“The center holds amidst all the razzle-dazzle and razzmatazz of Baz Luhrmann’s endlessly extravagant screen adaptation of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s imperishable The Great Gatsby,” begins Todd McCarthy in the Hollywood Reporter. “As is inevitable with the Australian showman who’s never met a scene he didn’t think could be improved by more music, costumes, extras and camera tricks, this enormous production begins by being over-the-top and moves on from there. But, given the immoderate lifestyle of the title character, this approach is not exactly inappropriate, even if it is at sharp odds with the refined nature of the author’s prose.”

Variety‘s Scott Foundas notes that Luhrmann’s Gatsby “arrives six months after its originally scheduled December release date but maintains something of a gussied-up holiday feel, like the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade as staged by Liberace. Indeed, it comes as little surprise that the Aussie auteur behind the gaudy, more-is-more spectacles Moulin Rouge and Australia has delivered a Gatsby less in the spirit of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel than in that of its eponymous antihero—a man who believes bejeweled excess will help him win the heart of the one thing his money can’t buy.”

“Releasing in the US on May 10 before serving as the opening night film at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, The Great Gatsby doesn’t lack for star power thanks to Leonardo DiCaprio, Tobey Maguire and (to a lesser degree) Carey Mulligan and Joel Edgerton,” adds Tim Grierson in Screen Daily. “Working with several of his frequent collaborators—including cowriter Craig Pearce, production designer and costume designer Catherine Martin, and composer Craig Armstrong—the director has fashioned a striking period piece that emphasizes the 1920s’ freewheeling energy and boundless enthusiasm in the wake of an economic boom and World War I’s end, not to mention a strain of rebelliousness in response to Prohibition. As he’s done in the past, Luhrmann isn’t aiming to re-create a period precisely—rather, he wants to make a bustling, comic-book exaggeration that amplifies his audience’s collective impression of a bygone era.”

For Anne Thompson, “this is the kind of film where you hum the sets.” Profiling Luhrmann and Martin for the New York Times, Charles McGrath notes that this new adaptation has been “shot in 3D and includes such non-Fitzgeraldian elements as a soundtrack produced in collaboration with Jay-Z and songs by Beyoncé, Fergie and Jack White; a lengthy near-orgy near the beginning and party scenes that might have taken place at the old Studio 54; and a framing story that has the novel’s narrator, Nick Carraway, writing The Great Gatsby while being treated for ‘morbid alcoholism’ at a sanitarium modeled after the Menninger Clinic. Mr. Luhrmann, 50, insisted that he originally conceived of Gatsby as drawing-room drama, and that the person responsible for making the film ‘epic’ was really F. Scott Fitzgerald. ‘That damn genius goes and compresses the book, and then you’ve got to go blooey,’ he said.”

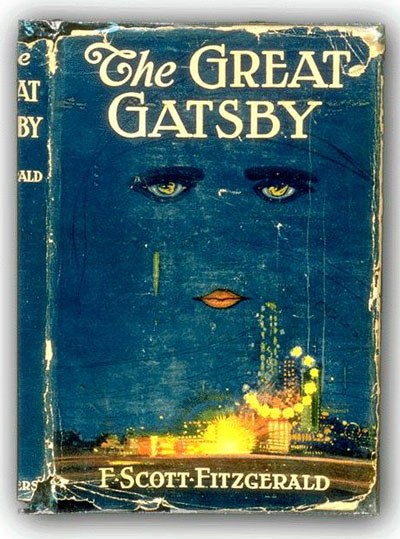

Sarah Churchwell, whose book Careless People: Murder, Mayhem and the Invention of The Great Gatsby will be out next month, notes in a lengthy piece for the Guardian that “over the past two years, both The Great Gatsby and its author have been seeing a marked resurgence of interest. In the last 12 months in Britain alone, there have been stage versions at Wilton’s Music Hall and the King’s Head theater in London, the eight-hour reading, Gatz, was staged by the American Elevator Repair Company last year to rave reviews, and the Northern Ballet‘s dance adaptation will open soon at Sadler’s Wells. Some of Fitzgerald’s long-overlooked poems, letters and stories are suddenly being published and are circulating online. Several new books are in the works, one about The Great Gatsby‘s enduring appeal, and two about Fitzgerald’s time in Hollywood, while my own book, which traces the genesis of The Great Gatsby, is about to be published. Gatsby has been thoroughly inspected and crawled over, lifted up and shaken out for every last detail it can surrender to its fascinated readers, but this remarkable novel has some surprises left.”

