Today being the actual 70th anniversary of the birth of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, I’ve updated the “Fassbinder @ 70” entry—and here, I thought I’d drop a note or two on Fassbinder NOW, the exhibition currently on view in Berlin through August 23.

Frankly, I was a little worried walking in because Pasolini Roma, also in the Martin-Gropius-Bau, had been a bit of a letdown. To be fair, the exhibition may have simply paled in comparison with P.P.P: Pier Paolo Pasolini, a stunner of a show I caught at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich in 2005. But when you’re confronted with clips projected onto the windshield of an old Fiat 1100 or a half-ass recreation of Pasolini and his mother’s arrival in Rome complete with train windows and sound effects, something’s off. It was all way too cute for Pasolini. Any exhibition about a filmmaker rather than a painter or sculptor will pose its own challenges, but you’d think it’d be hard to go wrong with Pasolini. The man painted, drew, wrote poetry and criticism, corresponded with Godard and Maria Callas, sparked trials and headlines and left behind reams of documentation and hours of recordings and footage every step of the way. The one impression you came away from Pasolini Roma with was clutter.

The curators of Fassbinder – NOW, a far superior show, have resisted the temptation to overstuff the building’s second floor. And the temptation must have been mighty. Again: 44 movies in 16 years. But the exhibition is an expertly balanced blend of paraphernalia—screenplays, notes and letters, RWF’s pinball machine and that famous leather jacket—and well-chosen, smartly juxtaposed clips as well as work by contemporary artists inspired by the films.

You’re greeted by a sort of foyer with a video wall playing clips from various interviews, reminders that, for all the scoffing, smirking and dismissive question-dodging you see all too often in documentaries on the New German Cinema of the late 60s, 70s and early 80s, Fassbinder could be an engaging and surprisingly earnest talker. He truly believed in what he was doing and that the films he was working on, often two or three at a time, as well as a good number of those being made by his German contemporaries—again, for all his infamous assholery, he could also surprise with his generosity—could stand well on their own up against the best of the films coming out at the time from France, Italy or Hollywood (the three bar-setters he mentions on more than a few occasions).

Of all the artifacts gathered in a single cavernous hall (except for another room devoted to the costumes designed by Barbara Baum, which, you know, fine—I’ll admit right off to being severely undereducated in that department), the most impressive to me is a giant chart, a grid of hundreds of tiny squares, a graph recording the day by day progress of the production of the 14-part television mini-series, Berlin Alexanderplatz (1980): which actors, crew members, props, etc., needed to be where when.

But the chart itself is only the half of it. Once he’d written the adaptation of Alfred Döblin’s 1929 novel, Fassbinder dictated into a recorder notes on each and every shot. A verbal storyboard. And he’d talk into that recorder sometimes three days at a stretch without sleeping. And you can listen to them. Slip on the headphones and you’ll hear, say, “Shot 4A. Medium closeup on Franz. Tilt up as he lifts his head.” It was his mother, the heroic Liselotte, who turned dozens and dozens of these hours into workable production notes. Fassbinder ran such an efficient set that the production, originally scheduled for just under 200 days, wrapped after just over 150.

Of the work by contemporary artists in the other rooms, the work at least partly responsible for the NOW in the exhibition’s title, it’s pretty hit-and-miss, but one piece, Runa Islam’s Garden, is outstanding. First, though, for background, we turn to Das fliegende Auge (The Flying Eye), a 2002 collection of interviews conducted by Tom Tykwer with cinematographer Michael Ballhaus. The translation’s mine, so the errors are, too:

Tom Tykwer: We can’t talk about Martha [1974] without bringing up your first 360-degree tracking shot, the first and still legendary Ballhaus Circle.

Michael Ballhaus: The moment in which Karlheinz Böhm and Margit Carstensen meet for the first time was to have been a key scene. And we wanted to make it immediately recognizable as such. So I came up with the idea of starting with her profile and moving around them in a semi-circle before landing on his profile—and all that as the two of them walk past each other. Fassbinder’s reaction was typical: “Why just a semi-circle? Why don’t we go all the way around them?” “Because the ground’s at a slight angle and the tracks would come into the frame. And besides, how would the actors get around the tracks?” “You let me worry about that, I’ll take care of it.” So we built a circle that opened up on one end, while the other side was thirty centimeter’s higher, to make up for the angle of the ground. And in the end, Böhm actually managed to step over the tracks.

TT: But still, that’s thirty centimeters.

MB: And you see it in the completed film, too. If you look closely, you can clearly make out how Böhm steps over the tracks. But all this still wasn’t enough for Fassbinder. He always wanted to push things a step further, so the two of them had to turn around each other one more round. That, of course, was the topper, pushing the effect to the max. The scene now has that sense of reeling rapture that we were after.

We were so excited about this 360-degree tracking shot that we used it again and again. It became my trademark and, eventually, it was one of the reasons that Scorsese took notice of me. When I was starting out in the U.S., I used a particularly extreme circling tracking shot in [James Foley’s] Reckless [1984].

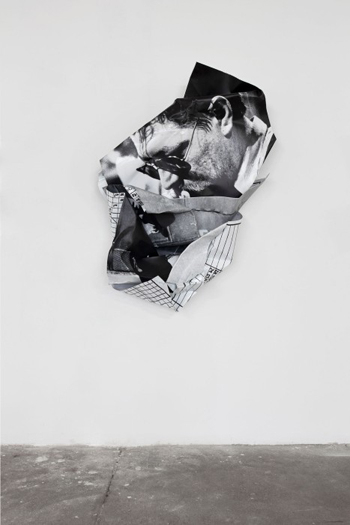

For her installation, Garden, Runa Islam has reconstructed this landmark 360-degree tracking shot. As you enter the darkened room, the first thing that strikes you is the sound: a projector, clicking away, 24 frames per second. A loop of 16mm color film is projected onto a translucent screen (so that you can watch both sides, albeit not simultaneously, of course) perpendicular to the wall—where black and white video shows us, side by side, the points of view of each of the actors. In the video, there’s no effort to hide the camera, the tracks, the focus-puller, etc.

Wherever you stand in the room, you can watch this thrillingly choreographed meeting through three separate yet synchronized lenses—the scene as we know it, in color; and his and her journeys across that courtyard, in black and white. To have the color “final scene” floating freely in the middle of the room and set at a 90-degree angle apart from the black and white POVs is to encourage the viewer to walk, to circle the center screen as the actors circle each other and to experience all this swirling movement in all its full, three-dimensional spatiality. The moment the actors’ faces are just inches from each other… It’s breathtaking.

P.S. Kevin B. Lee, I’ve got a hunch you’d really like Garden.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.