We can argue about whether or not 2013 really does mark the 100th anniversary of Indian cinema, but if the celebration is even partly responsible for the restoration and revival of the work of Satyajit Ray, bring it on. Today sees the opening of a two-part retrospective of Ray’s work at BFI Southbank in London, following a presentation of Charulata (The Lonely Wife, 1964) in Cannes. Criterion will be releasing Charulata as well as The Big City (1963) on DVD and Blu-ray next week, and restorations of Mahapurush (The Holy Man) and Kapurush (The Coward), both from 1965, will be screened in Venice in the Classics program. And on September 6, the Academy will present new prints of the Apu Trilogy in Los Angeles.

“The key to understanding the appeal of Satyajit Ray’s body of work,” writes Andrew Robinson, introducing the BFI’s season, “is that the director himself, though intimately rooted in Bengal, was also immersed in western culture: European and Hollywood films, of course, but also literature, art and music…. Born in Calcutta in 1921, Ray was educated in both Bengali and English, and studied for a fine arts degree, which he abandoned for a job as a commercial artist in advertising. As a filmmaker, Ray was entirely self-educated, except for a brief period helping Jean Renoir, who had come from Hollywood to make The River. The strongest influence on his first film, Pather Panchali, was seeing the neo-realist classic, Bicycle Thieves, in London in 1950: ‘It gored me,’ said Ray.”

Pather Panchali: A Living Resonance (2007)

“Other Indian directors had done valuable work before Pather Panchali, Ray’s first film, appeared in 1955,” writes Amit Chaudhuri in the Financial Times. In Bengal, “there was Bimal Roy’s exceptional leftwing parable Udayer Pathey (1944), and Pramathesh Barua’s wryly sophisticated comedy Rajat Jayanti (1939). And not long after Ray made that first masterpiece, there emerged a completely different—mythopoeic, occasionally over the top—sensibility in Ritwik Ghatak, an equally great filmmaker. But it’s undeniable that all Bengali and Indian cinema was changed after the release of Pather Panchali; not just with Ghatak, who saw it and altered course from his beginnings in socialist melodrama, but also Guru Dutt, the most gifted artist of popular Hindi cinema, who began to look at his craft anew. Even Iranian film—especially Abbas Kiarostami—bears the imprimatur of Ray’s legacy, especially his preoccupation with the commonplace, the everyday, and the child.”

“Lauded by the likes of Kurosawa and Scorsese, Ray made more than 35 films and received a lifetime achievement Oscar shortly before his death in 1992,” writes Sameer Rahim in the Telegraph. “Although his name is well known in Bengal, in India his work has not been especially influential (the all-singing and dancing Bollywood behemoth has long since seen him off). In the West, Ray’s films are more talked about than watched,” but Rahim is hoping the BFI retrospective will change all that. He notes, too, that Ray’s own life changed in 1949 when he worked with Renoir, who “encouraged him to ignore Hollywood and fulfill his own vision. Ray would acknowledge later that he had been ‘subconsciously… paying tribute to Renoir throughout my film-making career.'”

Ray’s films “begin with extended close-ups of rotating fans, or disrupted exam invigilations shown for so long they become unsettling,” writes Aditya Chakrabortty in the Guardian. “None of these quirks or details were accidental. Scripts were written by him, music was composed by him. The sets and costumes and design of posters: all were his. Ray’s biographer Andrew Robinson recalls visiting the director’s flat to find him ‘discussing the exact kind of button required by one of his costume designs with a member of his production team.'”

Roshan Kumari in The Music Room

The BFI’s Samuel Wigley spotlights “five essential films” with notes and selections from the scores to listen to: Pather Panchali (1955), of course; The Music Room (1958), “a great film to rank with The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) or The Leopard (1963) about grand old men whose ways are being eclipsed by passing time”; The Big City; Charulata; and Days and Nights in the Forest (1970), “a tribute to Renoir’s classic Partie de campagne (1936).”

Dave Calhoun in Time Out on The Big City: “Ray’s style is direct, realist and sympathetic, and only in the closing moments does he pull back to show the wider city. Before then, his eye is firmly and compassionately on the feelings and behavior of his various strongly drawn characters.”

Meantime, the Guardian‘s posted a gallery of posters for Ray’s films.

