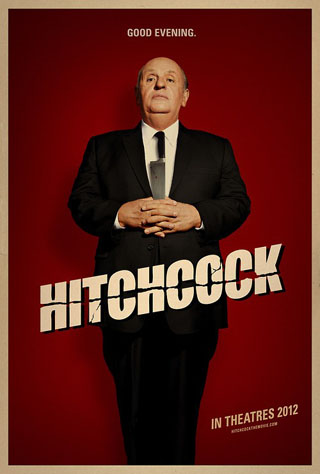

Hitchcock, with Anthony Hopkins as the Master of Suspense and Helen Mirren as his wife, Alma Reville, opened AFI Fest 2012 on Thursday, and the first reviews are coming in. We begin with Variety‘s Justin Chang: “An intriguing change of pace for helmer Sacha Gervasi after his winning 2008 docu Anvil! The Story of Anvil, this Nov. 23 release arrives in theaters just a month after the airing of HBO’s The Girl, an unflattering portrait of Alfred Hitchcock’s troubled dealings with star Tippi Hedren during production on The Birds and Marnie. While it similarly references the helmer’s attempts to manipulate the blonde leading ladies who tickled his fancy, the comparatively frothy Hitchcock offers a more sympathetic, even comedic assessment of the man behind the portly silhouette.”

“The film opens with Hitchcock speaking directly to us, Alfred Hitchcock Presents… style,” notes John Patterson in the Guardian. “He’s just enjoyed the huge success of North by Northwest and is at a loose end for projects. Offered Cary Grant in Casino Royale, he reminds his assistant Peggy Robertson (Toni Collette): ‘I just made that movie.’ His ears prick up, however, when he encounters Robert Bloch’s Freudian gore-transvestite-incest-necrophilia shocker Psycho, which horrifies everyone he shows it to, but which might give him the edge he needs in his private war with French director Henri-Georges Clouzot, whose Les Diaboliques has critics talking of ‘French Hitchcocks’ and similar rot.”

“Hitchcock, with its deep, abiding movie love and lore, plays as a can’t-miss festival crowd-pleaser,” finds Glenn Whipp in the Los Angeles Times. “Hopkins fills the master’s shoes and jowls as capably as you’d expect and his frustrations with the Production Code head Geoffrey Shurlock, agent Lew Wasserman and Paramount Pictures President Barney Balaban should resonate with many Oscar voters. ‘They just want the same thing over and over and over,’ Hopkins’s Hitch rails. ‘They’ve put me in a coffin and now they’re nailing down the lid.'”

“What could have been just insiderish stuff about budget and story disputes becomes quite entertaining,” writes the Hollywood Reporter‘s Todd McCarthy. “[T]he Hitchcocks are forced to gamble their Bel-Air home to run with the director’s hunch, increasing his sense of urgency and anxiety. Initially resistant, Alma finally throws her full support behind her husband, as she always has, revealing what eventually emerges as the film’s dominant impulse, which is to spotlight Alma Reville Hitchcock as an essential partner in her mate’s extraordinary success.”

Back to John Patterson for a moment: “All the smaller roles are neatly filled, particularly Scarlett Johansson’s Leigh and James Darcy’s Tony Perkins, the latter almost eerily resembling the original; plus Kurtwood Smith as the fuming head of the censor’s office and Ralph Macchio as screenwriter Joseph Stephano. But it lives and breathes through Hopkins and Mirren. Unlike Toby Jones’s Hitch in The Girl, which physically and vocally evoked the director very convincingly, Hopkins relies, as with his Nixon, on a few tics, some prosthetic fakery, and just lives the man, pink, pale, blinking and blimpish, held up by iron certainty in his own talents.”

“Helen Mirren’s performance as Hitch’s wife and partner Alma is flawless,” finds Twitch‘s Ryland Aldrich. “Hers seems the biggest lock for awards season recognition.” And In Contention‘s Kristopher Tapley weighs the potential for awards in other categories.

Updates: “Based on Stephen Rebello’s forthcoming book, Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho, John McLaughlin’s screenplay has been vividly realized by director Sacha Gervasi,” writes Indiewire‘s Eric Kohn. “Given a tremendous amount of credit for influencing various plot points in Psycho, Alma becomes the true star of Hitchcock, the enabler unappreciated by the man she enables, but once the movie gets drawn into this drama it loses much of the appeal generated from the tale of the production.”

