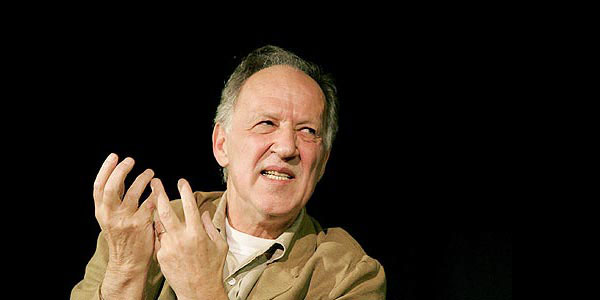

Werner Herzog, all summer long. The BFI’s Herzog season opened this weekend and will run through the end of July; then, in August, the Festival del film Locarno will accompany its presentation an honorary Leopard to the German-American director with a ten-film retrospective.

In the Guardian, Michael Newton notes that “Herzog’s image is very present on the internet,” and he lists a good number of clips from films and interviews, parodies and mashups that’ve gone viral over the years. But the piece may have been turned in too early to catch the new favorite, Robin Frohardt‘s Fitzcardboardaldo:

Just as enchanting—and funny—is the making-of, The Corrugation of Dreams, the title being, of course, a play on Les Blank’s remarkable documentary on the making of Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo (1982), Burden of Dreams (also 1982). The short is even built on audio from Burden, a clip from probably the greatest improvised monologue in cinema:

Newton:

In overview, his movies can look like a series of Graham Greene novels rewritten by D.H. Lawrence. Just as Greene had Greeneland, Herzog has Herzogland, and the two realms, at the very least, share a border. Like Greene, Herzog would presumably assert that the place of his films is no invented country, but simply the world as in fact it is. The variety of locales and milieux in his films is astonishing: from the Peruvian jungle in the stunning Aguirre, Wrath of God (1972) to the Biedermeier Germany of Nosferatu and Woyzeck (both from 1979); from the dusty pre-tourist Lanzarote of Even Dwarfs Started Small (1969) to the science-fiction landscapes of the Kuwaiti oil fires after the first Iraq war in Lessons of Darkness (1992). The richness of his interests is amazing: ecstatically devout pilgrims; prehistoric cave paintings; fast-talking American auctioneers; ski‑jumpers; TV evangelists; Siberian trappers; the blind, deaf and dumb. He has made more than 60 films, both fiction and documentaries, and, in total, they look like the life’s work of several directors, yet all maintain the spirit of one man’s view of this disparate planet.

Speaking of Aguirre, here’s the BFI’s trailer for the new restoration:

Tim Robey in the Telegraph: “Tracing the steps of the ruthless Spanish conquistador Lope de Aguirre, who dragged an exhausted band of followers down the Amazon and Orinoco rivers in search of El Dorado, it’s a grand statement on folly and the impotence of the human ego—Shelley’s ‘Ozymandias‘ in film form. Perhaps realizing that the best way to portray a demented egomaniac was simply to cast one, Herzog persuaded his countryman Klaus Kinski to take the role, in the first of five films they would make together. It is perhaps the stormiest, most bitterly violent actor-director partnership in the history of cinema, and among the most creatively fruitful.”

Back in the Guardian, Ben Child notes that “Herzog has delivered a public-safety advertisement in the US about the dangers of texting and driving.” Here’s the PSA for AT&T:

And the last word for now goes to Tim Robey:

re: Herzog’s animals, I did mention the incredible dancing chicken at the end of STROSZEK, but it was cut for space.

— Tim Robey (@trim_obey) June 2, 2013

Update, 6/4: David Jenkins writes up a Herzog top ten at Little White Lies.

