“Some of today’s top Mexican directors refer to Carlos Reygadas as ‘the maestro,'” begins Geoff Andrew in Time Out London. “His 2002 debut Japon reminded many of Tarkovsky; Battle in Heaven was proudly metaphorical and provocative; Silent Light borrowed blatantly from Dreyer’s Ordet. His latest continues in the same emphatically serious vein: some claim it alludes to the films of the Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul and to Sokurov. The Latin title (‘after the darkness, the light’) evokes some sort of parable, and the overall thrust of the narrative, with its elements of crime and punishment, waywardness and redemption, dysfunctionality and diabolical intervention, verges on the spiritual and moralistic.”

Post Tenebras Lux is “a congealed Jungian stew that went down to a chorus of boos at the Cannes film festival,” Xan Brooks tells us in the Guardian. “Juan (Adolfo Jiménez Castro) and Natalia (Nathalia Acevedo) are an artistic middle-class couple with two adorable toddlers and a big house in the mountains that is tended by a team of unruly rustic handymen who operate out of a corrugated-iron hut in the valley below. At one stage, Juan and Natalia jet off for an up-scale sex holiday in Europe, where the rooms in the bath-house are named after Hegel and Duchamp. At another Juan hits his dog so hard that the animal dies. He feels awful about this, though his wife is sanguine. ‘You’re doing it less and less,’ she assures him. Along the way Reygadas throws in some arresting images and haunting scenes, such as the daughter’s dream of the waterlogged field, or the CGI Satan, red as a tandoori chicken, who comes to spook the son. There is no doubt the director is leading us somewhere, all the way to the deathbed, where the light finally breaks through. If only the route wasn’t quite so rocky and circuitous. If only he’d take those damn beer glasses off the camera lens.”

Those “Beer Goggles,” as Simon Abrams calls them at the Playlist, are used for “POV shots [that] are ambiguously peppered throughout the film, and are never explicitly attributed to a single character. But considering that these POV shots flit about innocent children and adults talking about sin, over-indulgence and violence, and the Devil is literally shown stalking around in the film’s first post-opening credits scene, it’s safe to assume that Reygadas is showing us the world through the Devil’s ambivalent eyes. To wit, Post Tenebras Lux is singularly strange, though never thoughtful or especially impressive.”

“Formally, it’s a film in the vein of Tarkovsky’s Mirror and Malick’s The Tree of Life, in that plunges you into a miasma of primal and dumbfounding images that crash and overlap with one another like mighty breakers.” David Jenkins for Little White Lies: “They remain enticing and alluring, and occasionally intense: you’re on the side of the film and really want to arrive at that hallowed shot or edit or line of dialogue that at least offers the suggestion of some kind of transcendent cohesion. On first viewing, there’s something about it that repels you from wanting to take the time to decode it. Many of its individual scenes can be counted among the most sensational to appear at this festival, but stunning scenes do not a satisfying and complete work make, and it pains us to say that Post Tenebras Lux leaves you in a state of chilly bemusement rather than breathless rapture.”

“The film’s strangeness lies not only in its extreme fragmentation,” writes Jonathan Romney for Screen, “but in its visual execution too; it’s shot in Academy ratio, often using a wide-angle lens that distorts, blurs and magnifies the imagery at the edges. Alexis Zabé’s vividly beautiful photography variously makes the images seem spontaneously caught, or deliberately framed and fixed in a video art manner – and it could be argued that this film has much more in common with gallery video than with most contemporary theatrical art cinema.”

