At 92, Sonny Rollins hasn’t performed in a decade. His farewell concert was in 2012, and pulmonary fibrosis caused him to set his mighty horn aside two years later, but he remains the greatest living improviser in jazz. The lean, leonine tenor saxophonist, nicknamed “Newk” for his resemblance to Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe, is among the last figures who emerged from the music’s tumultuous 1950s to now walk the earth. This feels right, as he is arguably also the ultimate jazz soloist. Evidence abounds on countless recordings, many of which listeners can find these days in minty audiophile vinyl reissues and box sets. There’s also Aidan Levy’s massive 2022 biography “Saxophone Colossus” (Hachette Books), which at 772 pages makes room for an astonishment of micro-details, particularly vivid in its account of gigging on the road as a Black man in segregated mid-century America.

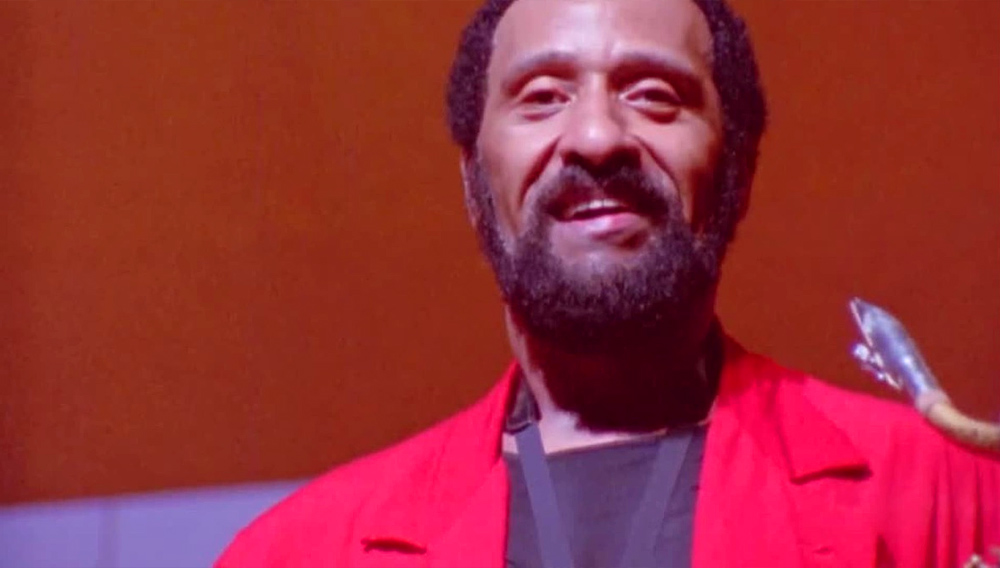

SAXOPHONE COLOSSUS Trailer from filmmaker Robert Mugge.

All of which is to say that there’s probably no better time to start digging Sonny Rollins. Even in the great man’s twilight, he’s ever-present. The 1986 documentary Saxophone Colossus, now streaming on Fandor in their “No Wristband Required” collection, makes an easy introduction to the artist in his mid-50s, with concert performances in upstate New York and Japan, plus a conversation between filmmaker Robert Mugge, Rollins and his wife Lucille in Central Park. The film also introduces a trio of jazz critics (Ira Gitler, Francis Davis and former Village Voice stalwart Gary Giddins), who wrangle with the saxophonist’s accomplishments and appeal. Davis suggests that while Rollins’ cultural influence is exceeded by the game-changing innovations of Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Ornette Coleman—”unlike them, he never formed a band in his own image”—he nonetheless represents “the most excellent standard of jazz you can possibly imagine.” Giddins, meanwhile, pays respect to the musician’s spellbinding improvisatory gifts and the “Aristotelian perfection” of his solos. “He manages to sustain interest for 10-12 minutes in a way that very few improvisers have been able to do.”

Mugge has directed more than 30 documentaries*, most of them music-oriented, including the much-loved The Gospel According to Al Green (1984), Sun Ra: A Joyful Noise (1980) and the juke joint road trip Deep Blues (1992), in which the late New York Times critic Robert Palmer helped to bring wider attention to the raw, Mississippi hill country sound of R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough. Mugge’s relaxed, no-fuss style favors extended concert clips and plain conversation to more contemporary frills of the rock doc, which lean on fancy editing of archival footage, jumpy and truncated musical segments, and can feel too closely aligned with brand marketing.

Saxophone Colossus touches on the best-known Rollins anecdote, his routine practice sessions on the Williamsburg Bridge between 1959 and 1961, during a brief retirement (at the grand old age of 28). The film also explores his love of calypso, with a generous and rousing performance of his show-stopping standard “Don’t Stop the Carnival”—a crowd-pleasing favorite replete with volleys of solos that pretty much justified the price of any ticket to his shows. It’s paired with footage from a collaboration with the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra, presenting “Concerto for Tenor Saxophone and Orchestra,” an unusual setting for Rollins that takes him outside of the familiar trappings of his group. But even the more conventional set (staged at a rock quarry in Saugerties, NY’s Opus 40 sculpture park), has its surprises. In the middle of playing, Rollins jumps off the stage and takes a bruising landing, breaking his heel but not his musical stride. (Maybe he has more in common with that other Rollins—former Black Flag frontman Henry—than we ever thought).

If you wonder how it might have come to that, listen to Rollins on his thinking about solos. He’s trying to “blot out my mind as much as possible and just let it flow by itself…” Go on, King.

* Now on Fandor, more music docs from director Robert Mugge: Black Wax (1982, also part of “No Wristband Required”), Hawaiian Rainbow (1987), Kumu Hula (1989), The Kingdom of Zydeco (1994), and Last of the Mississippi Jukes (2003).