There are known knowns; there are things we know that we know.

There are known unknowns; that is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know.

But there are also unknown unknowns – there are things we do not know we don’t know.—Donald Rumsfeld, February 12, 2002

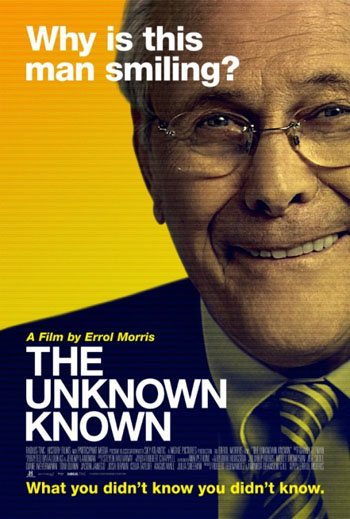

We begin with Rachel Donadio, reporting from Venice for the New York Times: “‘I’ve made a whole number of movies over the years about characters that seem to be completely unaware of themselves. I suppose in English the word that we often use is “clueless,”‘ Errol Morris said at a news conference here on Wednesday to promote The Unknown Known, his new film-length interview with Donald Rumsfeld, the former secretary of defense. ‘That’s the central feeling I’m left with at the end of making this movie. What is he thinking?’ Mr. Morris continued about Mr. Rumsfeld. ‘Is this a performance? Is he acting? Does he believe in what he is saying? I would say it’s the central mystery of this movie: Who is Donald Rumsfeld?'”

If Morris is tacitly acknowledging that he’s been expected to, shall we say, nail Rumsfeld and has failed, most critics agree. So the next question would be, what else is there to The Unknown Known?

“A typically handsome, charcoal-hued effort, it has plainly been conceived as a structural and thematic bookend to The Fog of War, Morris’s Oscar-winning interrogation of another former Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara, with a lot on his conscience,” writes Guy Lodge at In Contention. “In his smooth but insistent way, Morris cracked McNamara: there was no cathartic mea culpa on his Vietnam decision-making, of course, but his open engagement and reasonably candid self-evaluation was victory enough. If Morris was hoping to tease out this degree of consideration in Rumsfeld, he’s out of luck.”

“The film winds up as a tense, frustrating stalemate,” adds the Guardian‘s Xan Brooks. “Did the Bush administration promote the misconception that Saddam Hussein was somehow responsible for the September 11 attacks? No, says Rumsfeld, of course they didn’t, although Morris has a tape of Rumsfeld himself doing precisely that. Did the interrogation tactics used at Guantanamo lead to the prisoner abuse scandal at Abu Ghraib? Nonsense, says Rumsfeld, despite a report that found otherwise…. Rumsfeld is a man whose neo-con vision was shaped by the attack on Pearl Harbor and the fall of Saigon—both of which he puts down to a ‘failure of imagination’ on the part of the US government. As defense secretary, he was determined not to make the same mistake.”

“Morris has built his picture around a trove of Rumsfeld’s memos, which were written throughout an almost 50-year career that has taken in stints in Congress, the White House and the Pentagon,” writes the Telegraph‘s Robbie Collin. “Rumsfeld gamely reads the memos aloud and then Morris quizzes him about their content… Well, Morris gives it the old college try, but Rumsfeld is too smooth an operator to let anything slip: at 81 he twinkles like a clean-shaven Father Christmas, and when confronted with a question he doesn’t much like, he simply clicks the detour button on his verbal Sat Nav and talks his way around it.”

“He doesn’t come across as a particularly affable and humane guy, boasting of how he chose to marry his teen sweetheart less out of love and more out of logistical necessity,” notes David Jenkins at Little White Lies. “Hell, when you’re dealing with a man who even Nixon despised, then you know you’re in big trouble. Yet, the film’s failure to offer any big revelations is just as much Morris’s fault as Rumsfeld’s, as he too often feeds questions to his subject in a jokey, barroom manner which highlights a potential intellectual chasm between interviewer and subject.”

