“The received wisdom on Jacques Rivette, for supporters and detractors alike, is that his is a cinema of endurance,” wrote Keith Uhlich in Slant on the occasion of a “near-complete” retrospective in New York in 2006. “Rivette’s films don’t so much move as imperceptibly invade.” His introduction leads to his capsule reviews of Le Coup du Berger (1956), Paris Belongs to Us (1960), The Nun (1966), L’Amour Fou (1969), Out 1 (1971) , Céline and Julie Go Boating (1974), Le Pont du Nord (1981), Merry-Go-Round (1981), Love on the Ground (1984), Hurlevent (1985), and Le Belle Noiseuse (1991), plus Ed Gonzalez on Va Savoir (2001), Fernando F. Croce on The Duchess of Langeais (2007), and Andrew Schenker on Around a Small Mountain (2009).

In Senses of Cinema‘s entry on Rivette, who turns 85 today, Saul Austerlitz argues that the oeuvre “may be the most spectacular of all the French New Wave generation.” Born in Rouen, he moved to Paris, where, in 1950, “he became involved with the Ciné-Club du Quartier Latin, and contributed articles to its bulletin, the Gazette du Cinema, edited by Eric Rohmer. During this period, he also directed his first short films, Aux Quatre Coins (1950), Le Quadrille (1950), and Le Divertissement (1952). Rivette’s friendship with Rohmer led him to the new film journal Cahiers du cinéma, edited by Andre Bazin and Jacques Doniol-Valcroze. During the years of 1952 and 1953, the core of the Cahiers group formed, anchored around the quintet of Rivette, Rohmer, Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and Claude Chabrol…. Rivette had worked as an assistant to Jacques Becker and Jean Renoir, and when Truffaut and Rohmer made their first shorts, he served as their cameraman. In 1958, Rivette—before Truffaut, Godard or Rohmer and second only to Chabrol—began shooting his first feature-length film.”

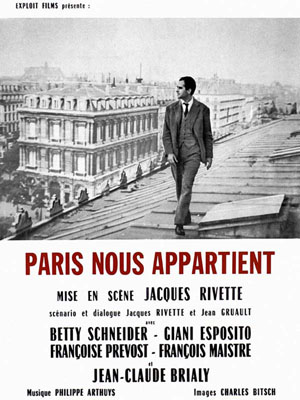

Introducing an extraordinarily engaging interview with Rivette that he, Gilbert Adair, and Lauren Sedofsky conducted for a 1974 issue of Film Comment, Jonathan Rosenbaum writes of that first feature, Paris Nous Appartient (Paris Belongs to Us): “An anguished portrayal of a milieu of outsiders—an impoverished but ambitious theater group, a paranoiac American expatriate, and other marginal figures occupying seedy one-room flats—Paris is the most oppressively Langian of Rivette’s films, oscillating between poetic visions of grandeur (cf. the title) and alienated nightmares of despair (reflected in the opening epigraph, ‘Paris belongs to no one’)…. Every Rivette film has its Eisenstein/Lang/Hitchcock side—an impulse to design and plot, dominate and control—and its Renoir/Hawks/Rossellini side: an impulse to ‘let things go,’ open one’s self up to the play and power of other personalities, and watch what happens. Rivette is explicit about this distinction in the last part of our interview, but all his films display some measure of both aloofness and interaction.”

Rivette’s body of work may remain, relative to that of other French New Wave directors, under-explored, but certainly not under-appreciated. Dan Callahan in the L just the other day: “Stage director Doris Mirescu is using three of his movies, L’Amour fou (1969), Out 1 (1971) and Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974), as the bases for a yearlong multimedia theater event entitled 3 by Rivette—three plays that the troupe Dangerous Ground will perform at the Brick Theatre, starting with L’Amour fou (through March 10). ‘For me, all three films are linked in mysterious ways,’ Mirescu says. ‘They have common themes: theater, literature, love, time, revolution, resistance, freedom.'”

Interestingly, reviewing Criterion’s release of Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin’s Chronicle of a Summer (1960), out this week, the New Yorker‘s Richard Brody notes that Rivette pops up in one of the extras, seen in the office of Cahiers du Cinéma “passionately discussing one of the movies of the moment, Michelangelo Antonioni‘s L’Avventura: ‘It’s everything I hate in films taken to such an extreme that it’s not bad.’ His interlocutor, Lydie Doniol-Valcroze, asks what he hates: ‘Literature, aestheticism, pretentiousness, sentimentalism.’ He adds, ‘I’ll need to see it for a third time to know,’ but that, overall, ‘I prefer virile filmmakers.'”

“I guess I like a lot of directors,” Rivette told Frédéric Bonnaud in an interview I can’t seem to find a date for (it was translated by Kent Jones). “If you see a lot, you can choose the films you want to be influenced by. Sometimes the choice isn’t conscious, but there are some things in life that are far more powerful than we are, and that affect us profoundly. If I’m influenced by Hitchcock, Rossellini or Renoir without realizing it, so much the better.” What follows are his quick takes on films by Rossellini, Melville, Lang, Hawks, Bresson, Pialat, Minnelli, Buñuel, David Lynch, and many more.

We can’t wrap without mentioning and recommending a visit to the amazing labor of love Order of the Exile: Concerning the Films of Jacques Rivette, a vast collection of reviews, essays, and interviews. If you haven’t stumbled across it before, be glad the weekend’s around the corner.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.