Updates, 6/9: Graham Fuller at the Arts Desk: “Wagnerian in scale and neo-colonialist in its perilous production, as was Fitzcarraldo, Herzog’s other Peruvian folie de grandeur, Aguirre is the most damning depiction of colonization in a career that has repeatedly condemned the destruction of what he has called ‘the embarrassed landscapes of our world.’ Simultaneously, it is the masterpiece of the New German Cinema most infused with the spirit of 19th-century Romanticism. Although Wim Wenders also drew on the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich in Wrong Movement, Aguirre more faithfully replicates Friedrich’s vision of nature aweing human onlookers, or engulfing man’s feeble structures. In returning to the past, Herzog was attempting to efface the stain on German art and cinema left by the Nazis.”

More on Aguirre from John Bleasdale (Electric Sheep), Peter Bradshaw (Guardian, 5/5), Cath Clarke (Time Out, 5/5), Philip French (Observer), David Jenkins (Little White Lies), and Anthony Quinn (Independent, 5/5).

Update, 7/4: From Tim Robey in the Telegraph: “One seam of Werner Herzog’s formidable career has always been his interest in congenital misfits–those removed, especially by language, from living inside the norms of society. The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, his 1974 drama about a Nuremberg foundling, is the peak of these achievements, and one of his two or three finest films, not to mention surely his most humane.”

Updates, 7/5: The Guardian‘s Peter Bradshaw notes that Kaspar Hauser, “an unmissable film,” is “based on the true story of a 16-year-old youth who appeared out of nowhere in a German square in 1828 like an unwanted pet; having apparently been imprisoned and beaten as a child, he is all but savage, but nonetheless is taught to speak and reason by kindly townsfolk and briefly taken up by fashionable society.”

BFI programmer Geoff Andrew: “Herzog isn’t, in fact, very concerned with the ‘enigma’ of Hauser’s origins, identity or fate; for him those are incidental to what Hauser’s predicament—his position as an ‘innocent’ thrust into the social and ethical straitjacket we like to call ‘civilization’—enables him to say about what he sees as the human condition…. Kaspar could not be more ‘particularized’—instead of a professional actor, Herzog chose Bruno S, himself a social outcast whose behavior and manner of speaking firmly rooted the character he was playing in a very tangible ‘reality.’ Moreover, the story favors moments of intimate interaction over scenes with overt ‘big’ statements. Working outwards from the individual to the wider world, Herzog privileges Kaspar’s point of view—even his dreams—so that we may share his bemusement at what he encounters in his new life. It’s a strategy the writer-director has often adopted over the years, even to the extent of imagining, in works like Fata Morgana (1971), Lessons of Darkness (1992) and The Wild Blue Yonder (2005), how aliens might regard humanity’s ambitions and achievements.”

Update, 7/6: “If The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser were a Bob Dylan album, it would be called ‘Another Side of Werner Herzog,'” suggests David Jenkins at Little White Lies. “Where Aguirre, the Wrath of God offered one man in tempestuous dialogue with the divine, here the register is placid, serene and at times extremely melancholy.”

Update, 7/21: Werner Herzog: Parables of Folly and Madness, a series of early work, will screen at the Film Society of Lincoln Center in August.

Updates, 8/16: At Twitch, Dustin Chang previews the FSLC series, opening today and running through August 22, by focusing on Signs of Life (1968), Even Dwarfs Started Small (1970), and Heart of Glass (1976).

In Locarno, Alexandra Zawia‘s interviewed Herzog for the Hollywood Reporter.

Update, 8/17:

Clips from the masterclass in Locarno

Update, 8/18: Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn prefaces his notes on the masterclass by noting that Herzog met Abel Ferrara in Locarno and the two discussed the Bad Lieutenant brouhaha. Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2009) was sold as a remake of Ferrara’s 1992 original, and neither director was really comfortable with that notion, to put it mildly. But their chat seems to have gone well.

Update, 8/19: Herzog’s installation Hearsay of the Soul is on view at the Getty through January 19, and for Special Affects, Jordan Schonig argues that it “should be given our sincere attention, less as a celebrated artistic debut than as a window into the mind of an enigmatic filmmaker.”

Update, 8/21: “Shout! Factory and Werner Herzog Film have signed an exclusive multi-platform distribution partnership involving 16 remastered titles from the Herzog library,” reports Jeremy Kay for Screen Daily.

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.