“Instantly recognizable as a Morris documentary by virtue of the fancy visuals and the pulsating musical accompaniment provided by Danny Elfman,” writes the Hollywood Reporter‘s Todd McCarthy, “in The Unknown Known all this is merely window dressing to distract the viewer from the fact that we will probably never know what goes on inside Rumsfeld’s head.”

Screen‘s Lee Marshall finds the film “fascinating” nonetheless: “What emerges from Morris’s careful chipping away at his man is not cathartic, as with McNamara, but chilling—the dizzying prospect that beneath Rumsfeld’s desire not to give anything away, there may actually be nothing to give away. It’s as if the exercise of power has emptied him out on the inside, and all that is left is the professional mask, the hollow phrases, and that famous, mocking rictus smile. If documentaries slotted into feature film genres, this one would be close to horror.”

“Taken collectively, McNamara and Rumsfeld are signposts on the long and winding road of modern American geopolitics, as it veers from men of real vision (for good or ill), forged by the Great Depression and the New Deal, to professional bureaucrats hopelessly in love with the sound of their own voices,” writes Variety‘s Scott Foundas. “Not for nothing is Morris’s most indelible image here that of a vast canvas of gently lapping waves suddenly transformed into a literal ocean of words.”

Giving it a B at Indiewire, Eric Kohn finds The Unknown Known to be “a peculiar movie seemingly at war with itself.” Interviews with Morris: John Horn (Los Angeles Times) and Marlow Stern (Daily Beast).

Competing in Venice, The Unknown Known has screened at Telluride and is part of the TIFF Docs program in Toronto.

Update: At the Playlist, Oliver Lyttelton gives the film a C.

Updates, 9/7: “If Rumsfeld had sat down with Michael Moore, or David Corn or Ezra Klein, or even Jon Stewart, his almost messianic belief in the rightness of his doctrine and policies might have taken some serious challenges, his steely poise a few dents,” suggests Mary Corliss in Time. “The resulting conversation would have contained a few known unknowns. But Morris’s movie is a cat-and-mouse game, and Rumsfeld is the cat, virtually licking his chops as he toys with, and then devours, another rival.”

Morris “seems unable to find a proper visual complement for his subject’s paradoxes and insurmountably insane intentions,” writes Samuel Prime at the House Next Door. “What results is overlaid definitions of words and interstitial scenes of what feels like random stock footage, from helicopter shots over large bodies of water to first-person footage of planes flying at breakneck speed through the clouds…. What Morris failed to realize is that nothing this film could offer is more powerful or haunting than the lingering smirk that follows one of Rumsfeld’s prideful diatribes.”

Update, 9/9: At the Dissolve, Scott Tobias argues that “as the title suggests, Morris turns The Unknown Known into a documentary about obfuscation, highlighting the ways Rumsfeld used specific words and phrases to cover up his inept decisions and the simple, confused, inflexible thinking that led to them. It’s much better-sounding for Rumsfeld to say the chaos that followed Iraq’s ‘liberation’ couldn’t be anticipated than for him to admit specific errors in planning. And while Rumsfeld’s elusiveness makes a thin gruel out of the biographical elements of the film—including his almost Zelig-like ubiquity during Republican administrations from Nixon to Reagan—Morris turns the Bush years into a character study that’s revealing in how little is revealed.”

Updates, 9/11: “The Unknown Known skews closer to Tabloid than The Fog of War, a distinction that is less flattering of Morris than it is condemning of Rumsfeld,” writes Jay Kuehner in Cinema Scope. Still, as a history lesson in digest form, it’s eminently valuable for cracking Rumsfeld’s cheshire grin without employing unsound interrogation methods.”

“McNamara’s policy,” notes Ben Kenigsberg at the AV Club, “was, ‘Don’t answer the question you were asked. Answer the question you wish you were asked.’ Rumsfeld takes this to another level, giving contradictory answers at different points throughout the interview.”

