Let’s begin with Michael Pattison‘s fresh report here in Keyframe on last month’s Locarno Film Festival, wherein he notes that Pedro Costa‘s “long-awaited Horse Money presents an associative hotchpotch of memories pertaining to the experiences of displaced Cape Verdians now living in Portugal. Following on from Colossal Youth (2006), it again features his regular performer Ventura—this time a trembling bag of nerves moving from one eerily quiet room to the next of something resembling a mental hospital. Exquisite compositions and delicately delivered dialogue build to a cumulative tone-poem on the traumas felt today by an exiled people still coming to terms with the prolonged fallout of imperialism.”

Paul Dallas in a dispatch to Filmmaker: “Costa sets the agenda early on with a slideshow of Jacob Riis photos, and the film culminates in a 20-plus minute sequence locked inside a hotel elevator, representing the psychic space of its lead character Ventura. Costa walked away with Best Director and also walked away from Locarno before the awards were handed out.”

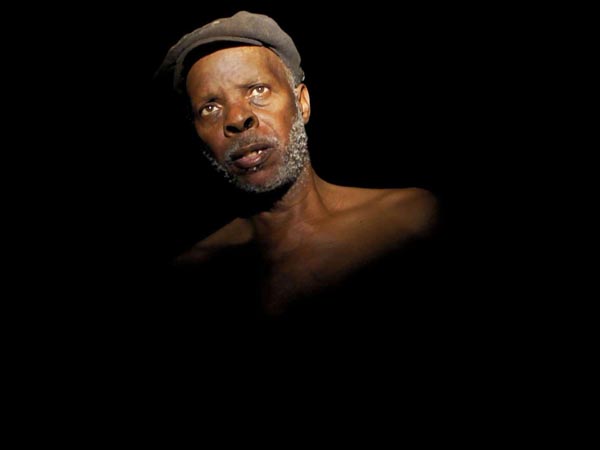

“Ventura’s journey into what Costa has called ‘a Baudelairean night’ transpires outside the realm of rationality, framed in expressionist angles, as darkly lit as Caravaggio, and, in no uncertain terms, resists a neat summary,” writes Mark Peranson, Cinema Scope editor and Head of Programming at Locarno, at the top of a must-read interview with Costa. “About as torturous to revisit in writing as it is to watch, the most true-to-form analysis of Horse Money should proceed in this painstaking way, shot after shot, because to examine the film as a whole, or as a connection of scenes that flow one into the other, is an impossibility. (Every review of this film is guaranteed to get at least one detail wrong; after seeing it three times the film remains intangible to me.) And this is the way Costa wants it, with Ventura’s mental landscape receiving a tangible form of resistance in the film’s aesthetics: like Jean-Marie Straub, Costa adheres to the philosophical impossibility of matching one shot to the next.”

Mark Peranson conducted the Q&A that followed the screening in Locarno

“Even trying to take in and digest this onslaught of ideas and the infinite web of relationships they form is futile,” writes James Lattimer at the House Next Door. “Yet what makes Horse Money such a striking achievement is how unique the experience of getting lost in its maze of thought and image really is, at once confounding, disquieting, stimulating, and hugely emotional, not least in one extended monologue that ends by describing the violent death of a horse called Money. Despite the film’s utter singularity, I was oddly reminded of Inland Empire at times, another late-career work that goes about creating a summation of sorts by collapsing all boundaries.”

“Costa has been filming the people of Fontainhas for two decades now (since his third feature, Ossos, in 1997), burrowing ever deeper into their lives, adapting his filmmaking methods to their environs, and together with his subjects forging a new kind of poetic realism,” writes Variety‘s Scott Foundas. “And if Horse Money is unmistakably a continuation of Costa’s general line of inquiry, it also feels like a further refinement of his technique, from its comparatively taut running time (under two hours) to the shadowy expressiveness of the HD imagery. This is a movie of long, crypt-like corridors stretching toward infinity, and of screen-filling close-ups (shot by Costa and co-cinematographer Leonardo Simoes in the square Academy aspect ratio) that seem chiseled from the darkness, like living sculpture. The camera itself rarely moves, but when it does, it does so with urgency and purpose.”

“The question of whether or not Costa aestheticizes poverty is somewhat irrelevant,” argues Ignatiy Vishnevetsky at the AV Club, “because, first of all, he obviously does, and, second, because in doing so he transforms the experiences of his characters—all non-actors who play fictionalized versions of themselves—into tragic, plainspoken, often funny poetry that records the specifics of the impoverished immigrant experience while making it part of a larger cycle of social exploitation…. Costa’s work is beautiful because of how it frames and paints emotional and mental states that are the result of difficult lives, not because it pretends that social tragedy is inherently beautiful.”

“The asylum setting is telling, for this unrelentingly expressionistic horror story can stand with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” writes Fernando F. Croce in the Notebook. “Encircled by the deepest chiaroscuro I’ve ever seen (more silent-film linkage: like Griffith, Costa uses darkness to reshape the frame), characters recite birth and marriage and death certificates in desperate murmurs, attempting to reinforce their existence as something other than phantoms…. By the time the film reaches its devastating final image, I was trembling as much as the protagonist.”

Also in the Notebook, as noted earlier, Adam Cook: “Costa uses light and shadow to work with texture and geometry, creating a such a level of visual richness that the shots are barely long enough to fully absorb them. In fact, these are not just the most beautiful images here in Locarno, but some of the most stunning of all I’ve seen in cinema—each shot its own complete world of depth and feeling. It’s a cliché perhaps to refer to a film as ‘hypnotizing,’ but never has it been more true. The film presents a world that itself seems hypnotized, examining its own subconscious.”

“Horse Money is likely the Costa film that best exemplifies the influence of classical Hollywood genre cinema on his work, with both the ghostly hospital where Ventura resides and the looming hell-tunnel he frequently travels feeling like they came straight out of a Jacques Tourneur or Fritz Lang film,” writes Ethan Vestby at the Film Stage. “This isn’t only apparent in Costa’s immaculate mise-en-scène, but also Ventura’s quest — best seen in an extended elevator sequence, which was appropriately given the title Sweet Exorcism when it initially appeared in the 2013 omnibus film Centro Historico.”

In the Hollywood Reporter, Neil Young suggests that “the more the viewer is aware of his previous output, not to mention the mid-1970s history of Cabo Verde and Portugal, the more they’ll likely be able to appreciate and understand what’s going on in this example of what can safely be termed ‘post-narrative’ cinema.” Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn finds Horse Money “more subdued and cryptic than its predecessors, to the point where it might be more appropriately described as a cinematic tone poem.”

“The film was supposed to include another screenwriter, a composer and actor who I met, shot with a little bit, just a few minutes,” Costa tells Neil Bahadur in a Film Comment interview. “He was supposed to write two or three musical scenes. And then he died…. It was Gil Scott-Heron.”

Horse Money is screening in the Wavelengths program in Toronto and will then head to the New York Film Festival next month.

Update: Daniel Kasman replies to Croce in the Notebook: “How come, Fernando, Pedro Costa has been working with such affecting ingenuity in digital cinema for all these years and yet we’ve barely seen the effects of his radical, politicized cinematic poetry perpetuate out in the world?… Since working in the digital medium, Costa has always pointed a new, deeply moving way that looks like nothing else out there, but why is the path behind him so empty?”

Update, 11/3: For Twitch, Patrick Holzapfel talks with Costa about John Ford and more.

2014 Indexes: Locarno + Toronto. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.