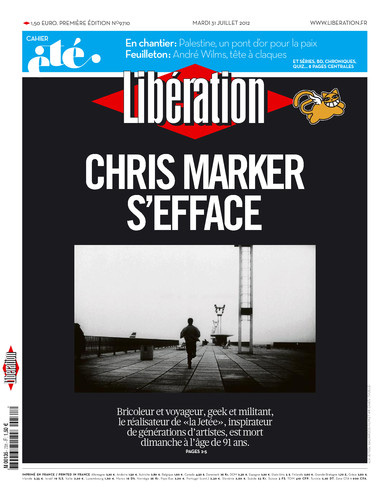

“Chris Marker, born Christian-Francois Bouche-Villeneuve, July 29, 1921 in Neuilly-sur-Seine (Hauts de Seine) died on Monday at the age of 91,” reports Libération. The news was broken via Twitter this morning by French critic Jean-Michel Frodon and Cannes Film Festival president Gilles Jacob.

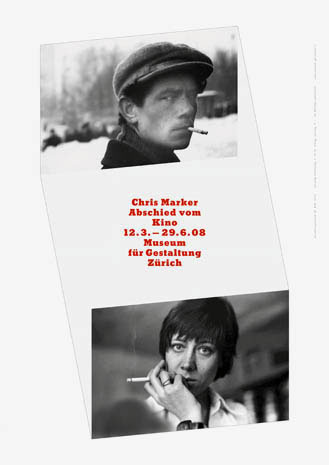

“La Jetée (1963) and Sans Soleil (1983), made a tidy twenty years apart, are the twin peaks of Chris Marker’s creative achievements and his best-loved and most widely seen films,” wrote Catherine Lupton, author of Chris Marker: Memories of the Future, for Criterion in 2007. “But who is Chris Marker? Writer, photographer, editor, filmmaker, videographer, and digital multimedia artist, Marker was until recently one of cinema’s better-kept secrets, famously reclusive and shrouded in protective layers of legend and pseudonym. The whisper of his adopted name was for those in the know a password to another country: an alter ego of the everyday modern world, transfigured by the insight of a wise, funny, and profoundly humane intelligence, populated with owls, cats, and mysteriously beautiful women, a place where, as we learn in Sans Soleil, ‘every memory can create its own legend.'”

“Arguably the cinema’s greatest essayist, he transcends traditional documentary with his exhilaratingly personal reports on the world, discursive filmed letters which—even in Le Joli Mai, a comparatively straightforward cinéma verité account of Parisians in 1962—adopt the quizzical perspective of a stranger in a strange land.” Geoff Andrew in The Director’s Vision (1999), as quoted at They Shoot Pictures, Don’t They?.

Jaime N. Christley for Senses of Cinema in 2002:

While one normally pictures such Cahiers du Cinéma graduates as Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer when discussing the French cinema of the late 50s and early-to-mid 60s, there also existed the Left Bank directors, who, according to Richard Roud, included three people: Agnès Varda, Alain Resnais, and Marker. Any division between the New Wave and the Left Bank cinemas became increasingly problematic as the 60s progressed, and as the French intelligentsia became more and more politicized. All of the things that were critical in the early part of the New Wave/Left Bank periods: cinéma vérité, jump cuts, the fixation on American film noir, the neighborhood (Champs-Elysées, Cahiers, Paris, Europe)-centric attitudes, were discarded or modified accordingly to suit an increasingly global, and increasingly anxious, worldview. A multi-episodic collaboration between Marker, Godard, Varda, Resnais, William Klein, Claude Lelouch, and Joris Ivens, Loin du Vietnam (1967), created as a means to express sympathy with the North Vietnamese, was both an explicit embodiment of this “new” consciousness, as well as—perhaps not coincidentally, as Roud suggests (Roud, 668)—a movie made during a period when Marker decided to make films in collaboration with one or more other directors, rather than on his own: others included À bientôt, j’espère (co-directed by Mario Marret, 1968) and La Sixième face du pentagone (co-directed by François Reichenbach, 1968). This was also the period in which Marker founded the SLON (Societe pour le Lancement des Oeuvres Nouvelles) production studio, an on-again, off-again (when overcome by events) filmmaking collective devoted to making socially and politically conscious works. Marker was also involved with Godard and Resnais in making and distributing “cinétracts,” 16mm promotional pieces intended as “news bulletins” for and about students and workers during and around the May 1968 revolt. Marker would later make (and even later, modify) Le Fond de l’air est rouge (1977-1993), also known as A Grin Without a Cat, as a way to reflect upon the rise and fall of the left during the 60s and 70s.