“The film’s most interesting content is not to be found in the airless, non-revelatory discussions about post-9/11, Dubya-era America,” writes Ashley Clarke for Sight & Sound, “but rather on his meteoric ascent through the Washington power structure, beginning in the 1960s. Constructed from a patchwork of Rumsfeld’s memos, often read aloud by the man himself, and reams of archive material and photography, these passages paint a picture of a canny player with an inscrutable plan.”

“Did anyone trust Rumsfeld?” asks David D’Arcy. “Not George Bush Senior, maybe not Cheney, not his core generals. But surprisingly, Rumsfeld today has a fondness of Tariq Aziz, the former Iraqi Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, now sentenced to death for his role in the execution of merchants accused of sanctions profiteering in 1992—from which Saddam benefited. What does Aziz know? He is still alive, for all we know.”

Rumsfeld, notes Anthony Kaufman at Sundance Now, “uses words, and his own preferred lexicon, as a protective shield, which resonates with Morris’s lifelong interest in the ways our perceptions shape and distort reality.”

“As a documentary journalist, what do you with a man like this?” asks EW‘s Owen Gleiberman, arguing that “to make the playfully convoluted, semi-nonsensical aggression of his language the whole point is, in a way, to fall into the trap of mistaking the spin for the story. I guess you go into a movie with the big-fish interview subject you have, but the bottom line, for me, is that Errol Morris should have waited to make a film about Dick Cheney, who’d probably reveal more to the Interrotron when he was revealing nothing than Donald Rumsfeld does when he won’t shut up.

Anne Thompson‘s got a lengthy exchange from the post-screening Q&A in Toronto.

Updates, 9/14: “The Fog of War is the superior film, but The Unknown Known is more unsettling,” writes Jake Cole at Film.com. “Rumsfeld speaks of his memos as historical documents, but the sad truth hanging in the air around Morris’ Interrotron setup is that they have yet to become artifacts of the past.”

At Film Comment, Nicolas Rapold notes that “one thing is certain: the film reinforces the eternal point that one of the biggest weapons in war is language.”

“Packed with blatant illustrations (swamps! snow globes!) and insistent Danny Elfman chorales,” adds Fernando F. Croce in the Notebook, “it’s nevertheless the kind of meeting where an unilluminating outcome speaks volumes about the subject.”

Jeff Labrecque talks with Morris for EW.

Update, 9/21: “No one’s ever going to call him dull,” writes Tom Carson of Rumsfeld in the American Prospect. “Not only did he have the best brain of anyone in Bush 43’s inner circle—in the classic Ivy League mold, to be sure, meaning it was all cunning and no wisdom—but he was its only genuine wit. Yet neither of those is a moral quality, and Rumsfeld’s complacency is even more abrasive now that he’s had six years to ponder—or not—his disgraceful place in history…. Then as now, the vital ingredient in Rumsfeld’s self-regard is his notion that he doesn’t suffer fools gladly. The problem there is his capacious definition of fools, which more or less comprises the planet at large aside from Dick Cheney—and he’s not so sure about Dick, as the saying goes.”

Update, 10/11: “One might guess that the best way into Donald Rumsfeld is through his association with Dick Cheney, and the way those two men ran the world for so long,” writes David Thomson in the New Republic. “That would require years of research and many interviews to restore the mosaic of a crucial friendship in political life. There is such a film, The World According to Dick Cheney, directed by R. J. Cutler… It is sometimes more informative and provocative than The Unknown Known. Cheney never hides his serpentine nature, whereas Rumsfeld can play all the animals in the menagerie, especially the Cheshire Cat, who will leave his cocksure grin hanging in the air, smug that ‘documentary’ never laid a glove on him. Rummy knows how the media work, and he has seen that if you stare long enough into Morris’s Interrotron lens its intimidating force wilts. ‘Chalk that one up to me, Errol,’ he crows at one point in the film.”

Update, 12/1: For the New York Review of Books, Mark Danner takes on Rumsfeld’s memoir and Bradley Graham’s book By His Own Rules: The Ambitions, Successes, and Ultimate Failures of Donald Rumsfeld. As for Morris’s film, he finds it “brilliant and maddening.”

2013 Indexes: Venice, Telluride, and Toronto. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.