On the short list of movies made about movies that were never made, Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno sits near the top. It’s a fascinating descent into the perilous rabbit hole of artistic madness, an object lesson in the dangers of an auteur gone wild. It’s not unique in this regard. There’s a broader category of documentaries that explore directorial excess on set, such as Eleanor Coppola’s Hearts of Darkness, a painfully revealing on-set diary of her husband’s troubled Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now. But that’s a now-classic film that everyone knows about and can handily quote its famous dialogue. No one in the wider moviegoing world ever saw a frame of what was to be Inferno.

The film was abandoned in 1964 after Clouzot had a heart attack on the set and insurers balked at going forward. Although the celebrated director of The Wages of Fear and Diabolique managed to complete one more film, 1968’s La Prisonnière, his ongoing health problems dogged much in the way of a sustained comeback. What if he had completed Inferno? Would it have been a masterpiece—or a glorious mess? We’ll never know. But film preservationist Serge Bromberg, working with Ruxandra Medrea, gives the world an extensive peek at what could have been in this “unmaking-of” doc, originally released in 2009 and now streaming as a Fandor Curator’s Pick.

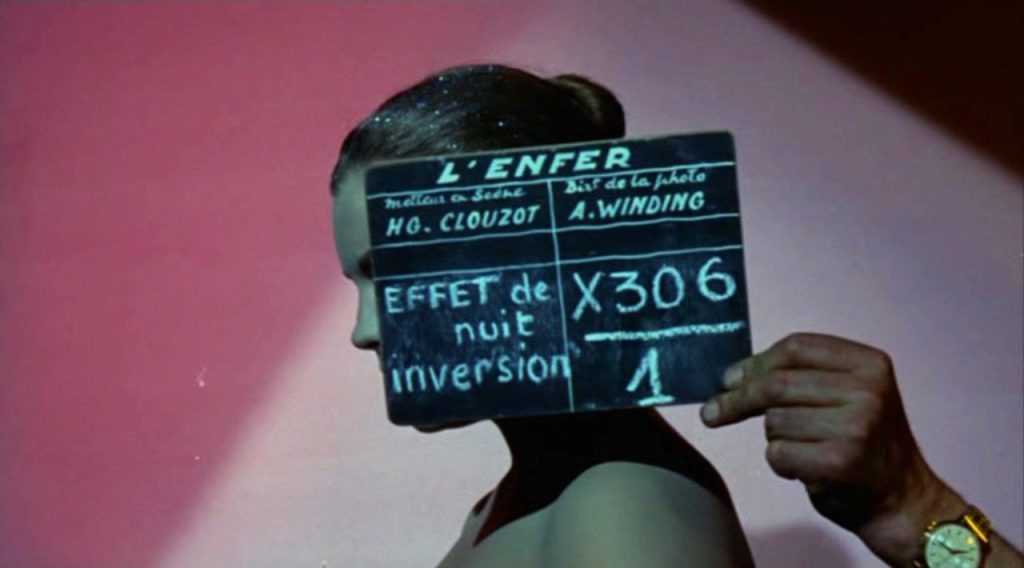

Drawing on some 15 hours of footage contained in 185 cans that he recovered—after meeting Clouzot’s widow in a stuck elevator—Bromberg rescues enough of the filmed scenario to sketch out the narrative. It’s a tale of jealousy between a middle-aged husband named Marcel (Serge Reggiani) and his beautiful young wife Odette (Romy Schneider, 26 and a rocketing star) in the French resort town where they run the hotel. The site was, in fact, Clouzot’s own beloved getaway from Paris, but the lakeside vista had a caveat: Engineers were poised to drain it for a hydroelectric project, which limited the production to a 20-day shoot.

And yet, that was the least of the film’s challenges. The leading man walked off after a week, complaining of “Maltese fever.” Clouzot, never known as an easy man to work with (he infamously once drugged Brigitte Bardot for a scene), only kept doubling down, having been handed a more-or-less blank check by Columbia Pictures.

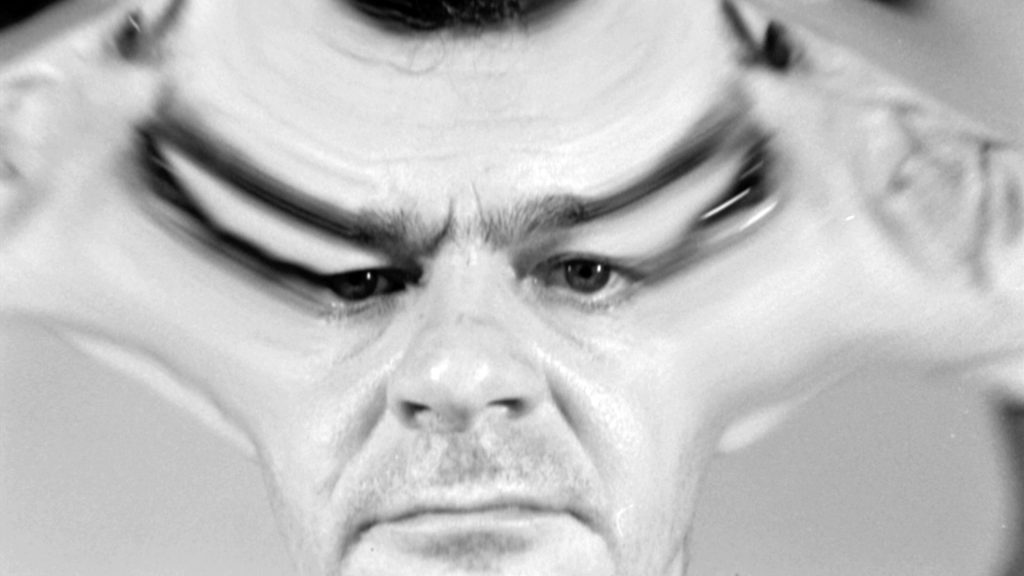

He had his reasons. Under siege from the young guns of the French New Wave and bewitched by the bold surrealist flair of Fellini’s 8 ½, Clouzot was keen to contemporize his new film and went all-in on the revolutionary cultural currents of the day. He looked to Pierre Boulez’s avant-garde IRCAM in Paris for an electronic soundtrack, and explored the use of kinetic art, devoting endless hours to test shoots that employed intensive visual effects. The disorienting passages were intended to represent the husband’s increasingly unstable mental condition as resentment eats him alive.

Much of the fun in Bromberg’s recasting of the tale lies in the extensive footage from these experiments. They’re shot in black-and-white and color—much as Clouzot imagined the finished film would be, erupting into the vivid tones of a dream (or nightmare) as Odette’s infidelities seize Marcel’s fantasies. The exercises offer a funhouse counterpoint to the anecdotes about the director’s controlling hand: His thorough and utterly precise storyboarding, his perhaps brutal treatment of actors to get a desired effect. The process may have been healthy for Clouzot if he wasn’t so obsessive, or if the process wasn’t so exhaustive.

The movie-about-the-movie also features a series of fill-in readings from the script, featuring Jacques Gamblin and The Artist‘s Bérénice Bejo, which convey some of the emotional tension that might have been, while an assortment of professionals who worked with Clouzot offer candid testimony. They include Costa-Gavras (Z), then a production assistant, and William Lubtchansky, then an assistant cinematographer, who would go on to shoot with Jacques Rivette, Jean-Luc Godard and Philippe Garrel.

Ultimately, not all was lost. Clouzot would incorporate some of the more fantastical, psychedelic elements from Inferno into the erotic psychological drama La Prisonnière. And this documentary stands as evidence of the director’s ambitious vision—unfulfilled, perhaps, but not for lack of trying.