Director, screenwriter, producer, actor Martin Scorsese, tireless advocate of film preservation, founder of the Film Foundation and the World Cinema Foundation, is 70 today. Mary Pat Kelly’s 1991 book Martin Scorsese: A Journey features two forewords. Michael Powell’s was written shortly before his death in 1990, and in it, he declares that Scorsese’s “only just started!… The great sermons are to come. We are going to see many more. We are going to see the hearts of men laid bare. We are going to be shown what waits for us on the other side of the wall called convention. We are going to learn a very great deal.”

The other forward is by Steven Spielberg: “Both of us make movies that provoke strong reactions. Movies that make an audience respond. The difference is that Marty does all this on his own terms. He doesn’t fret about what’s going to ‘work,’ or not ‘work,’ for an audience. His concern is what’s true to the characters and what’s right for their feelings. If he can work that out—and he always does—then he goes right ahead, and lets the audience catch up with him. And if they don’t, Marty doesn’t wait around for them. I admire that, too. Maybe I even envy it a little.”

“Scorsese seems to know hell like the back of his hand, and he doesn’t find it amusing,” wrote Jonathan Rosenbaum in 1988, reviewing The Last Temptation of Christ for the Chicago Reader. “Scorsese plunges into the unknown without a return address, riddled with guilt and conflict, and what emerges is both an authentic and an authentically upsetting struggle, illuminating yet perpetually unresolved.” See also Rosenbaum’s 1996 revisitation of Taxi Driver (1976), Scorsese’s “most morally and ideologically problematic” film.

“The Scorsese/De Niro relationship has proved one of the most fruitful director/star collaborations in the history of the cinema,” wrote Robin Wood (exactly when is hard to say; at any rate, you’ll find the piece at Film Reference). “[I]ts ramifications are extremely complex. De Niro’s star image is central to this, poised as it is on the borderline between ‘star’ and ‘actor’—the charismatic personality, the self-effacing impersonator of diverse characters. It is this ambiguity in the De Niro star persona that makes possible the ambiguity in the actor/director relationship: the degree to which Scorsese identifies with the characters De Niro plays, versus the degree to which he distances himself from them. It is this tension (communicated very directly to the spectator) between identification and repudiation that gives the films their uniquely disturbing quality.” One more snippet: “King of Comedy [1983] may seem at first sight a slighter work than its two predecessors [the two Wood has just addressed are New York, New York (1977) and Raging Bull (1980)], but its implications are no less radical and subversive: it is one of the most complete statements about the emotional and spiritual bankruptcy of patriarchal capitalism today that the cinema has given us.”

Speaking of which, in 1988, in a talk published in The Act of Seeing, Wim Wenders called King of Comedy “the most important and most misunderstood American film in the last ten years; it’s shown far too rarely, and… the scathing reception it got from the American media (resulting in the film’s failure at the box office) made me hopping mad. What this film offers is a radical critique of the American concept of entertainment.”

In his 2002 entry into Senses of Cinema‘s Great Directors database, Marc Raymond emphasizes the “split between reality and artifice in all his major films, combining realistic elements such as Method acting, detailed renderings of specific times and places and nonlinear plots, with expressionistic techniques such as rhythmic editing, slow-motion cinematography and non-diegetic sound effects.”

“The director’s currently hard at work on his fourth collaboration with Leonardo DiCaprio, the financial world drama The Wolf of Wall Street,” notes Oliver Lyttelton at the Playlist, “but as he enters his eighth decade, we wanted to pay tribute to the master by picking out five of his most underrated movies from across his career.”

If you’ve got all weekend to spend with Scorsese, I refer you to Catherine Grant‘s amazing collection of “mostly academic, and all great quality, studies of the work” at Film Studies for Free. And for yet more, turn to They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They?

Salutes in the German papers today come from Daniel Kothenschulte (Berliner Zeitung), Verena Lueken (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung), and Rainer Rother (Tagesspiegel).

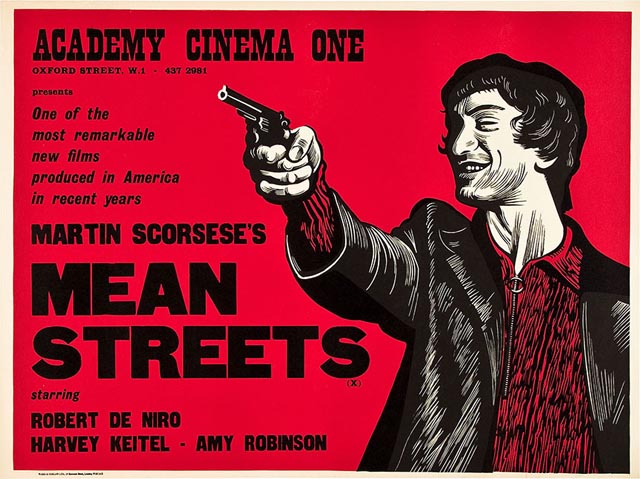

Poster for Mean Streets (1973) via Adrian Curry.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.