“Actor Peter O’Toole, who starred in Sir David Lean’s 1962 film classic Lawrence of Arabia, has died aged 81,” reports the BBC. Robert Booth for the Guardian: “O’Toole announced last year he was stopping acting saying: ‘I bid the profession a dry-eyed and profoundly grateful farewell.’ He said his career on stage and screen fulfilled him emotionally and financially, bringing him together ‘with fine people, good companions with whom I’ve shared the inevitable lot of all actors: flops and hits.'”

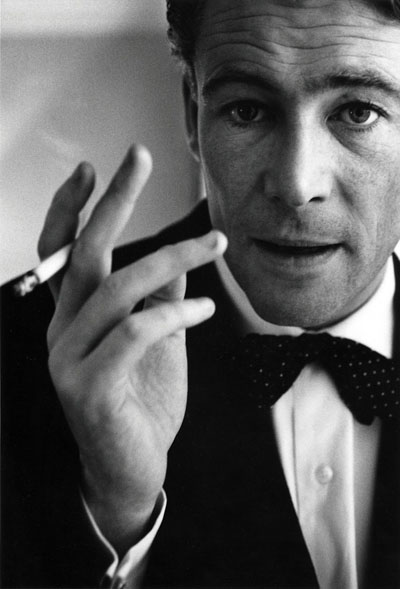

“For O’Toole’s admirers, their favorite year will always be 1962, when he embodied in Lawrence the fascinating ambiguities of a man terrified by his own moral passion,” writes Jasper Rees at the Arts Desk. “His last truly great performance in a film was in The Last Emperor in 1987. Since then there had been emperors, plus kings, dukes, lords and knights. But his turn in the spotlight seemed to have been and gone…. Coincidentally How to Steal a Million [1966] was on soon after I met him, and even in a frothy romantic comedy opposite Audrey Hepburn, William Wyler knew exactly how to introduce his leading man: with a close-up of those preternaturally blue eyes. They were the only remnant of the Adonis who freed Arabia, and their owner was inclined to make light of them.”

Peter O’Toole, who was 81, roared in the 60s, with “career-defining performances,” as TCM calls them, “in Becket (1964), Lord Jim (1965), and The Lion in Winter (1968). Behind the scenes, of course, O’Toole cultivated a well-deserved reputation as a hard-drinking, two-fisted hell-raiser alongside his equally rough-and-tumble compatriots Richard Harris, Oliver Reed and Richard Burton.”

Nathan Southern for the All Movie Guide: “The early 1970s were equally electric for O’Toole, with the highlight undoubtedly being his characterization of a delusional mental patient who thinks he’s alternately Jesus Christ and Jack the Ripper in The Ruling Class (1972), Peter Medak’s outrageous farce on the ‘deific’ pretensions of British royalty. That gleaned O’Toole a fifth Oscar nomination; Jay Cocks, of Time Magazine called his performance one ‘of such intensity that it will haunt memory. He is funny, disturbing, and finally, devastating.'”

Back to TCM: “Following more acclaim for The Stunt Man (1980) and My Favorite Year (1982), O’Toole receded into the background for supporting roles in The Last Emperor (1987), King Ralph (1991), and Joan of Arc (CBS, 1999). He went on to play Greek king Priam in Troy (2005) before earning his eighth and final Oscar nomination for his leading role in Venus (2006).”

Updates: “Seamus Peter O’Toole was born Aug. 2, 1932, the son of Irish bookie Patrick ‘Spats’ O’Toole and his wife Constance,” reports Gregory Katz for the AP. “There is some question about whether Peter was born in Connemara, Ireland, or in Leeds, northern England, where he grew up. After a teenage foray into journalism at the Yorkshire Evening Post and national military service with the navy, young O’Toole auditioned for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and won a scholarship…. The image of the renegade hell-raiser stayed with O’Toole for decades, although he gave up drinking in 1975 following serious health problems and major surgery. He did not, however, give up smoking unfiltered Gauloises cigarettes in an ebony holder. That and his penchant for green socks, voluminous overcoats and trailing scarves lent him a rakish air and suited his fondness for drama in the old-fashioned ‘bravura’ manner.”

The Playlist‘s Oliver Lyttelton looks back on five great performances: Lawrence, of course. The Ruling Class, wherein ” there’s a performance—or more accurately, several performances—from O’Toole that comes close to being his career best. He’s sweet-natured, yet a little narcissitic when in holy mode, and positively blood-chilling once he gets his personality shift, and deftly navigates the tricky tone throughout.” My Favorite Year and Venus. And Anton Ego, the food critic in Ratatouille (2007), “the emotional heart of the film, his mind changed by a Proustian flashback caused by rat Remy’s cooking, and O’Toole gets a killer monologue by the end, both skewering and justifying the art of criticism.”

Viewing. O’Toole and Orson Welles discuss Hamlet in 1963, parts 1, 2, and 3. Xan Brooks collects more clips from an array of performances for the Guardian.