Just yesterday, This Must Be the Place, one of the finest tumblrs dedicated to cinema, celebrated Marker’s birthday with a quote from Alain Resnais: “Chris Marker is the prototype of the 19th Century man. He managed to achieve a synthesis of all appetites and obligations without ever sacrificing any of them to the others. In fact a theory is making the rounds, and not without some grounds, that Marker could be an extra-terrestrial. He looks like a human, but perhaps he comes from the future or from another planet… There are some very bizarre clues. He is never sick or ill, he is not sensitive to cold, and he doesn’t seem to need any sleep.”

We’ll be gathering remembrances in the days and weeks to come, but for now, let me refer you to the excellent resource Chris Marker: Notes from the Era of Imperfect Memory, a 2010 issue of Image [&] Narrative devoted to Marker, and acquarello‘s reviews.

Updates: “Chris Marker is in town.” Laurent Kretzschmar has posted an excerpt from Serge Daney‘s notes from the Hong Kong originally published in Cahiers in 1981.

“[I]s there any ‘filmmaker’ who faces the shifts within his chosen medium with such blissful unconcern as Chris Marker?” asked Andrew Tracy in Reverse Shot in 2008. “Marker’s swearing off of film for good in the Nineties had nothing of an iconoclastic air about it. As new developments tend to do, video had accentuated a preexisting condition rather than initiating an entirely new one: in Marker’s case, making the affinity of material and metaphor in his work all the more identical. ‘These images are not the substitute for my memory, they are my memory,’ Alexandra Stewart intones in Marker’s perpetually surprising 1982 master text Sans Soleil. Though Marker has been supplanted from his own experiences by the record he’s kept of them, pushed even further away by the interpolation of the filmed records of others, it can be said that his aesthetic is founded precisely upon losing images—losing proprietorship over them, seeing them taken away and transformed by each successive incarnation.”

At the indispensable Film Studies for Free, Catherine Grant has begun collecting links “to Markerian scholarly and related work online.” It hadn’t hit me before, but she also points out that we’ve lost Marker five years “to the day since the deaths of two other legendary filmmakers Michelangelo Antonioni and Ingmar Bergman.”

“Marker fought in the French Resistance and supposedly with the American armed forces during the second world war,” writes Ronald Bergan in the Guardian. “He emerged from the Parisian Left Bank intellectual climate, coming under the influence of two postwar figures, André Malraux and André Bazin, working with the latter on the theatre section of the magazine Travail et Culture, then under the aegis of the French Communist party. He wrote a novel, Le Coeur Net, published in 1950 and translated the following year as The Forthright Spirit; a book of criticism on the playwright and novelist Jean Giraudoux; poems and short stories; and film reviews for Cahiers du Cinéma. But it was his lucid and committed leftwing documentaries, all of which he wrote and many of which he photographed, made from 1955 to 1966, that established him as a major film-maker. It was during this period that the poet Henri Michaux proclaimed: ‘The Sorbonne should be razed and Chris Marker put up in its place.'”

Libération posts a rare interview with Marker conducted for the paper by Samuel Douhaire and Annick Rivoire in 2003. And Film Comment‘s posted an English translation.

Diego Lerer‘s remembrance is in Spanish; and he points us to Marker’s YouTube channel.

David Ehrenstein posts quite a roundup of texts, clips and films, adding comments as he goes.

Glenn Kenny posts a passage from Marker’s essay, “A Free Replay: Notes on Vertigo.”

Mark Fisher for Mute in 2002: “Six Re-Views of Chris Marker: The Art of Memory.”

