“I’m made crazy by the way the business structure of movies is now constricting the art of movies,” writes David Denby in a sprawling rant in the New Republic. His argument, which might be read as an update, even a validation of the one Jonathan Rosenbaum laid out 12 years ago in Movie Wars, is that the Hollywood studios have decided to meet the challenge of a rapidly shrinking movie-going public by placing all their eggs in the franchise basket. The big, critic-proof comic book movies they’re rolling out, one after the other, are not only “defoliated of character, wit, psychology, local color,” they’re also radically altering the nature of the art: “At this point the fantastic is chasing human temperament and destiny—what we used to call drama—from the movies. The merely human has been transcended. And if the illusion of physical reality is unstable, the emotional framework of movies has changed, too, and for the worse. In time—a very short time—the fantastic, not the illusion of reality, may become the default mode of cinema.”

Denby grants that “directors such as Martin Scorsese and Steven Soderbergh and David O. Russell and Kathryn Bigelow and Noah Baumbach and David Fincher and Wes Anderson are doing interesting things within the system.” But too many others—he names Paul Thomas Anderson, Bennett Miller, Alexander Payne, Alfonso Cuarón, and Guillermo del Toro as examples—struggle for years between projects to pull financing together. And what are we left with in the meantime? “Constant and incoherent movement; rushed editing strategies; feeble characterization; pastiche and hapless collage—these are the elements of conglomerate aesthetics.” Much of the rest of the piece is a historical account of what’s been lost, namely, in the phrase Denby quotes from André Bazin, “the ripeness of a classical art.”

For Richard Brody, “the underlying engine of David’s lament” is “the desire to see popular filmmaking that wrestles with political history on the wing with the kind of grand-scale audacity shown by Coppola [in Apocalypse Now], or by Chaplin with Modern Times and The Great Dictator. But these filmmakers are precisely the independents, the ones who had their own money in their movies. There is such a thing as historical audacity on a tight budget and an intimate scale—I went into detail about it here a few years ago. But the ultimate question is power—not so much the assimilation of movies to the journalistic and political discourse of the times as the assumption by moviemakers of its position.”

The title of Denby’s TNR piece is “Has Hollywood Murdered the Movies?” And David Thomson‘s in the same issue: “American Movies are Not Dead: They are Dying.” Thomson outlines a history of the idea, which, of course, has been around for decades. But it does seem clear that, for him, the advent of television remains a crucial turning point. Parents would glance at their kids, all “sofa’d up six or seven hours a day,” and say: “‘They’re not really watching. It’s just that the television is on.’ A revolution was hiding in that homily. It condoned inattention—until it became a fashionable disorder; and it accepted that the movie illusion had become climatic more than climactic.”

Hollywood responded to the threat of television by creating experiences that couldn’t be had via small (really small) black-and-white screens. 60 years ago, almost to the day, This Is Cinerama premiered in New York. “And it worked,” reports Susan King in the Los Angeles Times. Cinerama “featured simultaneously projecting images from three synchronized projectors—the movie was shot with three interlocked cameras in a process known as three strip—onto a deeply curved screen. The system, which re-created the full range of human vision, was invented by Fred Waller…. [V]iewers were plunged into the seat of a roller coaster or [travelled] across country on the nose of a B-28 bomber…. Despite the fact it was only in a limited number of theaters, the film was No 1 at the box office. Studios stood up and took notice. Less than a year later, 20th Century Fox presented its first widescreen CinemaScope epic The Robe, and other big-screen formats followed suit including VistaVision, Todd-AO and Super Panavision 70. Cinerama’s legacy can be found today in the popular big-screen format Imax.”

This Is Cinerama is out today in a “Deluxe Combo Blu-ray/DVD Edition” from Flicker Alley, and Dave Kehr reviews the release for the New York Times. At his own site, he notes that the discs “obviously can’t capture the impact the films had on a 70-foot wide curved screen (unless you have a very special video room), but they do summon up the experience with thrilling veracity.”