Writing for Screen, Tim Grierson finds that Gervasi and McLaughlin “brandish a sly comedic streak, poking affectionate fun at the legendary director and the egos that make up Hollywood. This cheeky attitude is on display from the outset, where Hitchcock speaks directly to the camera and calmly introduces us to Ed Gein (Michael Wincott), the real-life murderer who inspired the Norman Bates character at the centre of the book Psycho that Hitchcock adapted for his film. It’s a nervy opening that leads with its dark sense of humor—it’s a shame, then, that the rest of Hitchcock doesn’t have the same sharp tonal control, too easily lapsing into overheated melodrama and, later, syrupy sentimentality.”

Update, 11/14: Lily Rothman interviews Gervasi for Time; plus, a fresh clip.

Update, 11/16: For Andrew Schenker, writing at Slant, Hitchcock‘s “confronting-of-the-personal-demons angle, which turns the film’s midsection into a half-baked psychodrama, makes an odd and wholly unsatisfying fit with the movie’s other through line: the surface-deep look at the lensing of Psycho. Essentially the film traces the evolution of the director from the witty quipster we know from reruns of Alfred Hitchcock Presents to an absolute monster: tyrannical on the set, horrible to his wife, and perpetually plagued by visions of serial killer Ed Gein, who encourages his perverse impulses, which include spying on actress Vera Miles in her changing room—before duly reverting back to a spouse-devoted decent guy. None of this is very convincing, a fact that shouldn’t prove too surprising since the film’s real interests lie elsewhere.”

Updates, 11/18: John Anderson in the New York Times on Alma Reville: “As historians and insiders have long known she played an indispensable role in the making of her husband’s movies, as a story consultant, script editor, continuity person and overall sounding board. She was his closest confidante, his most trusted ally. When the Hitchcocks met in 1920s Berlin, she was already a rising star at Ufa, the German film studio; he was a would-be production designer with an advertising portfolio under his arm. As Mrs. Hitchcock, Alma Reville became the quintessential unsung heroine. But now, being played by two prominent actresses (Helen Mirren and Imelda Staunton [in The Girl]) she is being ushered out from behind the curtain.”

“Hitch not only faced studio indifference and the perils of self-financing, but intense jealousy due to his wife’s ‘professional’ relationship with writer Whitfield (Danny Huston),” writes Pete Hammond at Box Office. “Whatever the truth of his wife’s association with Whitfield—and of Hitchcock’s admitted obsession with his own leading ladies—the suspicion leads to a showdown where Alma lets Hitch know in no uncertain terms what it is like to be in his shadow. It’s a killer moment, the most honest in the film, and Mirren knocks it out of the park.”

Update, 11/19: “I suppose I’m pretty lucky,” writes Glenn Kenny, “that the movie, which is bad (as I discuss at some length in my review for MSN Movies) is as bad as it is, because it spares me what might have been some sort of aesthetic/ethical conflict. That is, what if the movie had been engaging, entertaining, in some way valuable, while at the same time telling the same number of lies it tells, and insulting the same filmmakers it does.”

Matt Singer‘s latest Criticwire survey question: “What is the most underrated Alfred Hitchcock film?”

Updates, 11/20: Richard Brody: “Gervasi rightly suggests that Hitchcock is no mere puppet master who seeks to provoke effects in his viewers; he’s converting the world as he sees it, in its practical details and obsessively ugly corners, into his art, and he’s doing so precisely because those are the aspects of life that haunt his imagination.”

“It’s a feel-good frolic,” writes Mary Pols in Time, “which is fine for anyone who prefers their Hitchcock history tidied up, absent the megalomania, the condescending cruelty and tendency to sexual harassment that caused his post-Psycho blonde discovery Tippi Hedren to declare him ‘a mean, mean man.'”

“[T]he three extant reels of The White Shadow (1924) are now free to stream on the National Film Preservation Foundation website,” notes R. Emmet Sweeney at Movie Morlocks. “Part of the cache of rarities discovered in the New Zealand Film Archives in 2010, along with John Ford’s Upstream, The White Shadow is the earliest surviving film that Hitchcock worked on. He was assistant director, editor, scenarist and art director, the second of five films on which he was the jack of all trades for director Graham Cutts. The White Shadow was a critical and box office failure, even leading to the dissolution of its production company, but what remains is an essential document of Hitchcock’s artistic maturation, containing themes of doubling and mistaken identity that would re-emerge and deepen throughout his career. Along with the National Film Preservation Foundation, great thanks are also due to David Sterritt for his informative film notes and Marilyn Ferdinand, Farran Smith Nehme, and Roderick Heath, whose For the Love of Film Blogathon funded the recording of the fine score by Michael Mortilla.” And Fandor’s doing the hosting.