Richard Burton once called O’Toole “the most original actor to come out of Britain since the war,” with “something odd, mystical and deeply disturbing” in his work, notes Benedict Nightingale in the New York Times: “Some critics called him the next Laurence Olivier. As a young actor Mr. O’Toole displayed an authority that the critic Kenneth Tynan said ‘may presage greatness.’ In 1958 the director Peter Hall called Mr. O’Toole’s Hamlet in a London production ‘electrifying’ and ‘unendurably exciting’—a display of ‘animal magnetism and danger which proclaimed the real thing.’ He showed those strengths somewhat erratically, however; for all his accolades and his box-office success, there was a lingering note of unfulfilled promise in Mr. O’Toole.”

David Thomson for the Guardian: “O’Toole was plainly fascinated by ham acting and theatrical travesty—in one of his most entertaining films, My Favorite Year (1982), he played an actor, Alan Swann, a swashbuckler in the tradition of Errol Flynn. It earned him his seventh Oscar nomination but he lost to Ben Kingsley for Gandhi. Seven Oscar failures was a rueful glory he shared for a while with his old pal, Richard Burton. In 2003, he was awarded an honorary Oscar. He accepted but did not agree to be finished, There would be an eighth ‘failure’—his resplendent record.” Overall, O’Toole’s “was an utterly unpredictable course for the actor whose Lawrence and Hamlet had seemed to command the world.”

O’Toole “had a movie career that lasted over 50 years, with one signature role after another,” writes Noel Murray at the Dissolve: “T.E. Lawrence, Henry II (times two), Arthur Chipping, Jack Gurney, Eli Cross, Allan Swann, and his last major performance as an ailing actor named Maurice in the 2006 dramedy Venus. What almost all of those characters have in common is a combination of assuredness and unpredictability. They all seem to know exactly what they’re doing, even though they often baffle and exhaust everyone around them…. O’Toole was also an excellent writer, and the two volumes of his memoirs Loitering With Intent present him as personable and witty… The literary O’Toole is different from the men he played on-screen, and presents a fuller picture of a man who was beloved by many of his co-stars. But even the charming O’Toole of his autobiographies and talk show appearances maintained an air of mystery. O’Toole always seemed so much more intense than other human beings: handsomer, more in touch with his emotions, and perpetually lost in thoughts that the rest of us could never fully comprehend.”

Updates, 12/16: “Perhaps there were other actors as beautiful as Peter O’Toole in his 60s pomp,” writes the Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw, “but surely no one had such mesmeric eyes—the eyes of a seducer, a visionary or an anchorite, a sinner or a saint. That long, handsome face compellingly suggested something intelligent and romantic. But there was also something tortured there, sexually wayward and dysfunctional, something that no O’Toole character would ever entirely own up to.”

“He was possibly the most charismatic, handsome, and gifted of his acting peers, remarkable when you consider that his fellow actors in the 1954 graduating class of London’s Royal Academy of Dramatic Art included Richard Harris, Albert Finney, and Alan Bates.” The Boston Globe‘s Ty Burr: “Richard Burton reveled in his fame; Finney used it, got bored, and became a character actor. But O’Toole made hesitancy his metier. His T. E. Lawrence is the hero terrified of what heroism may bring—a larger-than-life adventurer when seen from a distance, a tremulous blue-eyed existentialist when encountered up close. The tension, majesty, and sorrow of the performance came from some mysterious place between the two.”

In his obituary for Variety, Scott Foundas draws attention to O’Toole’s overlooked performance as “Spectator journalist Jeffrey Bernard in the play Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, which opened on the West End in 1989 and was subsequently filmed for television. The title, fittingly, referred to the one-line apologia that would appear in place of Bernard’s ‘Low Life’ column on those (frequent) occasions when he was too drunk, hungover or otherwise incapacitated to produce it. Bernard was among O’Toole’s favorite projects—one he insisted on presenting in 2002 at the Telluride Film Festival, where he was feted with a career tribute.”

And the Chicago Sun-Times has reposted Roger Ebert‘s account of his discussion of Lawrence with O’Toole at Telluride that year.

Farran Nehme posts delicious excerpts from biographies, diaries, and memoirs as well as some of O’Toole’s best lines.

The BBC collects tributes from Michael Gambon, John Standing, Irish President Michael D. Higgins, British Prime Minister David Cameron, film critic Barry Norman, Stephen Fry, and more, while HitFix reposts tweets from Neil Patrick Harris, Kevin Smith, Tom Hiddleston, and many others.

“I’m sad to bid thee farewell, Peter O’Toole,” writes Tim Lucas, “but the frank truth of the matter is that you were always a mystery to me. I’ve always liked the cut of you, enjoyed you immensely on talk shows; you were always as sharp as a stoned tack, but for some reason you had the most uncanny knack for selecting projects that weren’t geared to grab me. Forgive my candor, old bean, but it’s true, lamentably true…. But what a face! What a voice! What an amazing character you were!”