It “began life as Trimalchio in West Egg, and was, for a short while, to be called Under the Red White and Blue, before Fitzgerald settled on the now iconic title,” writes Ed Symkus for the Boston Globe. “It got mixed reviews upon publication (though it was championed by T.S. Eliot and Edith Wharton) and only sold about 20,000 copies in its first year. But in 1926 there was both a successful Broadway stage adaptation by Owen Davis, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1923 for his play Icebound, and a silent feature film by journeyman director Herbert Brenon. According to a letter from Zelda Fitzgerald to her daughter Scottie, as reported recently in the Huffington Post, the film was ‘rotten and awful and terrible and we left.’ … That 1926 movie, which has been lost except for a trailer that somehow found its way to YouTube, was the first of five films based on the book.”

In PopMatters, John Coffey notes that, when Paramount’s version starring Alan Ladd appeared in 1949, “the novel had not yet reached the status of vaunted literary masterpiece, and was instead best remembered as a jazz age story with a major character who has mob connections. Despite the fact that the gangland elements in the novel were mostly only hinted at, this film version winds up as a gangster movie.”

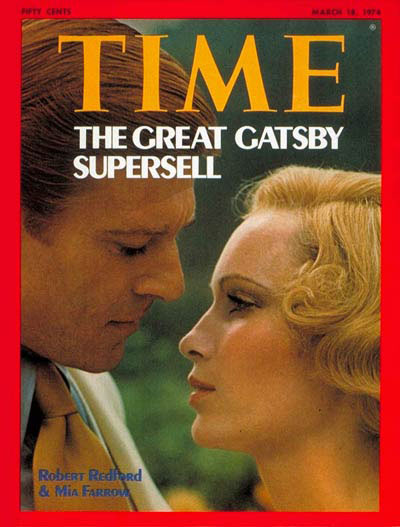

Then, of course, there’s the 1974 extravaganza. “Is the Redford-Farrow Gatsby as lousy as its reputation?” asks Bruce Handy in Vanity Fair. “Or have four decades of perspective revealed it to be a misunderstood gem? I was hoping for the latter, but the former proved to be the case, though the movie stumbles in revealing ways. I hope Luhrmann studied it closely…. Beyond casting or direction, the 1974 film’s biggest fault lies in treating Gatsby as a grand, doomed romance when the novel is really a shrewd, streamlined near satire about a group of characters who are either nasty pieces of work or foolish or both. It’s wised up and funny and tough, more Neil LaBute than Nicholas Sparks.”

Can’t help but note this bit from Peter Bart, who looks back to 1974 for Variety: “The hottest writer around, Truman Capote, was hired to adapt the novel, but Capote was drinking heavily at the time and his script turned out to be a mere re-typing of Fitzgerald. Francis Coppola was then recruited for a tab of $350,000 and delivered a superb screenplay; indeed, the possibility of another Coppola-Brando co-venture was intriguing with Brando playing an older, brooding Jay Gatsby. Both, however, still harbored post-Godfather resentments and a deal didn’t come together.”

