“Gore Vidal, the elegant, acerbic all-around man of letters who presided with a certain relish over what he declared to be the end of American civilization, died on Tuesday at his home in the Hollywood Hills section of Los Angeles, where he moved in 2003, after years of living in Ravello, Italy.” Charles McGrath in the New York Times: “Mr. Vidal was, at the end of his life, an Augustan figure who believed himself to be the last of a breed, and he was probably right. Few American writers have been more versatile or gotten more mileage from their talent. He published some 25 novels, two memoirs and several volumes of stylish, magisterial essays. He also wrote plays, television dramas and screenplays. For a while he was even a contract writer at MGM. And he could always be counted on for a spur-of-the-moment aphorism, putdown or sharply worded critique of American foreign policy.”

In the Los Angeles Times, Elaine Woo writes that Vidal, who was 86, “also brought shrewd intelligence to writing Broadway hits, Hollywood screenplays, television dramas and a trio of mysteries still in print after 50 years. When he wasn’t writing, he was popping up in movies, playing himself in Fellini‘s Roma, a sinister plotter in sci-fi thriller Gattaca and a U.S. senator in Bob Roberts…. Vidal also turned his talents to screenplays, which included his successful adaptation of Tennessee Williams’s Suddenly, Last Summer. He was an uncredited writer on the 1959 blockbuster Ben Hur, contributing what he described as a homoerotic subtext to the relationship between the two male leads, Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd. (His last major screenwriting credit was for the X-rated Caligula, a disastrous 1979 film produced and co-directed by Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione.) In 1960, the same year that The Best Man opened on Broadway, Vidal made his political debut, running for a House seat as a liberal Democrat in a conservative upstate New York district…. Vidal was far more successful writing about political power than acquiring it.”

Two writers for the Nation, where Vidal was a contributing editor and published over 40 articles, look back on their colleague. John Nichols: “Gore Vidal loved America in the way that the best of the founders did. Indeed, he seemed at times, to be the last of their number—a fierce defender of the purest, most revolutionary of ideals at a time when the contemporary political class prattled on about Constitutional principles they neither understood nor valued. (At the bicentennial, in 1976, Time magazine featured a cover with Vidal in historic garb; an honor that delighted him sufficiently to earn a place for the cover on the wall of his Italian villa.)”

And Jon Weiner: “One of Gore’s memorable quotes had special meaning for me—it came in his unexpected appearance in the 2006 documentary The U.S. vs. John Lennon, based on a book I wrote about Nixon’s attempt to deport Lennon in 1972 because of his anti-war activism. ‘Lennon was a born enemy of those who govern the United States,’ Gore said with a twinkle in his eye. ‘He was everything they hated…. he represented life, and is admirable; and Mr. Nixon and Mr. Bush represent death, and that is a bad thing.'”

Viewing. “During the 1960s and 70s, Vidal feuded publicly with literary and political foes alike. Sometimes it made for good TV. Other times it made for bad TV. It didn’t really matter. He was ready to go.” At Open Culture, Dan Colman posts clips of Vidal going after Norman Mailer and William F. Buckley.

Updates: “Vidal liked to present himself as an insider—a man who understood the world and how it worked,” writes Jay Parini. “This knowing quality, registered in the tone of his prose, permeates the essays. Their edge and vitality derive from his complete mastery of the scene he described, whether ridiculing Ronald Reagan as ‘a triumph of the embalmer’s art,’ reassessing the presidency of John F Kennedy, outlining the theory of the French ‘new novel’ or reconsidering the importance of Montaigne or Somerset Maugham…. Always intent on living well, Vidal needed a good deal more money than his fiction attracted. Not surprisingly, he turned to television, Hollywood and Broadway to expand his income. ‘I am not at heart a playwright,’ he explained at the time, with typical candor. ‘I am a novelist turned temporary adventurer; and I chose to write television, movies, and plays for much the same reason that Henry Morgan selected the Spanish Main for his peculiar—and not dissimilar—sphere of operations.'”

Also in the Guardian, Xan Brooks collects clips from films Vidal either wrote, co-wrote or appeared in.

“Farewell the classic films, hail the television commercial!” Glenn Kenny posts a passage from Myra Breckinridge.

Granta republishes Vidal’s story from its 32nd issue, “An Epistle to a New Age.”

The BBC collects some of Vidal’s best quips.

Vidal in the New York Review of Books; e.g. (via Movie City News), “Remembering Orson Welles” from 1989.

Listening. The Leonard Lopate Show posts interviews from 2006 and 2009.

In the Guardian, John Francis Lane looks back on Vidal’s time in Rome: “Ben-Hur was one of several movie mishaps for Gore in Hollywood-on-the-Tiber.”