Updates, 8/16: The Big City is “an utterly absorbing and moving drama about the changing worlds of work and home in 1950s India, and a hymn to uxorious love acted with lightness, intelligence and wit,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw. David Jenkins in Little White Lies: “Arati (Madhabi Mukherjee) and Subrata (Anil Chatterjee) are a conventional, conservative, educated couple living on a shoestring among the bustle and burr of 1960s Calcutta—very much a city on the make. His paycheck pays for the kids’ tuition fees, the livelihoods of her (now broke) parents, plus any and all household expenditures. As a way to allay some of the strain from his purse strings, Subrata grants Arati permission to accept a job as a door-to-door salesgirl for a knitting machine company. In a similar fashion to George Cukor classic, A Star is Born, it’s not long before the family gender roles are reversed and the happy couple soon succumb to bouts of violence, jealousy and depression.”

Charulata “sees Ray trading the realist style of his earlier work for a sophisticated formalism on a par with that of Max Ophüls,” writes Jake Cole in Slant. “Not as ornate as the expat German, Ray nevertheless reflects Ophüls’s ability to delineate power structures, personal relationships, and desires through camera movement and placement, and how nominally mirrored shots communicate vastly different moods.”

Updates, 8/18: The Observer‘s Philip French on The Big City: “It was Ray’s first movie to be set entirely in his native Calcutta, and like his two later movies set in the business world of that city—Company Limited (1971) and The Middleman (1975)—it reflects his admiration for Dickens. This initially came from being a pupil of the great left-wing British Victorian scholar Humphry House at Calcutta’s Presidency college in the late 1930s. Ray’s Calcutta is a bustling Dickensian city of disappointment and hope, of new possibilities and old temptations, of entrepreneurs seizing opportunities in a changing society, of exploitation and cruelty, of major gulfs between poor and rich, of a burgeoning middle class 20 years after Indian independence, of bank failures that leave investors penniless.”

More from Tim Robey in the Telegraph: “Just when you think it’s heading for a regulation melodramatic ending, it springs a gloriously philosophical one instead.”

“I knew Ray well,” writes Derek Malcolm in the Evening Standard, “and it was easy to understand why some found him arrogant. A tall man—half a foot above most fellow Bengalis and much less forthcoming, largely because of shyness — he couldn’t abide sycophants, and there were always a lot of them about. The fact that he studied American and European films, music and art as much as Indian culture, particularly the great writer Rabindranath Tagore, also made some suspicious. He was neither fully integrated with Western nor Indian culture in the eyes of his detractors; how could Charulata, one of his best films, they complained, have been inspired by Mozart’s operas? They were, of course, utterly wrong. His films were totally Indian and regularly broke new ground.”

Viewing (1’26”). At the BFI, Salman Rushdie explains why he believes Pather Panchali is the greatest film ever made.

Updates, 8/20: “Like many of Ray’s greatest films, The Big City is ultimately a study of individuals negotiating social change, in this case the major shift that occurred in Bengal in the 1950s when increasing numbers of middle-class housewives began to take up jobs,” writes Chandak Sengoopta for Criterion. It’s “also pioneering in its treatment of race and racial discrimination, themes rarely featured in Indian films and almost never, according to critic Dipendu Chakrabarty, in association with gender issues…. Ray’s style in The Big City, remarked critic Eric Rhode in 1976, recalls the realism of 19th-century European novelists. Characters are ‘both individuals and social types’; the city’s economic and class structure is more important to the narrative than its scenic qualities; and even ‘the most trivial of objects are made dynamically essential to the plot.'”

Both Criterion Blu-rays “come loaded with interviews,” notes Noel Murray at the Dissolve: “new ones with Madhabi Mukherjee and Soumitra Chatterjee; vintage ones with Ray; multiple ones with academics and historians who speak to Ray’s depiction of women and class. The impression of Ray in these interviews is of a kind-hearted, curious, studious man. (‘He was magnanimous as the sky, and serious as a mountain,’ Mukherjee says.) But Ray gives a somewhat different impression of himself—or at least of someone like himself—in the most significant extra, the 1965 film The Coward. A 70-minute chamber drama (available on the Big City disc), The Coward follows a screenwriter named ‘Roy’ (Chatterjee) who has a surprise encounter with a woman he once jilted (Mukherjee) when his car breaks down in the country. In the film, Ray shows far more sympathy to the farmer’s wife than to the fairly condescending filmmaker, because Ray often saw the world most clearly through eyes other than his own.”

