-conservative Czech cultural watchdogs of 1966. It got banned at home, despite widespread acclaim on the festival circuit. Chytilová was allowed to make a subsequent feature several years later. But that film would stir even sharper rebuke from the censors, ending her career entire until the late ’70s.The movie in question is the PFA’s second “Czech New Wave Classic.” Fruit of Paradise, as ripe an objet d’art as ever witnessed the intersection of Jonas Mekas and narrative cinema. Its Eve (Jitka Novakova), Adam (Karel Novak) and red-velvet-suited Satan (Jan Schmid) traverse a psychedelic child’s garden of primitive-to-modern goods ‘n’ evils florid, funny, and flummoxing as all get-out. Again, it’s like nothing else—executed with such blithe originality and transgressive feminine cinematic imagination and style. (You might raise the specter of Lina Wertmuller…but then again, please don’t.) While the film eventually runs out of ideas, its exhausting energy never flags.Chytilová persevered. Her later movies—now 80-plus, she remained active at least up to six years ago—continued to be crazily inventive, at least insofar as rare international audiences could decide. (Translated titles alone suggest their stubborn eccentricity: A Hoof Here a Hoof There, My Pragues Understand Me, The Inheritance or Fuckoffguysgoodday.) She even scored the odd quasi-genre home-turf hit, like Wolf’s Cabin (1986), a goofy pseudo-slasher. Here’s hoping her entire oeuvre will one day be more widely available for appreciation.

Věra Chytilová, one of the earliest and longest-lasting participants in the Czech New Wave, with a filmic sensibility as prickly, wacky, and stylistically distinctive as anyone from Fellini to Tim Burton, ought to be far better known internationally by now. Her 1966 ‘Daisies’ is like nothing else: A surreal pop-art comedy whose proto-riot-grrl protagonists whose shameless hedonism—almost entirely gastronomic—gets exercised via acts of random theft, predation on gullible ‘sugar daddies,’ and musical comedy.

In the meantime, there’s a third PFA-showcased title you can also find—if you look hard—available on DVD. Jaromil Jires’ 1970 Valerie and Her Week of Wonders epitomizes Czech New Wave stylistic abandon even as it defines an apolitical fantasy strain that was one of few avenues allowable to filmmakers after the post-Prague Spring-crackdown. (The only real-world institution critiqued here is a corrupt church, a subject that always found favor with the Communist regime’s anti-religion stance.)A 13-year-old girl named Valerie (Jaroslava Schallerova, actually if improbably that age during production) is a crimson-haired kewpie of precocious looks and manner, living in a village out of time. Her mother and father long missing, she’s being raised by a white-haired Granny in prim Victorian black (Helena Anyzova, a 30-something beauty in deliberately unconvincing “old” makeup), who pulls her pubescent charge in the direction of well-intentioned repression. Pulling in the other direction is The Weasel (Jiri Prymek), a chalk-faced predator who resembles Death in The Seventh Seal but appears in many guises—none of them good, including as vampire and lascivious priest. Then there’s bespectacled hero Eagle (Petr Kopriva), with whom she seems to share some vague, as-yet-chaste romantic urges. Despite the fact that he may be her brother.Valerie’s cusp-of-womanhood ripeness (she’s just begun to menstruate) brings the wolves out of the primeval woods in bulk. Even Granny starts giving off kinky vibes when she makes a deal with the devil to regain her youth. Light bondage, some nonsense about magic earrings, roving self-flagellant packs, and much dreamlike Gothic imagery ensue. Freud would have loved Week of Wonders, and many others have—including novelist Angela Carter and several indie rock bands who’ve recorded homages. It’s easy to see the cult appeal of a fable suspended between traditional fairy tale, horror movie, and arty erotica, whose sumptuous soft-focus visual presentation recalls other screen favorites of decadent fantasy exoticism, from Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast to Tarsem’s The Fall.But with its quintessential faux Sapphic male-gaze interludes and obsessive sexualizing of a “pure” underage girl within an anti-sex narrative context, Valerie can also be viewed as a whopping dose of ornate kitsch. It certainly proved the late director Jires, who enjoyed a long career from the late 1950s to century’s end, was versatile, not to mention adaptable: Its gaga color fantasia directly followed 1969’s B&W The Joke, a Milan Kundera adaptation so sharply political it was not only banned but expurgated from his filmography for years. The two would make a fascinating double bill.