The 1974 Paris Review interview.

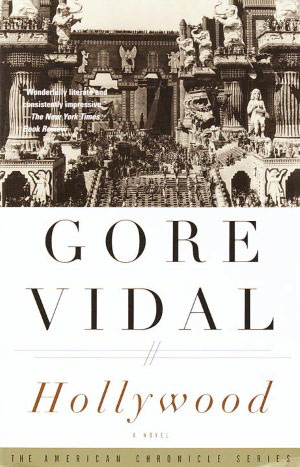

David L. Ulin in the LAT: “His 1948 novel, The City and the Pillar, was an early examination of homosexuality; his 1968 novel, Myra Breckinridge, revolved around a transsexual. But it was really with the publication of Burr in 1973 that he embarked upon what is his lasting literary achievement: a seven-novel series called Narratives of Empire, which traces both the promise and the failure of the American experiment from the Louisiana Purchase to the Cold War…. For Vidal, contemporary America could be best interpreted as a reflection of ancient Rome: a republic that had become an empire and, in so doing, had fallen prey to empire’s corruptions, empire’s woes. This is the story to which he returned, in both his writing and his public appearances, and it illustrates a fundamental tension that he never quite resolved. Vidal, after all, was both insider and outsider: an aristocrat who saw the failings of the aristocracy, a true believer whose belief had been betrayed.”

David Ehrenstein comments on the first round of obits, posts a few clips, adds some rare photos and spices it all up with a few recollections of his own.

Time‘s Richard Corliss suggests that Vidal “may be best remembered for The Best Man, produced in 1960 and revived in many election years (including this one). This pièce-à-clef imagined the Presidential primary faceoff between an Adlai Stevenson type, ethical but dithering, and a venal Richard Nixon surrogate. The winner of the real election in 1960 was John F. Kennedy, whose wife was Vidal’s kin by marriage and whose presidency was a frequent butt of Vidal’s essayist venom. This man of letters always wielded a poison pen.”

“[C]ould he have written the novels (or even come up with all those one-liners), if he had never signed a Hollywood contract?” asks Jonathan Myerson in the Guardian.

“By embracing public visibility and the cultural conversation, by extending his presence through runs for political office and so many realms of work, Vidal was able to expand his reach far beyond what the typical 20th-century writer achieved,” argues Zachary Wigon in Filmmaker.

Jon Michaud presents a guide to Vidal’s pieces in the New Yorker.

Esquire posts the long 1990 interview with Vidal and Norman Mailer in which they get along pretty damn well, thanks.

Updates, 8/2: “Broadway theaters are to dim their lights on 3 August in memory of Gore Vidal,” reports the Guardian, “and the cast of his play The Best Man, currently on at the Gerald Schoenfeld Theatre, will dedicate the next week of performances to his memory.”

Vidal in the TLS.

NYT Book Review editor Sam Tanenhaus rewatches the Vidal-Buckley Jr. face-off and notes that “what is most striking to the contemporary viewer is how much the combatants resemble each other, beginning with their languidly patrician tones. The phrases come from the gutter, but plainly Mr. Vidal and Buckley do not. They exude the princely confidence once associated with well-born Americans of a certain pedigree…. Buckley and Mr. Vidal both subscribed, though in very different ways, to the ideal of American exceptionalism—with its suggestion that even as the nation stood apart from or above other nations, it was susceptible to foreign infection. Mr. Vidal feared the evils of empire building (a continuous theme in his historical novels) and warned against the decline that had overtaken other civilizations brought low by imperial hubris. For Buckley the threat came from global communism and ‘statist’ domestic policies that would reduce Americans to servitude and weaken their connection to the moral values of Christianity. It was this two-sides-of-the-same-coin idealism that led to the heated exchange in 1968.”

Christopher Buckley comments on the feud between Vidal and his father for the New Republic: “The evidence suggests Vidal never deserted his demons and took them with him to the grave.”

“I got a lot of stimulating jolts of mental and political adrenaline out of Gore Vidal’s polemical essays over the years,” blogs the New Yorker‘s Hendrik Hertzberg. “But what I’ll always be grateful to him for is the sheer pleasure—the voluptuous, luxurious, forget-everything-for-now-except-this-paperback-I’m-clutching oblivion—that was the gift of his historical fiction.”