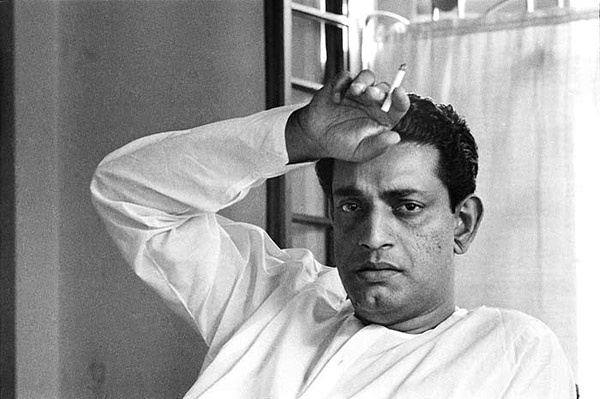

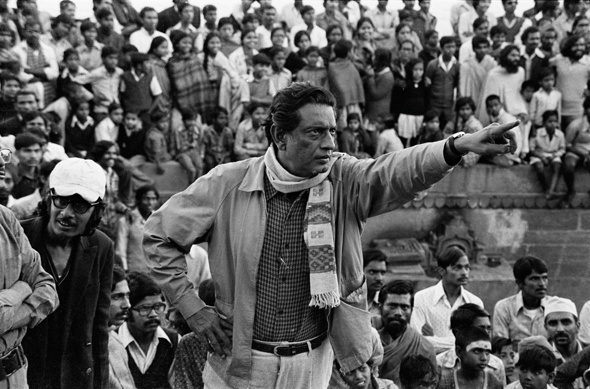

For the BFI, Andrew Robinson introduces a collection of photographs Nemai Ghosh shot of Ray from 1968 through 1992: “Ray trusted Ghosh, who worked for the love of Ray’s films, not for money, until 1982; indeed, Ghosh’s obsession with Ray swallowed up the last rupee of his savings. So he was allowed to become a fly on the wall during all stages of the process of filmmaking.”

Satyajit Ray Restored, a series at the Aero Theatre in Los Angeles, opens on September 12 and runs through October 21. Susan King has an overview in the Times.

“Charulata (1964), often rated the director’s finest film—and the one that, when pressed, he would name as his own personal favorite: ‘It’s the one with the fewest flaws’—is adapted from Tagore’s 1901 novella Nastanirh (The Broken Nest),” writes Philip Kemp for Criterion. “It’s widely believed that the story was inspired by Tagore’s relationship with his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi, who committed suicide in 1884 for reasons that have never been fully explained. Kadambari, like Charulata, was beautiful, intelligent, and a gifted writer, and toward the end of his life, Tagore admitted that the hundreds of haunting portraits of women that he painted in his later years were inspired by memories of her…. From its lyrical high point in the garden scene, the mood of Charulata gradually if imperceptibly darkens, moving toward emotional conflict and, eventually, desolation.”

Update, 8/21: The Big City and Charulata “make a compelling case for the legendary Bengali director as one of cinema’s great feminist storytellers,” argues Paul Anthony Johnson at Cinespect. “[T]hey’re also among the most devastatingly perceptive movies ever made about marriage, conveying the terrifying fragility of human affection in the face of bad luck and good intentions.”

Updates, 8/23: “One could label Ray a neorealist, but it’s important to note how the director never allows the plainspoken tone of his film to soften his style or fetishize dullness in the name of art or honesty,” writes Chris Cabin, reviewing The Big City at Slant.

And Sean Axmaker for MSN: “The conclusion, though a little too pat compared to Charulata and other Ray films, is buoyed by hope and conscience and a devotion to the characters we have lived with for the last two hours. His compassion trumps all.”

Updates, 8/29: “In a just world,” writes Mike D’Angelo at the AV Club, “Madhabi Mukherjee would have the same iconic presence in cinema history (for an American audience) as European contemporaries like Jeanne Moreau, Catherine Deneuve, and Giulietta Masina. Deneuve is perhaps the strongest parallel—both women are so stunningly beautiful that it’s easy to overlook the shrewd intelligence that underlies their every move. Mukherjee worked with such esteemed directors as Ritwik Ghatak (The Golden Thread) and Mrinal Sen (Calcutta 71), but she remains best known for the three films she made with the great Satyajit Ray, two of which are being released by Criterion this week.” And he goes on, of course, to review Charulata and The Big City.

Meantime, Criterion’s posted a slide show on these two features with notes from Abbey Lustgarten.

Update, 8/30: “In 1992,” writes Doug Cummings in the LA Weekly, “when renowned Indian filmmaker Satyajit Ray was presented a lifetime achievement Oscar on his deathbed, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences couldn’t find enough prints to assemble a tribute reel. ‘Literally,’ says Academy Film Archive director Mike Pogorzelski, ‘the only prints that were in the U.S. were so battered and worn, they weren’t good enough for the telecast.’ Since then, the archive has been restoring roughly a Ray feature per year, and all 18 features and one short restored to date will screen Sept. 6 to Oct. 21 at the Aero Theatre and at the Academy.”

Update, 9/4: For the BFI, Andrew Robinson has compiled an interview from a long series of conversations he had with Ray while researching his biography.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.