Centennial tributes to Gene Kelly have been popping up around the country since at least May, when the Academy hosted two special evenings and Susan King wrote in the Los Angeles Times that “he was the complete package, an innovative actor, dancer, choreographer and director. But let’s not forget another obvious fact—few dancers have looked as sexy on the silver screen. While lean, dapper Fred Astaire, who came into films almost a decade before Kelly in 1933, often danced dressed in a top hat, white tie and tails, the athletic Kelly preferred tight, form-fitting pants and shirts. No wonder it was said that the difference between Astaire and Kelly is that Astaire was the person you went to the dance with and Kelly was the one you went home with.”

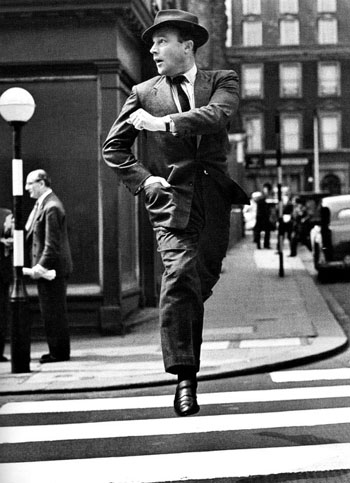

When New York’s Film Society of Lincoln Center ran its two-week retrospective last month, Melissa Anderson, writing for the Voice, picked out a quote from The Memory of All That, the 2003 memoir by Betsy Blair, Kelly’s wife from 1941 to 1957: “A sailor suit or his white socks and loafers, or the T-shirts on his muscular torso, gave everyone the feeling that he was a regular guy, and perhaps they too could express love and joy by dancing in the street or stomping through puddles…. He democratized the dance in movies.”

And Dan Callahan wrote for Alt Screen: “Being a guy to him meant being down to earth, literally. Dancing with the Nicholas Brothers in The Pirate (1948), Kelly gets down with them and does a Russian kazaki dance and then glides across the floor on his calves, just like Irish dancer and showman George M. Cohan used to. ‘I have a lot of Cohan in me,’ Kelly once told an interviewer. ‘It’s an Irish quality, a jaw-jutting, up-on-the-toes cockiness—which is a good quality for a male dancer to have,’ he insisted, always scorning anything in dance that could possibly be construed as effeminate. He loved to pinwheel his arms round and round as if he was a man-made machine, not so much an airplane but a plow or a tractor or a watermill.”

Kelly was a “fluid icon,” writes Daniel Guzmán at Cinespect, “moving from room to room, from category to category, graceful on any stage, be it in film, television, or beyond. His legacy is everywhere now, on shows such as Glee and So You Think You Can Dance? and in multifaceted performers such as Justin Timberlake and Beyoncé Knowles.”

NPR’s Susan Stamberg talks with New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce: “So entertaining. So exuberant. So excited and happy to be there. I think he’s basically a comic, and a comic dancer.” But also: “Kelly to me is a very weighty dancer. He really gets into the floor, and his body develops his rhythm in connection with actual tap dancing.”

All of which brings us to the celebration going on right now at Not Coming to a Theater Near You. Introducing the week-long feature, which so far has included Victoria Large on For Me and My Gal (1942) and On the Town (1949) [update, 8/24: and Summer Stock [1950]), Cullen Gallagher on Christmas Holiday (1944), and Veronika Ferdman on The Pirate, Victoria Large writes: “His characters have the potential to hurt and be hurt, and they frequently mask their insecurities with a bravado that threatens to slip. Yet this humanity and indeed, vulnerability, in many ways places Kelly’s grace and confidence as a dancer in sharper relief. Those perfect little moments in Kelly’s dance routines—think of his effortless leap onto the lamppost in Singin’ in the Rain [1952], or that expertly executed knee-slide during the ballet sequence in On the Town—are transcendent in part because we know that his characters have something to transcend.”

Listening. Slate‘s Stephen Metcalf, Dana Stevens, and Julia Turner discuss Singin’ in the Rain on the film’s 60th anniversary—and Kelly’s brilliance in general.

Updates: “From Broadway to music videos, R&B concerts to the big screen, choreographers of all stripes still draw on the work of Gene Kelly.” Blogging for Slate, Aisha Harris lays out several examples.

“The two films which secured his reputation—An American in Paris [1951], and Singin’ in the Rain—two of the great screen musicals—followed close on the heels of each other in 1951 and 1952,” notes Sarah Crompton in the Telegraph. “At the time it was Minnelli’s An American in Paris, with its extraordinary 17 minute dream ballet sequence, a vivid tour de force created by Kelly and starring him and Leslie Caron, that won most acclaim. Singin’ in the Rain, on which Kelly was once again co-director, was oddly less enthusiastically received. Now, of course, it regularly tops polls as the best film musical ever.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.