The Telegraph gets a few words with Hopkins.

Updates, 11/22: “Maybe the only way Hollywood can handle letting its customers tour the sausage factory is by shuttling us down the scenic route, giving us the illusion that we’ve seen plenty while ensuring the secret recipe remains obscured,” writes Karina Longworth in the Voice and LA Weekly. “Hitchcock is a movie about bygone Hollywood that’s distinctly a product of Hollywood circa now. It bears the influence of the kind of reality TV in which the subject’s career is the stated excuse for the show, but in terms of screen time and story line, what they actually do for a living is relevant only in that it puts them in glamorous locales and in contact with potential catalysts for stock, soapy side drama.”

Psycho is an “irreducible achievement that’s cheapened every time Gervasi wanders away from it,” writes the AV Club‘s Scott Tobias. “History is history; the rest is trivia.”

For Film.com‘s Stephanie Zacharek, Gervasi’s film “is so simplistic that it barely has any weight at all…. His Hitch is a portly, naughty cutie-pie who delights in showing off crime-scene photos to his assembled luncheon guests. What a cutup! Don’t you just want to hug him?”

“[H]orribly on-the-nose dialogue flatters those viewers who prefer to keep their sense of cinema history on fan-mag frivolous levels,” notes Keith Uhlich in Time Out New York. His example: “‘I’ve waited 30 years for you to say that to me,’ swoons Alma to a rare Hitch compliment. ‘That’s why they call me “The Master of Suspense,”‘ he quips.” To which Keith adds: “Pardon us, Mother Bates, may we borrow your knife?”

For the San Francisco Bay Guardian‘s Cheryl Eddy, though, “Hitchcock may not best the political biopic that’s its current box-office competition, Lincoln (nor will Hopkins likely upset Daniel Day-Lewis on any award-show podiums), it’s miles better than another Hopkins-starrer in that vein: 1995’s Nixon.”

More from Benjamin Mercer (L), Charlie Schmidlin (Playlist), and Bill Stamets (Newcity Film).

“While Janet Leigh (Scarlett Johansson), Vera Miles (Jessica Biel) and Bernard Herrmann (Paul Schackman) are depicted with reasonable accuracy, others don’t fare as well.” Time Out Chicago‘s Ben Kenigsberg does some fact-checking.

“Thirty-two years dead, Alfred Hitchcock this year supplanted any other pretenders to the role of the dominant icon in the history of world cinema.” At Artinfo, Graham Fuller counts the ways.

For Movieline, Nell Alk has Gervasi and his cast name their favorite Hitchcock films and scenes; Aaron Hillis has a longer chat with Gervasi for the Voice; and Gervasi talks us through a scene at the NYT.

Updates, 11/24: “The fantasy vision of Alma and Hitchcock’s marriage is one unfortunate element in a movie that doesn’t merely give creative genius a bad name, but also pathologizes it,” writes Manohla Dargis in the New York Times. “Hitchcock, you are meant to believe, was himself a little psycho and could only work from a place of madness.” All in all: “It’s fluff. But while its dim fantasies about Hitchcock and the association of genius with psychosis can be written off as silly, they also smack of spiteful jealousy.”

“To have been among the fortunate few who did see Psycho cold was a once in a lifetime experience,” writes J. Hoberman at Artinfo. “The critic William Pechter described the unique atmosphere of excited dread with spectators united before the screen in fearful anticipation. Audiences responded as though trapped on a roller coaster ride through the spook house…. Making much of Hitchcock’s genius for manipulation and reliance on Alma’s skill as an editor, Hitchcock is basically Hitchcock for Beginners.”

“Who was the real Hitchcock?” asks Roger Ebert. “I interviewed him once and haven’t a clue. The closest we’ll probably come is in the book-length conversation he had with director Francois Truffaut, but they were talking shop, not blonds.”

“The richest of [Hitchcock’s films]—Suspicion, Notorious, Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, The Birds, Marnie—are like cities,” suggests the Boston Globe‘s Wesley Morris. “There’s always some side street, some building, some statue you’ve never noticed or you’ve noticed but have never appreciated. They’re like planets, too: The centers are as complex as what’s on the surface. This is all a long way of saying that the best way to better understand the man who made those and dozens of other movies is simply to see them. There’s no case to be made for a mangy shortcut like Hitchcock. It’s all surface and formula.”

Updates, 11/25: Hitchcock “manages to be astonishingly patronizing to its principal characters,” writes Glenn Kenny in a post that rolls up a reply to Richard Brody, comments from Joseph McBride and Manohla Dargis, and passages from Robin Wood and from Truffaut’s famous interviews with Hitch. And of course, it’s launched an engaging thread as well.