“During the filming of Venus over the Christmas break, Peter O’Toole fell and broke a hip. When he came back to us a heroic three weeks later, hip replaced, he needed every ounce of his considerable resolution and grit to get through each agonizingly painful day.” The Guardian posts entries from director Roger Michell‘s diary.

When Lawrence was restored and re-released in 1989, Jonathan Rosenbaum raved, and he’s just now posted that Chicago Reader review.

Anthony Lane for the New Yorker: “Like many stars, he was actually twin stars, fused together; within his nature, the gentleman cohabited with the fearful rake, just as, within his Lawrence, something fey and dreamy, bordering dangerously on the camp, consorted with the unappeased ferocity of the warrior. Both facets shone in his sapphire stare. And that voice! By what miracle of instinct did Lean manage to cast a man who sounded, even before he reached the desert, as though his words had been naturally sanded?”

“I think that what he liked best was to go back and forth between feminine delicacy and masculine roaring, sometimes in the same role,” writes David Edelstein. Also for Vulture, Bilge Ebiri lists “12 of Peter O’Toole’s Best (and Most Underrated) Performances.”

O’Toole “had begun at such a height that the rest of his career was almost bound to be anticlimactic—a half-century schuss from the top of Everest.” Time‘s Richard Corliss: “The trip was exciting, the view splendid. Even the spills were fun.”

“I met him three or four times in the course of his long career, and more than once the occasion was for him to discuss some forgettable movie,” recalls the Telegraph‘s David Gritten. “But strikingly, his colleagues—even producers, who have a sharp eye for a financial investment being frittered away on set—only had appreciative, affectionate words for him: they called him determined, co-operative and hard-working. O’Toole was an unpredictable character, yet utterly professional.”

Updates, 12/20: “Of all the many people I’ve written about in 60 years of being published, Peter O’Toole remains my favorite,” writes Gay Talese, introducing the republication of his profile of O’Toole for the August 1963 issue of Esquire. “What struck me as unique about him, as a celebrity and enormously talented artist, was that fact that while he responded candidly to my questions, he had questions of his own. He was not only the most intellectually curious person I’ve ever interviewed, but he interviewed me.”

“O’Toole was elegantly at home in the broth of silly brio that was pre-counterculture 1960s moviemaking,” writes Tom Carson in the American Prospect. “He’s fetchingly self-amused as the womanizer Sellers is psychoanalyzing in ’65’s What’s New, Pussycat?—based on Warren Beatty’s amorous career, incidentally, and originally slotted to star Beatty himself until the actor tangled with the young Woody Allen over the script. Even in an ostensibly solemn prestige picture like 1964’s Becket—based on Jean Anouilh’s play, and starring O’Toole as Henry II opposite Burton in the title role—you can tell how much he’s enjoying himself. Perhaps more remarkably, he’s energizing his co-star to do the same; as they vie to see who can extract the most irony and/or entertainment value from Anouilh’s faux-mordant, faux-profound dialogue, he and Burton are having a great time engaging in a cutting contest.”

“To meet O’Toole was to be thrilled, if bewildered, by the restless panache that managed to be life-affirming and self-destructive at the same time,” writes David Thomson for the New Republic. “He was not like the others. That may have been his cause all along, and there will be O’Toole stories long after respectable actors are forgotten.”

Aaron Cutler: “O’Toole lent incredible beauty and charisma to the demented figure of T.E. Lawrence—as he subsequently would to Henry II in Becket and in The Lion in Winter, as well as to the crazed power-mongerers in The Ruling Class and The Stunt Man—in order to suggest not just the charms of leaders, but also the great dangers of following them.”

Update, 12/26: “By 1962, the movies were still treating color as a special occasion—for musicals and massive spectacles.” Wesley Morris at Grantland: “O’Toole’s face qualified as a spectacle. In a film situated in the Arabian desert, eyes that blue were a double tease: hypnotic, yes, but mostly because they looked hydrating, two tablets of relief in a tall-drink-of-water body. By the time the movie is over, you don’t know whether to applaud or stick a straw in him…. There was an uncouth undercurrent with him that was exciting. It was as if he didn’t respect the material even as he acted up a storm. In Becket, his Henry II slouched upon the throne. In The Lion in Winter, opposite Katharine Hepburn, you’re nervous that his beard will fall off. But he would’ve kept going anyway.”

Update, 12/27: Joseph Wambaugh, the former Los Angeles police sergeant-turned-novelist, recalls the night in 1962 when his team stopped a cab that’d just “picked up two players from the stakeout address. When it was pulled over, both passengers jumped from the cab like it was on fire. Left behind on the back seat was a bag of pot and uppers—not much of a violation today but in those days a felony booking.” Those passengers were Lenny Bruce and Peter O’Toole—who talked the unlikely pair out of a potentially career-damaging arrest. An amusing story via Joe Leydon.

Update, 1/6: At Movie Morlocks, Kimberly Lindbergs shares “some fascinating facts and anecdotes about the early life of the tall and lanky handsome Irishman that can be found in one of my favorite books about Peter O’Toole and his acting compatriots, Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down: How One Generation of British Actors Changed the World by Robert Sellers.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.