In 1973, Paramount asked screenwriter Robert Towne if he might try his hand at an adaptation. HitFix‘s Drew McWeeney: “He turned it down, and later described that decision by saying, ‘I felt it was a very chancy thing to attempt. A lot of what was in the novel was by suggestion. So much of it was in prose and so much of it was utterly untranslatable, and even if you could translate it, I thought it would be a thankless task and you’d just be some Hollywood hack who fucked up a classic. I felt that I had a lot to lose and very little to gain. That whole book is a mirage.’ He turned out to be dead right when it came to the Robert Redford version, and I just recently re-read the Mad magazine parody of that film. What surprised me was how much of that parody still feels accurate and on-the-nose for this new version. It suggests to me that this is one of those texts that simply doesn’t make the jump.”

David Denby‘s review of Luhrmann’s adaptation is tucked behind the New Yorker‘s paywall, but Richard Brody‘s posted a few pre-viewing thoughts: “I’ve read the book many times and have always been fascinated by it, as much for what it isn’t as for what it is, as much for what it reveals about F. Scott Fitzgerald’s obsessions as for what it emphasizes about its time—and for what its enduring popularity reveals, as well. The story of a man who makes a fortune, buys a mansion, and becomes Long Island’s most profligate host, all in the hope of prying a woman he loved and lost five years earlier away from her husband and into his life, is a vision of a rhapsodic and doomed romanticism that both captures the elusive shimmer of the so-called Jazz Age and rides on the back of another literary generation.”

“In 1925,” writes former Observer literary editor Robert McCrum, “Gatsby was ahead of its time, and almost too prescient. Now, it seems perfectly in harmony with the deepest and darkest chords in American life. That’s why, for some, including this writer, it remains the greatest American novel of the 20th century.” And New Yorker contributor Evan Osnos argues that the novel “could hardly find a more fitting audience than in China in the opening years of the 21st century.”

Luhrmann profiles and interviews: Stephen Galloway (Hollywood Reporter), John Horn (twice in the Los Angeles Times), and Jennifer Vineyard (Vulture).

At Flavorwire, Alison Nastasi has a few suggestions for further viewing, films about the Jazz Age actually made during the Jazz Age.

Updates: In New York, Kathryn Schulz files what she calls “a minority report”: “I know how I’m supposed to feel about Gatsby: In the words of the critic Jonathan Yardley, ‘that it is the American masterwork.’ Malcolm Cowley admired its ‘moral permanence.’ T.S. Eliot called it ‘the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.’ Lionel Trilling thought Fitzgerald had achieved in it ‘the ideal voice of the novelist.’ That’s the received Gatsby: a linguistically elegant, intellectually bold, morally acute parable of our nation. I am in thoroughgoing disagreement with all of this. I find Gatsby aesthetically overrated, psychologically vacant, and morally complacent; I think we kid ourselves about the lessons it contains.”

Back to the film at hand. It’s “overkill almost every step of the way,” finds Rodrigo Perez at the Playlist. He gives it a C+.

“It doesn’t help that the cast feels like they’re in different movies—and none of them are movies you’d particularly want to see,” writes Alonso Duralde at TheWrap. “The blank and reactive Maguire and Mulligan are cast as the blank and reactive Nick and Daisy, the result being such a vortex of nothing that they threaten to disappear from the screen entirely. Edgerton perspires and chews the scenery in his best Snidely Whiplash manner, while DiCaprio has a fluctuating accent that often sounds like it’s being delivered through a mouthful of marshmallows. DiCaprio’s utterances of Gatsby’s pet endearment ‘old sport’ become more and more cringe-worthy with each repetition…. The cardinal sin of this new Gatsby is that it’s dull.”

Updates, 5/7: “Ever since the global dominance of the Transformers franchise, Michael Bay has been singled out as the reigning king of studio-produced indulgences,” writes Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn. “Luhrmann, whose attempt at old school Hollywood romance with Australia bombed hard, may not have quite the same track record for pandering to audiences’ basest sensibilities. Yet his take on Gatsby suffers the same hollow style-over-substance issues—in this case, flimsily obscured by mock allegiance to a classy text—that have assailed Bay’s movies. The difference is that Bay owns up to it.”

New York‘s David Edelstein argues that “for all its computer-generated whoosh and overbroad acting, it is unmistakably F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby…. Luhrmann throws money at the screen in a way that is positively Gatsby-like, walloping you intentionally and un- with the theme of prodigal waste.”