“Hitchcock is less a bad film than a middling, minor one,” writes Salon‘s Andrew O’Hehir, “but it fails the standard I once heard applied to books about Proust: They have to be good enough that you wouldn’t be better off reading Proust instead. The contrast, in this case, is ridiculous.”

Still, for Jason Bellamy, “it’s no worse than your typical biopic that’s rife with oversimplification to fit real lives into a traditional dramatic structure.”

Updates, 11/26: “In a lifetime of watching movies, and a long time writing about them, I’ve rarely cared much about the psychological process of their creation,” writes Time‘s Richard Corliss. “Are directors meanies? Some, probably. Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the great and strange German filmmaker, enjoyed humiliating his performers; and I recall one actor saying that Otto Preminger, also a notorious tyrant on the set, was ‘the very worst person in the world,’ adding the caveat, ‘now that Hitler’s dead.’ Other filmmakers may be pussycats, camp counsellors, benevolent shrinks, best friends. What’s certain about top male directors, especially those lacking matinee-idol looks, is that they make movies for two reasons: to express their unique vision of the world, and to control beautiful women. On the set the actress must please her director, ‘do it again’ until she ‘gets it right’; and he must encourage, seduce or terrify his performers to make this piece of time a memorable one for the audience…. And the real Hitchcock: genius or monster, or both? While his mannerisms are obvious, his interior life remains elusive. Besides, his strategies on the set matter much less than the mordant glories he put on film.”

Jennifer Vineyard interviews Hopkins for Vulture.

Updates, 12/2: “How Toby Jones plays Hitchcock versus the way Anthony Hopkins does is ‘interesting’ for roughly the combined length of each film’s trailers,” writes Film Comment‘s Violet Lucca. “The contrasts one can tease out after that short amount of time are the same after watching both films all the way through: Hopkins fucks up the voice and Jones isn’t tall enough…. In my imagination, I swap the two actors. Hopkins’s perverse coldness complicates the quirky, cuckolded character of Gervasi’s diegesis: for 98 minutes he alternates between Helen Mirren’s Alma towering over him and having convincingly terrifying dreams of collaborating with Ed Gein. In The Girl, Jones’s goofy mugging underscores the great degree of arrested development and self-delusion sexual sadists in the workplace have. As it stands, you can watch them in chronological order (first Hitchcock, then The Girl) and imagine him transforming physically between Psycho and The Birds as his eccentricities evolve into perversion.”

“If he could see the pair of films about his life that recently landed simultaneously on the big and small screens, Hitch would probably be less offended that they depict him as a cruel, blonde-obsessed, stress-eating egotist than by the fact that they do so with such an utter lack of cinematic style,” writes Shaun Brady in the Philadelphia City Paper.

Writing for Cinema Scope, Jose Teodoro finds Hitchcock to be “at once reprehensibly tidy in its recreation of Psycho‘s behind-the-scenes drama and stupefyingly incoherent in tone…. But perhaps what’s most irksome about Hitchcock is its failure to convey very much that’s interesting about the filmmaking process.”

For the Philadelphia Weekly‘s Sean Burns, “what’s galling about Hitchcock is just how nonsensical and purposeless all the elisions and distortions turn out to be, constantly tossing aside credibility for a cheap elbow in the ribs.”

Update, 12/23: “The suggestion that the director might enjoy trying his hand at stabbing some woman —whether because of the unavailability of his mother, or Grace Kelly, or Vera Miles, or the Oscar—is never satisfactorily elaborated,” finds Jerome Christensen, writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books. “Moreover, it is the cheerful, respectful Janet Leigh who, during the shooting of the famous shower scene, becomes Hitchcock’s target as he almost surrenders to his homicidal urges. When, in a tantrum over the desultory handling of the knife by the stunt double, the director falls into a fit of stabbing the air with a butcher knife, it is reasonably shocking. But it is not shocking enough to make us suspend our disbelief that the makers of Hitchcock would have the nerve to pull a meta-murder by having the character Hitch actually kill off the character Janet Leigh. That might have been unpleasant, but it would have been the kind of genre-busting gesture that made Psycho so thrilling—it would have shattered the conventions of the biopic as satisfyingly as Psycho shattered those of the suspense film.”

For news and tips throughout the day every day, follow @KeyframeDaily on Twitter and/or the RSS feed. Get Keyframe Daily in your inbox by signing in at fandor.com/daily.