“Long-term Japan resident, writer and critic Donald Richie, who through dozens of books and articles published from the late 1940s until the last decade helped introduce Japanese film and culture to the world, passed away in Tokyo on Tuesday,” reports Edan Corkill in the Japan Times. Richie was 88.

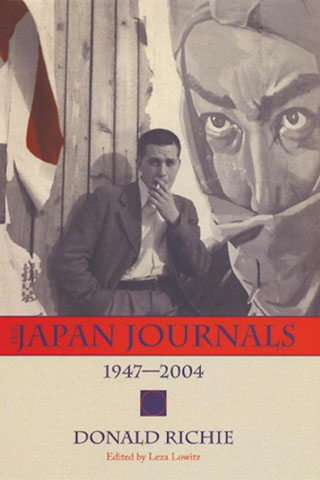

“Japan has never attracted the attention of a Chatwin or a Naipaul, let alone fostered a Kipling, a Somerset Maugham, a Hemingway or a Paul Bowles,” wrote Richard Lloyd Parry in 2006, reviewing Richie’s The Japan Journals: 1947-2004 for the London Review of Books. “No one has had a greater yearning or been better qualified to fill this gap than Donald Richie. ‘Almost everything I do, everything that is known about me, is connected to this country,’ he wrote. ‘To be a person so intent upon describing a place not his own—isn’t this odd?’ Over sixty years in Japan, he has been a reporter, tour guide, cinema critic, film director, print-maker, novelist, travel writer, editor, teacher, subtitler, public speaker and actor. Apart from fiction, both short and long, and countless newspaper columns and reviews, he has published books about film, art, Zen, history, tattoos, gardens, temples, phallic symbols, food and bonsai. He has been a friend to famous and talented foreigners and to a cross-section of the most interesting Japanese of the second half of the 20th century.”

Introducing what turned out to be a terrific interview in 2003, Jasper Sharp also mentioned Richie’s literary oeuvre, but then added that, naturally, “he is best known to Midnight Eye readers for his groundbreaking works on Japanese cinema, including books on Kurosawa and Ozu, the first ever in-depth look at Japanese cinema in The Japanese Film: Art And Industry, co-written with Joseph L. Anderson, and his more recent reappraisal, A Hundred Years of Japanese Film. He was also active in the experimental filmmaking scene of the 1950s and 60s.”

Pete Larson recalls sitting in on Richie’s class on Japanese cinema at the University of Michigan in the early 90’s: “It was too late to add the course to my schedule, but I went anyway, listened to the first lecture and was immediately hooked…. I think I learned more about art, cinema, media, culture, social science, the humanities and politics in that one seven-week course that I did in the entire remainder of my undergraduate education.” And he’s posted one of Richie’s films, Boy with Cat (1966).

In 2006, as part of the Museum of the Moving Image’s Pinewood Dialogues, Richie “discussed his career with Assistant Curator Livia Bloom, following a program of his own experimental short films: Life, Atami Blues, Dead Youth, and Five Filosophical Fables.” The audio runs 34’37”.

“Donald Richie began writing regularly for the Japan Times in 1954, initially writing film and stage reviews. In the early ’70s he began writing book reviews and continued contributing until 2009.” The paper presents an archive.

Catherine Grant presents a collection of links to scholarly work on Japanese cinema that leads with a video interview with Richie. And she’s added a new entry at Film Studies for Free dedicated specifically to Richie and his work.

Harry Kreisler interviewed Richie in 2001 as part of the Berkeley series Conversations with History.

Updates: In this clip from The Story of Film: An Odyssey, Richie, Mark Cousins, and Kyōko Kagawa discuss Ozu’s life and films:

And Criticwire‘s Matt Singer‘s posted clips of Richie introducing Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) and Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962).

Criterion’s Kim Hendrickson met Richie “when he came to New York to record a commentary track for our DVD edition of Rashomon. It was the beginning of our friendship and of many collaborations…. I visited Donald this past December in Tokyo, to say hello and, knowing he was declining, to say good-bye. He greeted me as he always did, with that incomparable smile and a slight twinkle in his eye. Donald taught me much about Japanese cinema, but that pales in comparison with what I learned from him in other ways.”