And Hollywood fights on; no matter what the size of the screen they’re projected on, most blockbusting contenders are now presented in 3D. “Whether you like it or not, 3D is here to stay.” R. Emmet Sweeney interviews Paul W.S. Anderson’s frequent director of photography, Glen MacPherson, “who has shot all three of Anderson’s 3D features: Resident Evil: Afterlife (10), The Three Musketeers (11), and Resident Evil: Retribution. We discussed the technology’s constant evolution, the challenges that places on the production team, and why you can’t easily fake a punch in 3D.”

More reading. In the New York Review of Books, Jana Prikryl reviews the Library of America edition The Age of Movies: Selected Writings of Pauline Kael and Brian Kellow’s Pauline Kael: A Life in the Dark, and she’s got a bone to pick with Kellow. The crux: “Kellow gives a full chapter, almost six pages, to Kael’s ‘broadside’ against Sarris, detailing the arguments made by both critics in their original articles, and says nothing about gender.”

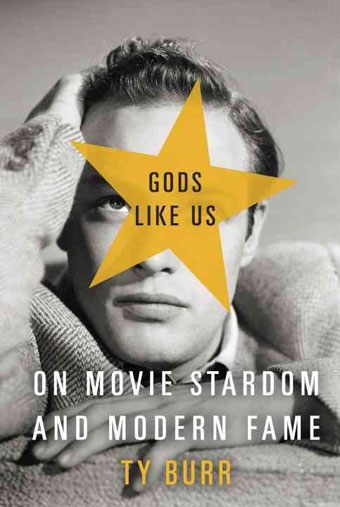

“Any Hollywood history can describe a star’s X factor,” writes Carrie Rickey in the NYT. “But not many film historians can see the whole equation as Ty Burr does in Gods Like Us, his lively and provocative chronicle of the genesis of movie stars and the metamorphosis of movie stardom.” More from Sarah Fenske for the LA Weekly.

David Jenkins, Bill Georgaris, Vadim Rizov, Dan Sallitt, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Dan Callahan have picked up their discussion of the Sight & Sound “Greatest Films of All Time” polls.

That Summer (Un été brûlant, 2011) “marks at last the achievement of a novelistic mode in [Philippe] Garrel’s cinema,” argues Adrian Martin in Transit.

Ted Fendt translates a 1971 interview with Jean Eustache for MUBI’s Notebook, and for the Chiseler, Mitchell Abidor translates a 1941 letter from Louis-Ferdinand Céline to Jean Cocteau.

“Origin and Extinction, Mourning and Melancholia”—Nathan Brown in Mute on Terrence Malick and Lars von Trier.

Recently in the Los Angeles Review of Books: Adam Wilson on Louie, Jonathan Alexander on Treme, Lee Gutkin on James M. Cain, and Mark McGurl on the Gothic tradition in the 21st century.

In other news. On Thursday at 7:30 pm in London (1:30 pm in New York, 10:30 am in LA), The Space will host the exclusive, one-time-only online premiere of the new restoration of Alfred Hitchcock’s silent comedy Champagne (1928). For the BFI, curator Bryony Dixon describes the challenges the film presented its restorers; and the Guardian presents a clip.

Megan Griffiths is the winner of the Stranger‘s 2012 Genius Award for Film; Charles Mudede explains why “Griffiths’s win wasn’t a big surprise. The film that secured her nomination, Eden, is, after all, a masterpiece.”

New York. Michael Almereyda’s Another Girl, Another Planet, tonight at Light Industry.

In the works. “In his foray into American television, Oscar-nominated filmmaker Alfonso Cuarón has teamed with J.J. Abrams for a high-concept drama, which just landed at NBC with a pilot production commitment,” reports Deadline‘s Nellie Andreeva. Also: “FX has closed a deal to develop Fargo, an hourlong project loosely based on the Coen brothers’ 1996 comedic crime drama.”

Listening (18’39”). For the New Yorker, Margaret Talbot talks with Richard Brody and Michael Agger about her father, Lyle Talbot, “who appeared in hundreds of films opposite the likes of Ginger Rogers and Carole Lombard.”

More browsing? See the Film Doctor and Girish Shambu (I’m particular wowed by This Long Century).

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.