In the Los Angeles Review of Books, F.X. Feeney has a must-read piece on Vidal’s career as a screenwriter, its influence on his novels and more. “In his 1976 essay: Who Makes the Movies? Vidal asserted that, ‘For all practical purposes, the screenwriter continues to be the primary creator of talking film.’ Apart from such exceptions as Hitchcock, Welles and Bergman, a typical film director is at worst a brother in law and at best a technician, a ‘hustler-plagiarist who has for twenty years dominated and exploited and (occasionally) enhanced an art form still in search of its true authors.’ After quoting a passage from Vidal’s screenplay for Michael Cimino’s The Sicilian (1987), Feeney asks, “Pure Vidal? Is that possible in a collaborative medium? Yes. His ear for dialogue is natural, precise, and so idiosyncratic–note the rhythms and repetitions–that with little study you can pick his contribution out of a crowd of collaborators. Which brings us to Ben-Hur….”

Updates, 8/3: Vidal “is not someone who deserves to be spared the rigors of a reckoning,” argues David Greenberg in Slate. “Toward the end of Vidal’s life, he discredited himself even on the left with his embrace of loony ultra-right causes, such as Ruby Ridge, Waco, and eventually Timothy McVeigh, who blew up the Oklahoma City Murrah building in 1995…. The Sage of Ravello was an equal-opportunity apologist for terrorists, taking up the obscene theories (which, in an exquisite Orwellism, go by the name ‘truther’) that the Bush administration was complicit in al-Qaida’s 2001 attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon…. Vidal’s extreme late-in-life beliefs, however, weren’t deviations from an otherwise noble record. They were the natural progression of thought in a man whose worldview was fundamentally racist and elitist, motivated by the fear that the reign of his own caste was ending as the walls of aristocratic privilege crumbled in the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust.”

“His work was about asking why society could not deal with its own essential failure, and how did it become his problem anyway?” Hilton Als for the New Yorker: “I think his continual battle with writers like Norman Mailer, Capote, and probably James Baldwin, had to do with the fact that they did the legwork Vidal never really did do. I think he would have made a fabulous reporter, bringing his discerning eye to the world’s foibles. Instead, we must settle for the fabulous memoirist who couldn’t help loving artists like Dawn Powell, [Tennessee] Williams, Henry James, and so on, even as he stood on the other side of their deep and fearless ability to feel, and to make mistakes, as only the true artist can.”

From the Nation: “Here are some of his more powerful essays from nearly half a century of writing for this magazine.”

Update, 8/5: chained and perfumed excerpts Vidal’s furious attack on Myra Breckinridge director Mike Sarne—and Sarne’s “near-incomprehensible” rebuttal.

Update, 8/6: “The most cunning, odious and successful of Gore Vidal’s provocations was surely a mid-career contribution to a special issue of The Nation in 1986,” writes Paul Berman in the New Republic. “His argument was a Ku Klux Klan screed…. Still, it has to be acknowledged that Vidal’s Nation tirades established a vein of modern political writing, which you could follow in later years through the columns of still other Nation writers, the late Alexander Cockburn and the late Christopher Hitchens (during the period before Hitchens admirably threw off the combined Vidal-and-Cockburn influence), with their habit of puzzling the left-wing masses in one publication or another by praising the virtues of the American militia movement or Marine Le Pen or the philo-Nazi historian David Irving. This was the world of red-brown hipsterdom, which, now that Vidal, too, has passed from the scene, appears to have been eclipsed for the moment in its English-letters version. But it survives and even flourishes in the turgid continental-philosophy version of Slavoj Zizek and Alain Badiou, and therefore will be flourishing for years to come in the American universities.”

Update, 8/10: “I think it took me all of one day to read Myra Breckinridge in full and possibly a month to process it,” writes Henry Giardina for the Paris Review. “The cartoon version of gender deviance it put forth was one that, against all odds, enraptured me…. Vidal’s Myra, the militant transgender feminist, was dangerously close to my own idea of an ideal queer: a person so aggressively gay as to be a kind of enemy of the state.”

Update, 8/17: “Screening History originated as one of the William E. Massey, Sr. Lectures on the History of American Civilization that are delivered every two years at Harvard by a notable personage,” writes Nick Pinkerton for Sundance NOW. “‘As I now move, graciously, I hope, toward the door marked Exit,’ the address begins, ‘it occurs to me that the only thing I ever really liked to do was go to the movies.’ Screening History sets down in prose, for the first time, biographical details that would be fruitfully expanded in Vidal’s memoir Palimpsest. It consists of three parts, the first of which is a recollection of Vidal’s early infatuation with the movies as viewed from Washington D.C.’s picturehouses. The second, ‘Fire Over England,’ is an analysis of the Anglophiliac Hollywood of the ‘30s, which old isolationist Vidal interprets as a P.R. barrage by Brit émigrés and UK propagandists—including Alexander Korda and script punch-up man Winston Churchill—for the purposes of whipping up American sympathies for the cause of ‘gallant-little-England.'”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.