The AV Club‘s Scott Tobias notes that Marker “also specialized in unique profiles of major filmmakers and public figures, including Fidel Castro (1961’s Cuba Sí), and the master directors Andrei Tarkovsky (1999’s One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich) and Akira Kurosawa (1995’s AK, which caught him shooting his epic Ran). Throughout the 90s, Marker shifted into multimedia installations and cutting-edge technological experiments, keeping up the prolific pace and restless innovation that marked a half-century of artistry.”

Robert Davis in 2005: “Owls at Noon is not a single film but a series, what Marker describes as a ‘subjective journey through the 20th century,’ beginning with World War I. What’s showing at MoMA through June 13 is the first installment, called Prelude: The Hollow Men, a meditation on T.S. Eliot’s poem of the same name, written in 1925 in the wake of that war. Marker takes Eliot’s evocation of a shapeless, colorless, purposeless existence and applies it to the war’s stunned-silent aftermath, the lull and those that came later, as if the 20th century isn’t so much defined by its wars but by the brevity of the pauses between them.”

Srikanth Srinivasan’s Letters from Siberia collects clips, films and video by Marker. Via Emissions in the Dark, where you’ll find many more links to more viewing, such as Agnès Varda‘s fairly recent visit to Marker’s studio, and reading, such as Craig Keller’s translation of Marker’s essay accompanying Leila Attacks and J.G. Ballard on La jetée.

When Giampaolo Bianconi heard the news today, he “guided my generic male goth avatar to Ouvroir, Marker’s Second Life island chain,” he writes for Rhizome. “Ouvroir is devoted to monuments, art, eclectic means of transportation, and, of course, Monsieur Guillaume. It can be accessed at the coordinates 187, 61, 39. In 2010, Marker made Ouvroir, the movie, featuring Guillaume’s wanderings through the space.” Bianconi presents several screengrabs.

In 2003, special midsections on Marker ran in the May/June and July/August issues of Film Comment, and many of those features are now going online for the first time. The package was introduced by Chris Darke: “It seems to me, and evidently to all the other writers in this two-part dossier, that the whispers have now reached such a pitch that the question ‘Who is Chris Marker?’ may well be worth posing anew.” Also online so far is the previously mentioned Douhaire and Rivoire interview, Catherine Lupton on Marker and digital technology, Sam Di Iorio on Le Joli mai, Darke on early and “lost” Marker films, Paul Arthur on the influence of experimental Soviet cinema on Marker, and Kent Jones on the Immemory CD-ROM (1998).

Updates, 7/31: “His last film appears to have been a short about the history of cinema, commissioned as a trailer for the 50th anniversary of the Viennale Film Festival in October,” notes Dennis Lim in the New York Times. “The film is scheduled to be shown at the Locarno Film Festival on Saturday. Mr. Marker gave one of his final interviews—in 2008 to the French magazine Les Inrockuptibles—through the virtual medium of Second Life. In response to a question about pseudonyms as masks, he said: ‘I’m much more pragmatic than that. I chose a pseudonym, Chris Marker, pronounceable in most languages, because I was very intent on traveling. No need to delve further.'”

“Before sampling and before blogs, Marker cultivated an aesthetic based on referentiality and visual and literary quotation,” writes Jaime Wolf for Good (via Movie City News), where he especially recommends The Last Bolshevik, “about the Russian filmmaker Alexander Medvedkin, through whom we see the tragic failure of Soviet communism. Progressive without being programmatic, Marker has written: ‘If I ever had a passion in the field of politics, it’s a passion for understanding. Understanding how people manage to live on a planet like ours. Understanding how they seek, how they try, how they make mistakes, how they get over them, how they learn, how they lose their way…. That immediately put me on the side of the people who seek and make mistakes, as opposed to those who seek nothing, except to conserve, defend themselves, and deny all the rest.'”

