“For at least 20 years I’ve remembered John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966) with a feeling of clammy dread unique to that film, and recommended it to countless friends without ever quite working up the nerve to rewatch it myself,” begins Dana Stevens at Slate. “Sometimes the person I’m recommending it to will already know the movie, and they’ll get a wild look in their eyes for a moment and say ‘Oh my God, Seconds.'” With Criterion releasing a Blu-ray tomorrow “loaded with extras,” she’s finally revisited “this utterly sui generis, categorization-defying film, a horror-tinged thriller (or is it a sci-fi-inflected political parable?) about aging, alienation, and the American belief in starting over.”

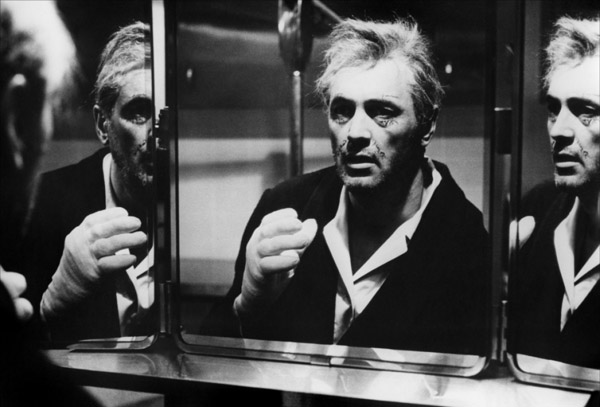

“Beginning with a tone-setting, spine-tingling Saul Bass title sequence and fiendishly shot by the late James Wong Howe in disorienting Dutch angles (sometimes aided by fish-eye lens and canted mirrors), this adaptation of a David Ely novel concerns a Twilight Zone-esque second chance for jaded middle-aged banker and husband Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph),” writes Aaron Hillis at Press Play. “After a stranger inexplicably hands him a scrap of paper with an address, vouched for by telephone from an old friend thought deceased, Arthur finds himself coerced by a shifty corporation into being ‘reborn.'”

Rock Hudson “portrays Antiochus ‘Tony’ Wilson, the hapless ‘after’ in the gruesomely elaborate before-and-after scheme that propels the genre-melding story,” adds Sheri Linden in the Los Angeles Times.

In 1966, Glenn Kenny was seven, and he recalls that Seconds “was a movie that intrigued my mom and a lot of friends her age because a) it was an unusual picture, a disturbing picture, but also a ‘modern’ picture, a picture about what was happening ‘now;’ and b) because its central conceit had an old person who hated his life undergoing a seemingly miraculous transformation into, well, Rock Hudson.” And “it is still to Hudson’s credit that when seen today his work in Seconds can live up to expectations that his actual audience didn’t even think to entertain in 1966…. Some sources say that he made the movie at around the time he was just beginning to share the reality of his life as a gay man with some of his friends; arguably, this dimension added some genuine depth to the who-am-I tortures his character puts himself through.”

“Seconds is, intentionally or not, a great movie about the closet,” writes Melissa Anderson for Artforum. “I am not the first to suggest this: Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (1992)—Mark Rappaport’s clever project in which a surrogate for the DL screen idol, the first major celebrity to die from AIDS, in 1985, narrates his own life from beyond the grave—uses clips from Hudson’s filmography, including Seconds, to demonstrate that his homosexuality was obvious all along. But Frankenheimer’s movie, in which Hudson doesn’t appear until the forty-minute mark, abounds with other queer signifiers—even if they are the result of what cinema scholar Patricia White has termed ‘retrospectatorship,’ of viewing the past from a contemporary position.”

“The final chapter in Frankenheimer’s informal ‘Paranoia Trilogy,’ (the other installments being The Manchurian Candidate and Seven Days in May), Seconds is the best and certainly the most enduringly resonant of the three, in part because it’s less of a political thriller than it is a resoundingly human one, less concerned with power than it is hope, regret and resignation,” writes David Ehrlich at Film.com. “A bleak reappraisal of The American Dream, Seconds unfolds like a bitter cocktail of Mad Men and David Fincher’s The Game, and the decades by which it anticipated those two reference works should be seen as a testament to how urgently unafraid Frankenheimer’s film was to tear away the gauze from the raw wounds that underlie our culture, the quiet fissures in our lives that western civilization perpetuates by promising to heal.”

Writing for Esquire (and via Critics Round Up), Calum Marsh notes that Mad Men “has spent six seasons trying to sell us the idea that our pursuit of material happiness is a crap deal, but in under two hours, Seconds tells you that even if it were possible to start fresh and have anything you want, you’d still be fked. That’s terrifying.”

Meantime, Bill Ryan‘s conducted an interesting experiment, interweaving paragraphs on Seconds with others on David Cronenberg’s The Fly (1986).

Updates, 8/14: Criterion’s posted David Sterritt‘s essay: “Frankenheimer had a gift for capturing the zeitgeist, and in the first two installments of his paranoia trilogy, he had already taken on some of postwar America’s most emotionally charged topics: brainwashing, commie bashing, and political assassination in The Manchurian Candidate (1962), about a man hypnotically programmed to kill, and then nuclear dread, Cold War anxiety, and neofascist skullduggery in Seven Days in May (1964), about a military plot to seize the American government. Seconds cuts even closer to the bone, exposing the precariousness of the American dream through a vertiginous blend of genre elements: horror, noir, and science fiction collide with suspense worthy of Hitchcock, outrageousness worthy of Kafka, and an acid critique of American capitalism.”

“The film tells the story of a man who tries to change his identity, but the elasticity of science isn’t matched by the elasticity of consciousness,” writes Scott Tobias at the Dissolve. “For an individual to truly change, without leaving any psychological residue behind, is impossible—to quote Confucius via The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai, ‘No matter where you go, there you are.'”

Josef Braun: “The collective desire for renewal at work in Seconds had been made into story before—there is some crossover between it and Ray Bradbury’s ‘Marionettes Inc.’—but Ely’s exploration of this perhaps specifically American idea of total self-reinvention took this desire to a sinister extreme. The film perfectly synthesizes the novel’s trajectory with the tools of cinema.”

Update, 8/16: James Wong Howe’s cinematography, “utilizing fish-eye lenses, canted camera angles, and a variety of Manhattan locations and studio interiors that run the visual gamut from documentary-like spontaneity to claustrophobic and agoraphobic effects, [evokes] The Trial and the work of Orson Welles in general,” finds Bill Weber at Slant.

Update, 8/23: “Seconds‘ soul,” writes Chuck Stephens for Criterion, “lies in the ways its story of reinvented identities and ‘naming names’ for ‘the Corporation’ parallel the crushing anxieties of the Communist witch hunts of the Cold War ’50s, when many of the best and brightest actors and writers in Hollywood suddenly found themselves blacklisted by the studios and unable to work. Employing three of those formerly blacklisted performers (John Randolph, Jeff Corey, and Will Geer), as part of a cast stuffed with veteran character actors, key television players, a major Hollywood star, and a few favorite Frankenheimer oddballs, Seconds features one of the quirkiest and most compelling ensembles of its era.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.