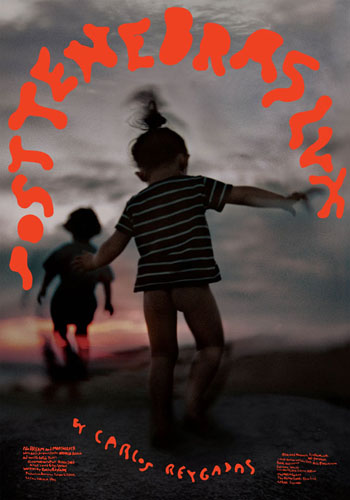

“Ever since Silent Light, Reygadas’s talent for capturing the many-toned nuances of landscape has been second to none,” writes Jay Weissberg in Variety. “The opener is a perfect example, as his own daughter, toddler Rut Reygadas, runs around a vast muddy field at stormy twilight. Several elements make the sequence extraordinary, especially the way the cacophonous dogs, cows and horses around the cute moppet take on a feral quality that vividly conveys the disturbing jumble of animalism and innocence lying at the heart of nature and the human condition. Considering the pic is described as a semi-autobiographical work, it’s not hard to imagine the scene reflecting Reygadas’s paternal concerns as he watches his vulnerable daughter progress through primal childhood. Some may feel that throwing lightning and thunder in as well is a bit much, but there’s no denying the beauty here.”

“For such a wildly expressive movie, Post Tenebras Lux is also resoundingly hollow,” finds indieWIRE‘s Eric Kohn.

Updates: “Obviously, a film like this is what it is, and there’s no real point in complaining that it doesn’t make sense or fulfill expectations,” writes Mike D’Angelo at the AV Club. “Whether you roll with it will depend largely on how entranced you are by its surface, and on that score my own reaction was decisively mixed…. And a lot of the film is just pokey and uninvolving, as we never get a sense of who any of these people are, yet bear witness to plenty of their banal interactions. Whenever Reygadas throws in a coup de cinéma—and I’m defining that broadly, to include e.g. a lovely moment in which a woman serenades her ill husband with Neil Young’s ‘It’s a Dream’ on the piano—he confirms his mastery in spades. But there are just too few of them here, and they add up too little.”

“You’re either willing to meet the movie on its level or you’re not,” writes David Fear in Time Out New York, “but if you can tune in to Reygadas’s frequency, the result is spellbinding: a lyrical, lysergic look on various states of coming together and falling apart that’s both upsetting and oddly soothing.”

“Suspicions that the critically-lauded, award-laden Mexican is, in artistic terms, an emperor clad in exquisitely invisible garments will only crystallize further thanks to Post Tenebras Lux,” argues Neil Young in the Hollywood Reporter, where he calls the film an “offensively self-indulgent cubist folly.”

Update, 5/25: “While kinetic movement and wonder define Post Tenebras Lux‘s impressive prologue, stagnation and rot permeate the rest of the film, the product of an overt sense of evil in mankind.” At Press Play, Glenn Heath Jr. suggests that Reygadas “expands the anarchic sense of time and space he first explored in his loony short for Revolucion into an entire film. Nothing adds up in this mostly maddening cinematic experience, but everything feels connected by the same ethereal view of environment, in the way characters languish, and in the nuances of a shifting world half-remembered.”

If inscrutability were the measure of success, Post Tenebras Lux would be the most successful film of all time,” writes Budd Wilkins at the House Next Door.

Updates, 5/27: “Themes of banal family life, boyhood, soured innocence, sin and self-sacrifice color this visually sublime cinematic experiment,” writes Ryan Lattanzio at the Evening Class. “I mean ‘sublime’ in the Romantic-era sense of the expression, as the film—with its dreary, waterlogged landscape sequences, its fuzzy POV shots and high levels of aesthetic artifice—captures nature’s ability to exhilarate us, and to terrify us.”

“One way to read the film is as a prelude to a man’s death—a sort of Mexican Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives.” Time Out Chicago‘s Ben Kenigsberg: “But the class tract that makes up much of the movie is so disconnected that, as a a colleague remarked, it could have been re-edited in any order.”

Dennis Lim talks with Reygadas for the New York Times: “The other day someone asked me whose films I’m looking forward to. And I said I care about Loznitsa [in competition with In the Fog], Seidl [Paradise: Love] and Omirbayev [whose film Student is in the Un Certain Regard section]. One thing that annoys me: why is a man like Omirbayev not in competition? It’s not good for cinema. I understand there have to be films with stars. But how many films are there in competition this year about cinema, by people trying to make cinema? Kiarostami, Seidl, Carax, probably four or five or six.”

And Reygadas has won the Prix de la Mise en Scene (Best Director).

Update, 5/29: Anna Tatarska talks with Reygadas here in Keyframe.

Update, 6/1: Anna Bielak interviews Reygadas for Slant.

Cannes 2012 Index: a guide to the coverage of the coverage. For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.