“Almayer’s Folly, the great Belgian-born film-artist Chantal Akerman‘s first narrative feature in seven years (playing New York for a week at Anthology Film Archives), is a brilliant, wayward mash-up suggesting European colonialism as a madman’s fantasy—namely a white father’s hopeless passion for his mixed race daughter.” J. Hoberman at Artinfo: “The movie’s title, premise, and major characters are taken from Joseph Conrad’s first novel. The dreamlike fluidity was, according to Akerman, inspired by F.W. Murnau‘s last film Tabu—co-directed with Robert Flaherty and itself a mash-up of documentary and fiction. Conrad’s story is transposed from the 19th-century height of European empire to its mid 20th-century collapse; formerly French Indochina stands in for ‘Malaysia’; the dialogue is delivered in a medley of languages; the psychology mixes Sigmund Freud and Franz Fanon with elements of the filmmaker’s own family drama.”

The film “opens with a deep night image of the sea, the beacons of barely visible boats playing across the water,” writes Amy Taubin for Artforum. “Akerman’s last major fiction film, La Captive (2000), concludes with a similarly nearly blacked-out image of water. The two films have other elements in common. Both are modernized and very free adaptations of novels. La Captive is derived from the Albertine sections of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Almayer’s Folly from Joseph Conrad’s debut novel of the same name. The films share a lead actor, Stanislas Merhar, who, in both, plays a man obsessed to no avail with a dark haired, enigmatic young woman. What makes Almayer’s Folly different from any other Akerman film, however, is that it is set in the natural world, indeed, in a jungle resistant to human intervention, especially by colonizing white men…. The world of Akerman’s films, including the musicals, have been distinguished by their detailed, nearly ethnographic realism. La Captive moved toward expressionism—a darker, more fevered depiction of subjectivity. Almayer’s Folly goes even further in this direction.”

“A poet of displacement, Chantal Akerman has been alienating audiences for decades, and cinema is all the better for it,” declare Reverse Shot editors Michael Koresky and Jeff Reichert. “Now that her 1975 perception-altering masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles has finally been receiving widespread critical approbation, appearing at number 35 on Sight and Sound‘s 2012 list of the greatest films ever made, perhaps more viewers will be more willing to seek out her films, which are finely, obsessively calibrated yet feel impulsive and spontaneous, works of shifting forms set in inalterable landscapes.” And Almayer’s Folly features “perhaps one of the greatest shots to ever close a film.”

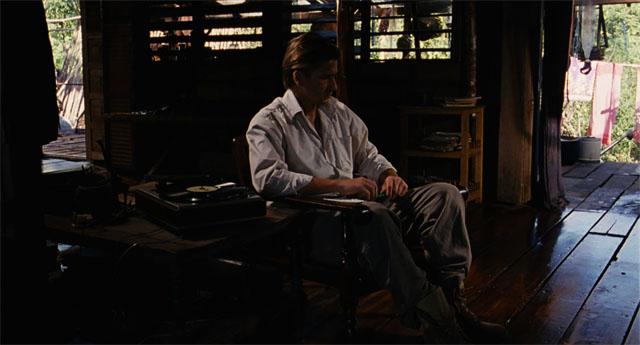

“Almayer’s Folly is a quiet epic that’s relatively thin on plot,” writes Bilge Ebiri. Nina (Aurora Marion) is “the daughter of Almayer (Stanislas Merhar), a European trader living along a river in East Asia married to Zahira (Sakhna Oum), the adopted daughter of the wealthy tycoon Captain Lingard (Marc Barbe). Almayer’s a broken man, given to quietly moping around his ramshackle home nervously despairing about the state of his affairs and the future of his daughter. (Merhar isn’t the most of charismatic actors, but he lends the character a strange, quiet fidgetiness that serves him well.) He lacks backbone or resolve: Though he adores his daughter and can’t bear to be separated from her, he allows Lingard to take her away to put her in a boarding school closer to civilization. The novel, though short, is a bit more detailed about the politics circling around the traders and smalltime despots living along the river. (The book takes place in Malaysia; the film seems to keep the setting uncertain.) The film feels like it’s going for something more universal: It’s less about the characters’ circumstances and histories and more about a strange existential truth.”

“What Akerman has done here,” writes Jesse Cataldo in Slant, “is locate the most interesting plot thread in a seemingly outmoded novel, trimming it to nurture the story of a girl born with one foot in two worlds, and with no special desire to belong to either. So while she barely speaks, Nina has other means of expression, metaphorically associated with the power of the forest, a force that’s less primeval and destructive than ever-regnant; Almayer’s expectation of control seems laughably flimsy, at the mercy of a giant river a pulsating jungle. This means that while Almayer’s Folly is a story of waxing and waning forces, an idea enforced by the repeated motif of a pale moon shadowing the water, the elder Almayer’s decline is not a downfall as much as the necessary consequence of his hubristic transgressions: As he progressively wastes away, Nina becomes more beautiful and suffused with life.”

The New Yorker‘s Richard Brody: “Sending her camera gliding languidly into the noonday shadows of a rotting shack, darting dangerously through heavy marshland foliage, or jaunting past city lights from the back of an open-air bus, Akerman embraces the rapturous but desperate beauty of the countryside and the chill of the metropolis.”

“Typically for Akerman, it’s an intensely rhythmic, brooding, and contemplative movie, but the iconography of maddened white men lost in the Torrid Zone wilderness never gets old,” writes Michael Atkinson in the Voice.

“Akerman’s formal control is, as always, astounding,” writes Keith Uhlich in Time Out New York. “Long takes abound, and the sound design, with its symphonic mix of chirping creatures, ambient buzzing and otherworldly music cues, is so immersive that you can almost feel the oppressive humidity of the occidental setting.”

“Akerman creates a fly-buzzed pocket out of time, in which the entire colonial enterprise seems to be collapsing into heat paralysis,” writes Benjamin Mercer in the L.

In the New York Times, Nicolas Rapold suggests that “it seems no accident that Almayer’s torpor, once a heartache, spreads like tendrils throughout the film. This effect of his exile is as intense as the excitement, despair, reflection or disconnect in Ms. Akerman’s previous, personally felt studies of travelers abroad, from Les Rendez-Vous d’Anna and News From Home to D’Est and Là-bas. Almayer’s Folly is not friendly terrain to traverse; like some sinister version of Proust, it is a prolonged fever dream that ultimately yields madness.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.