The New Yorker has unlocked David Denby‘s review: “Gatsby’s excess—his house, his clothes, his celebrity guests—is designed to win over his beloved Daisy. Luhrmann’s vulgarity is designed to win over the young audience, and it suggests that he’s less a filmmaker than a music-video director with endless resources and a stunning absence of taste.”

Nick Lucchesi for the Voice: “Here, in animated GIFs, are shot-by-shot comparisons from the 1974 version and the 2013 version.”

“In one of the more unfortunate segments of The Story of Film,” writes Violet Lucca for Film Comment, “Mark Cousins rhapsodizes about Baz Luhrmann’s oeuvre for nearly 15 minutes. The prolonged interview and cooing voiceover that champions Australia as a formally inventive masterpiece seems out of place in a documentary that glosses over (or completely skips) the careers of so many more prolific directors, and also because it so blandly presents one of the 21st century’s greatest purveyors of straight camp. The man who used the chorus of ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ in a pop music/cancan dance medley demands something crasser than a history lesson built out of lies through omission. Sadly, it’s the more austere version of Luhrmann that directed The Great Gatsby. There is no frame-fucking, no hyperactive repetition of small gestures, no grotesque too-close close-ups; instead, the film is simply a parade of set pieces that exhibit little creativity or his characteristic energy.”

Updates, 5/8: “Luhrmann treats the interior spaces as proscenium, moving forward and back instead of sculpting space,” writes Ray Pride at Newcity. “Stanley Kauffmann could have been predicting Luhrmann’s redundant use of 3D when writing years ago about a director’s compositional style in some forgotten street-savvy crime thriller as demonstrating a mastery of ‘the large foreground object.’ In traditional photographic composition, depth and distance are readily indicated that way, but Luhrmann adds this elemental technique to 3D, doubling down on the simple geometric differentiation of space: an oscillating electric fan in the foreground; a spoked wheel rim that frames a mechanic’s sweaty face; rainbow-edged glints from superimposed thickness of car window glass. Shockingly, sadly, in 3D, Baz don’t dance.”

“Decadent prose is transformed into a decadent filmmaking style that defies modesty in the most brutal sense,” writes Richard Larson in Slant.

For Time Out New York‘s Keith Uhlich, the problem is “Luhrmann’s Minnelli-on-acid aesthetic: The anachronistic pop-music cues, digitally augmented tracking shots and disco-globe–glittery production design don’t re-create the headiness of early-20th-century New York so much as invent a billowy fantasy otherworld in the gauzy vein of Twilight. Shorn of its quintessentially American roots, a biting tale of adult extravagance becomes insubstantially tween-aged.”

In the Voice, Stephanie Zacharek grants that “this Gatsby is a mess. But it moves, it breathes, it has color on its side, and because of that, it feels far more respectful to the source material than Jack Clayton’s dreary 1974 number.”

More from William Goss (Film.com, 5.8/10), Richard Lawson (Atlantic Wire), and Eric D. Snider (Twitch).

Updates, 5/11: “Does Baz Luhrmann dream of making Ken Russell seem as restrained as Robert Bresson?” asks J. Hoberman at Artinfo. “[G]iddy as it is, The Great Gatsby lacks the lunatic excess of Moulin Rouge! There’s nothing here to compare with the latter’s absinthe vision of Tinkerbell or Jim Broadbent’s prancing version of ‘Like a Virgin.’ … This Gatsby is beyond vulgar but, unfortunately, not far enough.”

“The problem with Luhrmann’s film is that it’s under the top,” agrees Richard Brody. “For all of its lurching and gyrating party scenes, for all the inflated pomp of the Gatsby palace and the Buchanan mansion, for all the colorful clothing and elaborate personal styling, Luhrmann takes none of it seriously, and makes none of it look remotely alluring, enticing, fun.”