“For Marker, memory isn’t passive; it’s an act of resistance—the edge that cuts a path into the future—and the effective work of memory is the very definition of art.” The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody: “Marker was a master of film editing—the part of the filmmaking process that Jean-Luc Godard, another master editor and memory-artist, defined as holding past, present, and future in one’s own hands… In his 1978 film A Grin Without a Cat—his vast and rueful look at what the events of 1968 actually were, and why they proved to be of so little consequence—Marker gathers an extraordinary set of documentary film clips and, assembling them along with his trenchant, provocative text on the soundtrack, brings them back from the dead. He infuses them—and, through them, history itself—with a shocking new energy. It’s as if his memory-piece—a memorial for dreams that died—actually reanimated the dreams and, by locating their traces in largely forgotten actions, offered a surprisingly practical map for making a glimmer of a stifled utopia burst forth with a new brilliance.”

Kodwo Eshun recalls a visit he made to Marker’s studio in March 2010:

How tall he was, 6ft 3 at least

How sunken his cheeks

His eyes, brown, perhaps, locked yours and held them

His watch, with the giant Obama face, two sizes too large for his thin wrist

[…]

Obama commemoration magazines sliding off the chair before he could move them

Small wooden owls hidden in the alcoves of wooden shelves

A book titled Vertov Z to A

I recall the stack of DVDs—Overlord, the Russian version of Hamlet, Le Tombeau d’ Alexandre—each with its own home made screen grabbed, printed cover, which he pressed into my hand before leaving

“One day,” recalls Howard Rodman, “sometime deep in the last millennium, I had the good fortune to be on the receiving end of a phone call from the filmmaker Jean-Pierre Gorin telling me not to make any plans for the next day, and if I had plans, to cancel them. Why, I asked. Because, he said, we’re going to visit Chris Marker. That was all he needed to say.”

“I’ve only seen eight films from his prodigious output, but each of them are more than just films to me: they’re signposts of my own cinephilia.” San Francisco-based Brian Darr walks us past each, describing the impact, and then arrives at the “sentimental favorite”: “It’s called Junkopia, and though running only six minutes in length, it has two credited co-directors, both local filmmakers who had worked on Apocalypse Now for Zoetrope Studios, the local film company which Marker visited during the shooting of Sans Soleil…. Growing up here in the 70’s and 80’s, I fondly recall every time I rode in a car toward Contra Costa County and beyond, the highlight of the drive was the stretch of bayside highway where artists built giant animals and other structures our of driftwood and similar found materials.” Junkopia documents these Emeryville mudflat sculptures and “seeing it in its native 35mm can’t be beat; I’m lucky to have done so twice.”

“Chris Marker’s films were, and still are, almost impossibly ahead of their time,” writes Zachary Wigon for Filmmaker. “The isolation of the formal elements of cinema (image, speech and music) in La Jetée; the juxtaposition of fictional cinematic history with documentary footage of actual history in Le Fond De L’Air Est Rouge; the exploration of the mysteries of time, space and memory through a few travelogues in Sans Soleil—all formally ingenious ways of telling a story onscreen that have lost none of their resonance and power, nor their originality.”

“Marker’s death during the Olympics is not without a certain poignancy since he twice used the games as a backdrop,” notes Graham Fuller at Artinfo. “Olympia 52, shot in 16mm 60 years ago in Helsinki, was his first film. The Koumiko Mystery (1965), filmed at the time of the 1964 Olympiad, is based on an interview with a modern Tokyo woman that shows how globalism had eroded the Japanese national identity.”

Adrian Curry points us to the Petite Planète series of travel books Marker edited while working for Paris’s Editions du Seuil publishing house in the 1950s.

New additions to those Film Comment dossiers: Howard Hampton argues that “what The Last Bolshevik demonstrates through its poignant saber-wit is what is missing from Godard and Debord—the tricky integration of the aesthetic, the historic, and the personal.” Plus, Michael Almereyda on Remembrance of Things to Come (2001) and Olaf Möller on Marker and Japan.

