Partisan agitprop around issues of immigration, race, and the ugly truths of America’s past are never not in the news or detonating social media these days, so Fandor viewers hardly need Black History Month to underscore the continued relevance of John Sayles’ 1984 “E.T. Comes to Harlem” fable The Brother from Another Planet. Yet, the occasion also offers a great excuse to revisit the indie gem, a lo-fi sci-fi update of African American slave narratives that looks decades ahead to the Afrofuturism in recent streaming adaptations, including “Lovecraft Country” (produced by Jordan Peele’s Monkeypaw Productions) and “The Underground Railroad” (Barry Jenkins’ epic dramatization of the Colson Whitehead novel).

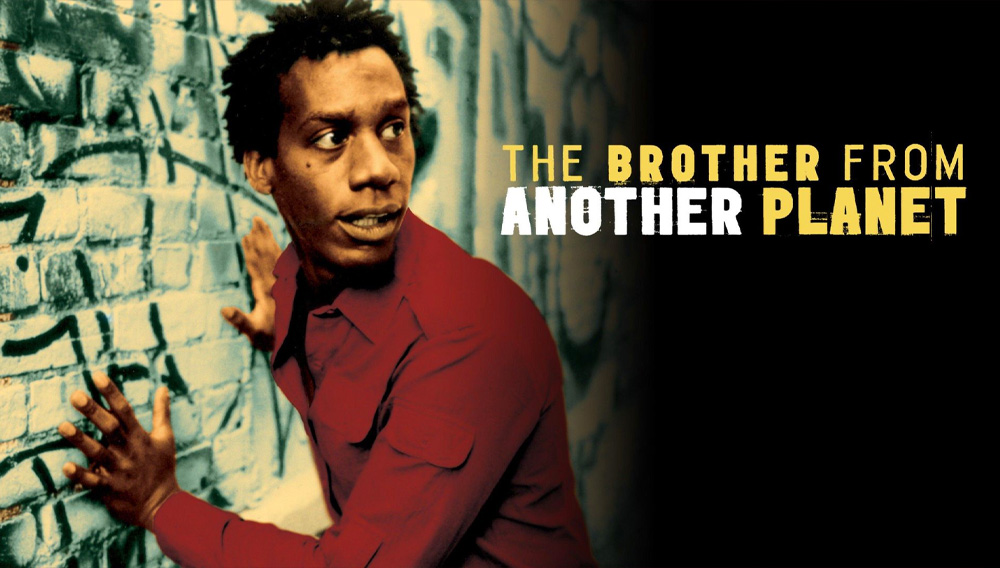

The story tracks the adventures of the titular Brother (Joe Morton, in an expressively wordless performance), a mute empath who rockets to Earth in tattered rags and a pair of M.C. Hammer-ready parachute pants, traversing Manhattan in a search to find more beings like him, meanwhile providing a blank slate for every stranger he meets (and often befriends) to project themselves onto. Much of the actions roots around Harlem, and the inviting dive bar where the Brother stumbles into something like community and understanding, but also pivots across the city, registering the observant and sometimes perplexed views of the ultimate tourist—who, just like millions of others, has come to the Big Apple from far away, looking to find his destiny.

The film falls perfectly into the cycle of mid-1980s indies set in a New York City steering its way from the tenement funk of the ’70s to the apparent flash and affluence of the Reagan Era, situating characters within the tension of that cultural shift. The uneasy new world into which our wordless hero arrives also is recognizable in the street scenes, and the often-urban soundtracks (polyrhythms meet postpunk), of Smithereens (1982), Stranger Than Paradise (1984), After Hours and Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), She’s Gotta Have It—which shared cinematographer Ernest Dickerson—and Something Wild (1986). Even more so, the narrative offers a nearly uncanny parallel to one of 1984’s biggest box office successes, James Cameron and Gale Ann Hurd’s The Terminator (which owes more direct debt to a classic source, Chris Marker’s La Jetee). Rather than in Griffith Observatory, the Brother plops down at Ellis Island, as has many a poor immigrant before him, missing his right foot—amputation once was a punishment for enslaved people who ran away and were captured—which his assortment of unique superpowers allows him to regrow (with all three toes intact). And like resistance warrior-from-the-future John Connor, this refugee from oppression is pursued by a relentless nemesis. In absurdist contrast to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s iconic man-machine, these space-cops are a pair of clueless men-in-black (played by writer-director Sayles and David Strathairn), whose turtlenecks and dorky mannerisms anticipate the Nihilists in The Big Lebowski—more a joke than a threat, even if the threat keeps the Brother moving fast on his feet.

Morton (who ironically plays the inventor of the robot overlords Skynet in Terminator 2: Judgment Day) imbues the Brother with generosity and grace. If presented with a certain guileless innocence, he’s neither averse to carnal pleasures—as a meet-cute encounter turned one-night stand with jazz singer Dee Dee Bridgewater reveals—nor imposing some payback of his own, as he uses optic trickery (a detachable eyeball that doubles as a surveillance camera) to expose, and depose, the head of a drug ring. This was Sayles’ fourth film, a box office rebound after the New Jersey period romance Baby It’s You that was made in the wake of his MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant. While critics at the time dinged it for having clunky storytelling, a lot of the film’s jesting vibe and episodic sequences bounce with a scruffy charm. The extraterrestrial humor is wisely generated out of the Brother’s own sense of character. In one running bit, his healing touch applies not only to the regeneration of appendages but to the shorted-out electronic guts of video games, especially the ones (very popular at the time) bleeping, blorping and frippering away with simulations of intergalactic warfare. Both funny and tragic is the antagonized regard the Brother has towards the police. Even when one of the cops tries to be friendly, he bails out of the scene quickly. ACAB, he seems to think, regardless of his open acceptance towards our planet.