“The one redeeming feature of Luhrmann’s film is that it restores some of the humor of the novel,” writes Maureen Corrigan for the New Republic. That said, he’s “pared down its acute class anxiety.”

“Look, it could have been so much worse,” sighs Bilge Ebiri in the Nashville Scene. Similarly, Ben Kenigsberg at the AV Club: “Like Romeo + Juliet (1996), Luhrmann’s version of The Great Gatsby emerges as a half-reverent, half-travestying adaptation that’s campy but not a betrayal, offering a lively take on a familiar work while sacrificing such niceties as structure, character, and nuance.”

“Every frame is sincere,” grants Matt Zoller Seitz at RogerEbert.com. “Its miscalculations come from a wish to avoid embalming a classic novel in ‘respectfulness’—a worthy goal, in theory. It boasts the third most imaginative use of 3D I’ve seen recently, after U2 3D and Hugo. It’s a technological and aesthetic lab that has four or five experiments cooking in each scene. Even when the movie’s not working, its style fascinates. That ‘not working’ part is a deal breaker, though—and it has little to do with Luhrmann’s stylistic gambits, and everything to do with his inability to reconcile them with an urge to play things straight.”

“Simply as a torrent of images and visual ideas—often magnificent and just as often idiotic—The Great Gatsby is a phenomenon not to be missed,” argues Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir. “But it isn’t The Great Gatsby.”

“The one thing that Luhrmann instinctually understands is that The Great Gatsby is packed with creepiness,” writes Paul Constant in the Stranger. “Carraway leers on the outside, looking in. Gatsby treats Daisy like a human doll, and his enormous mansion is nothing so much as a gigantic time machine with which he plans to remake the universe in his own image. Tom toys with the lives of the poor like a petulant, horny Greek god. And the modern American God is in there, too, represented as a pair of eyes on an abandoned billboard. ‘God sees everything,’ we are told a few times by characters lost in clouds of their own boozy breath. That’s because God is creepy. And then you turn around and see a theater full of people wearing cheap sunglasses staring raptly at a screen, sometimes reaching their hands out to touch the three-dimensional images that don’t really exist in front of them, like Gatsby standing on a pier trying to capture a distant green light in his hand, and Luhrmann’s obvious point grabs you by the nose and screams in your ear. This is America. We’re all creeps.”

More from Sean Burns (Philadelphia Weekly; “a cluttered, 3D muddle in which Leonardo DiCaprio happens to be amazing”), Ty Burr (Boston Globe, 2.5/4), Richard Corliss (Time), Mike D’Angelo (Las Vegas Weekly), Jesse Hassenger (L), Kimberley Jones (Austin Chronicle, 2/5), Drew Lazor (Philadelphia City Paper, B), R. Kurt Osenlund (House Next Door), Kiva Reardon (Loop, C), and A.O. Scott (New York Times).

Vanity Fair has posted Christopher Hitchens‘s piece on the novel for the May 2000 issue. And at Slate, Dana Stevens and David Haglund discuss the film, spoilers and all, while Haglund measures it against the novel for faithfulness. The movie’s also the subject of Variety‘s latest “3View.”

Updates, 5/13: The Columbia University Press blog has posted a piece by Haruki Murakami on the challenges of translating the novel: “When someone asks, ‘Which three books have meant the most to you?’ I can answer without having to think: The Great Gatsby, Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, and Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye. All three have been indispensable to me (both as a reader and as a writer); yet if I were forced to select only one, I would unhesitatingly choose Gatsby.”

For Joshua Rothman, writing for the New Yorker, the Luhrmann’s Gatsby is “lurid, shallow, glamorous, trashy, tasteless, seductive, sentimental, aloof, and artificial. It’s an excellent adaptation, in other words, of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s melodramatic American classic. Luhrmann, as expected, has turned Gatsby into a theme-park ride. But he’s done it in exactly the right way. He hasn’t tried to make the novel more respectable, intellectual, or realistic. Instead, he’s taken The Great Gatsby very seriously just as it is.”