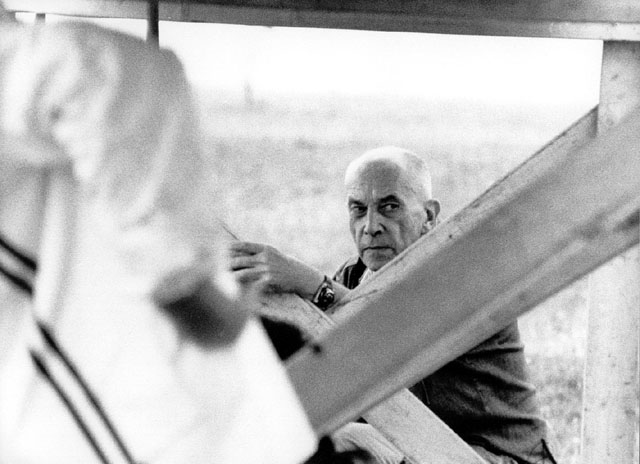

“Even though he said NO PICTURES, someone did take this picture surreptitiously.” In 1987 at Telluride. Tom Luddy shows us the photo and tells us the story at indieWIRE.

Updates, 8/1: From Elaine Woo in the Los Angeles Times: “Critic Pauline Kael called La Jetée ‘very possibly the greatest science-fiction movie yet made.’ Film critic and historian David Thomson went further, declaring in a 2002 article in the British newspaper the Guardian that La Jetée could be ;the one essential movie ever made.'”

The Peter Blum Gallery is hosting 45 photos Marker snapped over the past decades.

Dennis Grunes collects all his reviews of Marker’s films. Bookmark that page.

On Sunday, August 26, “Light Industry is hosting a free, all-day screening of his films, with introductory remarks and remembrances by Paul Chan, Tom McDonough, Molly Nesbit, Martha Rosler, and Jason Simon, among others.”

Updates, 8/2: Light Industry posts the full version of Chris Marker’s “A Free Replay: Notes on Vertigo” from the June 1994 issue of Positif.

“For all I thought I knew and admired about Marker’s work, from the touchstones of La Jetée and Sans Soleil, up to the improbable Immemory CD-ROM, Stopover in Dubai stopped me cold,” writes Greg Allen. “But not (just) because of the content, though it is chilling. Stopover in Dubai is the meticulous reconstruction of a Mossad hit squad’s surreptitious mission to assassinate Hamas military commander Mahmoud al-Mahbouh in his hotel room on January 19, 2010. The entire thing plays out silently, via CCTV surveillance video from all over the city.”

Updates, 8/3: Bill Horrigan of the Wexner Center for the Arts: “We’d been immensely fortunate to have worked with Marker on a number of projects large and small beginning with the presentation of his Zapping Zone installation in 1991, and followed by two ambitious commissioned exhibitions: Silent Movie in 1995, which would go on to tour to dozens of cities around the world (Marker only saw it several years later, when he took a train to Brussels to have a look), and the Staring Back exhibition in 2007, the first photo exhibition he’d ever agreed to. It felt satisfying that both of these projects were grounded in and eventually blossomed through the constant exchange of letters, the literary form with which he’s indelibly associated. That communicating through letters seemed to be one of Marker’s primal, unquenchable instincts effortlessly belies the idea of reclusiveness; he seemed to me passionately engaged with other people, but on his own terms, which proved immensely flattering to anyone participating in those engagements. Since the early 1990s, I’d been able to spend time nearly every year with him in Paris, usually within the overwhelming and bewildering enchantment of his lairs on the rue Courat (an unfashionable neighborhood he liked in part because it was where the Paris Commune made one of its bloody last stands) but sometimes elsewhere, and once at a café in the Palais-Royal, in the company of our great friend, the writer Molly Nesbit, an encounter I recall exactly because within the ritual exchange of presents and talismans, Marker passed to me a photograph of himself, a gesture even now I find as moving as it is mysterious.”

Thanks to Karl, who left a comment below, pointing us to the last interview conducted with Marker, pop’lab‘s from 2009 (and in French).

Marker, from the limited edition of his book Passengers (2011): “‘The apparition of these faces in the crowd / Petals on a wet, black bough‘ … The short unforgettable poem by Ezra Pound was my first idea of an epigraph for another photo exhibition, Staring Back. Then I decided to drop the epigraph. Too easy to shelter yourself behind a great poet, like a metaphorical bulletproof jacket, methought. Please note that I didn’t mention that repressed idea to anyone. Then came the first revie