Ryan Gallagher‘s put together a list of Criterion releases featuring Richie’s commentaries and supplements, and heavens, there are many.

Update, 2/20: Richie “won recognition for his soul-baring descriptions of a Westerner’s life in an impenetrable but permissive society that held him politely at arm’s length while allowing him to explore it nonetheless, from its classical arts to its seedy demimonde,” writes Martin Fackler in the New York Times. “‘I may have rejected the U.S.A. where I was born,’ Mr. Richie wrote in his memoir, ‘but I did not decide to be Japanese. That is an impossible decision, since the Japanese prevent it. Rather, I decided to decorate Limbo and become a citizen of this most attractive, intensely democratic republic.'”

Update, 2/21: “Though recognized as the most important figure in introducing Japanese cinema to the west, Richie saw himself as a writer foremost and a film critic secondarily,” notes Jasper Sharp in the Guardian. “His fictional work includes Memoirs of the Warrior Kumagai: A Historical Novel (1999), A View from the Chuo Line and Other Stories (2004) and Tokyo Nights (2005). His interests stretched to topics as diverse as the country’s literature (Japanese Literature Reviewed, 2003), modern fashion (The Image Factory, 2003) and travel. Twenty years after its publication, his personal travelogue The Inland Sea (1971) was turned into an award-winning documentary by Lucille Carra and Brian Cotnoir. Richie narrated the film himself…. [H]e always remained strongly aware of his intermediary status, as he explained when I interviewed him in 2003 for the website Midnight Eye: ‘My interest in Japan is—in a literal sense of course, but in sort of a metaphorical sense—that I’m using the idea of the outsider, the foreigner, as my own vehicle as well. He flourishes here because he knows he can’t join.'”

Update, 2/23: “For the past half century, Donald’s name has been almost a synonym for Japanese cinema,” writes Peter Cowie at Criterion’s Current. “His numerous books not only made him the guiding light on the subject but also exemplified a kind of fluent prose that eludes the zillions of bloggers in today’s movie criticism world. He wrote without affectation, engaging his reader in a cool analytical discourse. The clarity of his thought, if not the waspishness of some of his judgments, stemmed from a profound self-confidence that sometimes failed him in private life. Donald was indeed an intellectual, but an intellectual for whom film theory, and terms like semiotics and structuralism, were anathema. His fuel was enthusiasm—a simmering passion for life as expressed through literature (by authors as diverse as Lafcadio Hearn, Nagai Kafu, and Henry Green), through film, through Japanese theater, and above all, through the human personality, which he observed so keenly.”

Updates, 2/26: “By talking about Japanese cinema in terms amenable to Western tastes, he integrated it into our film culture,” writes David Bordwell. “Kurosawa as a robust humanist; Ozu as the serene contemplator of life’s transience: these became familiar figures thanks to his eloquent critical rhetoric. At the same time he retained a sense of their uniqueness, insisting in particular on the irreducible Japaneseness of Ozu’s aesthetic…. Some readers expect the Journals to be among the author’s most lasting work. They’re valuable as chronicles of the daily life he observed with sympathetic but dispassionate acuity, but they also record the mind and feelings of a man of Wildean sensitivity wandering among dazzling surfaces that kept his senses, and his libido, ever on the alert.” It’s a beautiful remembrance, followed by links to more reading and a tribute page.

Kyoko Hirano, former Director of Japan Society’s Film Center and a longtime friend: “He not only introduced the giants of Japanese classic film to the rest of the world—Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Naruse, Kinoshita, Gosho, Hani, Oshima, Shinoda and so on—but was always interested in upcoming young talents like Hayashi, Sakamoto, Kore-eda and Shinozaki, and promoted them tirelessly…. He enchanted people, young and old, and his extraordinary humanity created devoted fans all over the world.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.