“Andrei Zvyagintsev‘s Elena is a tale of two apartments,” begins Nick Pinkerton in the Voice. “The film is bookended by shots that look in, covetously, on a spacious chrome, glass, and marble luxury flat that might be anywhere in prosperous Western Europe. In between, it commutes to a cramped unit in some exhausted-looking, distinctly Soviet-vintage apartment block with a view of a nuclear plant. Central to the movie is the distance, physical and psychological, and the mutual resentment, that exists between these spaces.”

“Zvyagintsev is able to get most of the necessary exposition out of the way in the first five evocative minutes,” writes Chuck Bowen in Slant. “A crow lands on the barren tree outside of an expensive and expansive residence. A middle-aged woman (the unforgettably wonderful Nadezhda Markina) awakes to the sound of an alarm clock. Tellingly, she’s sleeping on a couch. She takes a few deep breaths, resigns herself to the approaching day in a fashion that’s familiar to the deeply unhappy, and begins to comb her hair. She starts the breakfast tea and coffee and, more tellingly, proceeds to a bedroom to nudge an older man (Andrei Smirnov) awake who’s soon revealed through body language to be, at the least, a live-in lover. Eventually the couple sit down to breakfast and exchange a few pregnant not-quite-pleasantries that reveal that they’re somewhat recently married and that they mutually disapprove of how the other handles their adult child from prior relationships. We’re soon told that the woman is Elena and the gentleman is her husband, Vladmir, and it’s no accident that their association follows a series of rituals that are more characteristic of servant/master than wife/husband.”

“You are keenly aware of the distance between Elena, a former nurse from a proletarian background, and the imperious, hard-nosed Vladimir, whom she cared for while he recovered from peritonitis a decade earlier and then married.” Stephen Holden in the New York Times: “It’s not that they loathe each other. When he signals that he wants sex, she matter-of-factly obliges him…. Elena and Vladimir may live in splendor, but their upscale neighborhood is weirdly devoid of people. An ominous calm hangs over the area, except for the cawing of crows, which can be heard indoors as well as out. And the movie’s acute aural awareness of the animal kingdom within the city underscores its vision of Moscow as a jungle teeming with predatory wildlife.”

Benjamin Mercer in the L: “The director—whose first two films, The Return (2003, terrific) and The Banishment (2007, not released stateside), drew Tarkovsky comparisons, recently including their own footnote toward the end of Geoff Dyer‘s marathon Stalker recap, Zona—slides into the role of the contemporary-life anatomist here, showing the rottenness of an increasingly wealth-stratified society. As such, the rigorously composed Elena bears some resemblance to the grubbier motherland invective that has, in recent years, been imported from Russia for the American audience.”

“Elena, in its concentrated austerity, often resembles a lost chapter of Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Ten Commandments-themed Decalogue,” finds Joshua Rothkopf in Time Out New York. For Ioncinema‘s Nicholas Bell, Elena suggests “a film noir echoing Chekov’s class squabbles.”

“Even days after seeing Elena, I’m not sure how to feel about any of the characters, which I consider the highest compliment,” writes Tim Grierson for IFC. “Life isn’t simple. To capture it in all its complexity, Elena is heroic.”

Last summer, Eric Welles-Nyström attended Bergman Week on the island of Fårö and Cinespect is running a translation of his report for Rivista Studio. Zvyagintsev was, along with István Szábo and cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro, a guest speaker. “I couldn’t wait to meet Zvyagintsev. Having picked up a pirated copy of [The Return] during a high school trip to Rome in 2004 and having loved it deeply ever since, I consider Zvyagintsev to be one of the greatest modern directors. And besides admiring the distinctive style he has come to develop, I’ve always been intrigued by some of his very close resemblances to Bergman, as well: the reoccurring portrayals of weak, cowardly fathers; the strict usage of shadowless, natural light; and the lack of references to location or time, which deepens the mystique so perfectly in his first two films. Then one night, at last, after [The Return] was shown in an old, barn-turned-cinema, which had been built in the 1950s and still had its original movie posters on the walls, we were able to sit down and talk about his movies, his actors and his love for adventures—L’Avventura!”

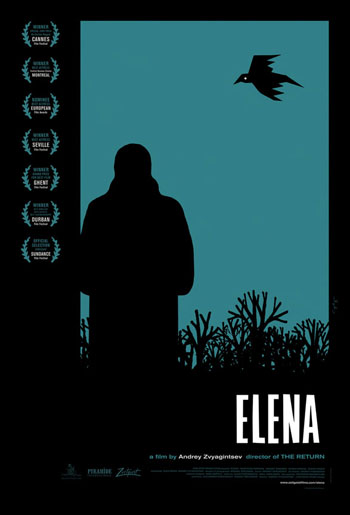

Elena is at New York’s Film Forum through Tuesday, May 29, before it starts rolling out across the country throughout the summer. Zeitgeist Films has cities and dates. Last week, Adrian Curry spoke with Sam Smith about his poster design—and about his favorite movie posters of all time.

Updates, 5/17: “Elena is didactic filmmaking,” writes Vadim Rizov at GreenCine Daily, “and in interviews, director Andrei Zvyagintsev hasn’t been shy in explicitly stating his fundamental criticism of the contemporary Russian underclass. ‘This is how they will behave,’ he noted in an interview conducted at the film’s Cannes premiere. ‘At one point we considered calling the film The Invasion of the Barbarians…. Austerely condemnatory, Zvyagintsev’s argument is convincingly apocalyptic (its original incarnation was as an English-language end-of-days drama), hypnotically rendered in slow zooms and tensely prolonged shots, making for the most visceral of jeremiads.”

Scott Tobias at the AV Club: “It’s an austere Russian drama with shades of Hitchcock.”

For Jonathan Robbins, though, writing in Film Comment, Elena “does not evoke the complex emotions that family and money stir up. It merely gestures in their direction, declaring the Russian soul sick with greed, like a doctor offering a diagnosis but no cure.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed.