When we think of movies, we always start with the visuals, which come straight at you, as film editor Walter Murch describes it. “You look at what’s in front of you, and it’s seen all at once, in a single grasp. Let’s call that the front door,” he says. But what of the soundtrack, which functions in more mysterious ways? “Sound tends to come in the back door, or sometimes even sneak in through the windows or through the floorboards,” he says. “And while you’re busy answering the front door, sound is sneaking in the back door.”

Murch’s theories on sound clearly resonate with the audio stylings of Leslie Shatz, a master of sound design, who was nominated for an Oscar for his work on 1999’s The Mummy. Art-house viewers are probably more familiar with Shatz’s work with Gus Van Sant (he’s worked on every film since Even Cowgirls Get the Blues), particularly the memorably expressionistic tracks in Gerry, Elephant, Last Days and Paranoid Park. But if you look around Shatz’s resume, he’s made other amazing contributions to film sound, whether for Todd Haynes’s I’m Not There and Mildred Pierce, Kelly Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy and Meek’s Cutoff, or most recently, Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave.

Shatz recently spoke to Keyframe about music concrète, technical unacceptability and the sounds of trains.

Keyframe: So what are you working on now?

Leslie Shatz: It’s a documentary called The Great Invisible about the Deepwater Horizon gulf oil spill off the coast of Mexico by Margaret Brown (The Order of Myths).

Keyframe: You really do it all: docs, short films, Hollywood movies, indie movies?

Shatz: Well, I got into this business because I love movies. The first movie I loved was Goldfinger; after I saw it, I thought I’m going to be a secret service agent like James Bond. Then my friend’s father took me to see Citizen Kane, and that was an eye-opener. That was the indie film for me, at the time. I saw it at a community center theater, it was in black and white, and it was so moving. And then I went from that to making my own documentary, one about the KKK in the early seventies (The New Klan: Heritage of Hate). It was great to come back to documentary with Margaret, and it once again renewed my love for documentaries. It also takes place in the South, like my first documentary did, and I love the foreignness of it: I love the sounds of the bugs and the twang of the accents. It takes me back to thinking I was in a foreign country. It was really the first foreign country I ever visited.

Keyframe: What about going back and forth between Hollywood and indie?

Shatz: I fell in working with Gus Van Sant, and he likes to think of me as an action guy, and Stephen Sommers, who directed The Mummy likes to think of me as the art-house guy. And I think Gus likes to think I bring a Hollywood film sensibility to his work, while Stephen likes to think that I bring an art-house sensibility to his. The one thing I don’t like to do is violent movies. Doing what I do, you have to watch a movie 100 times in post, and if you watch a movie with a 100 murders, that’s a lot of violence.

Keyframe: Can you talk about music concrète? What is it and how has it influenced you?

Shatz: As I understand it, it’s music with real concrete sounds. I remember one composition by Pierre Henry called something like composition for a barn door and scythe, and he went all over the south of France to find a barn door with the right squeak to it, and he played with all kinds of rhythms and punctuations. It was typical of the sixties and seventies, and I don’t know if it would really hold up now. But a mentor of mine introduced me to it. I thought it was wacky, and I tried to do it on my own. When I did sound for Catherine Leroy’s Ron Kovic documentary Last Patrol, she lead me into the middle of a riot outside of the Republican National Convention, when Nixon was going to be nominated for his second term. I recorded it and turned it into a music concrète composition. I tried to tell the story with the sound, use helicopters, tear gas, people screaming, it was pretty horrific…

I consider it to be about elegant choices and appropriate levels. I view sound in movies as being about the entire movie. People don’t watch a film in moments; they watch it from start to finish and the sound design should be the same. I’ve received a lot of positive remarks about 12 Years a Slave, and the sound takes place over the entire arc of the movie.

Keyframe: Most art-house filmgoers are probably most familiar with your work on Gus Van Sant’s more expressionistic movies from the 2000s. Can you talk about how you went that more stylized route with him?

Shatz: It really started with Good Will Hunting. The fight scene in the movie was where Gus said, ‘We have to go crazy.’ And I said, ‘What does that mean?’ In the scene, Ben [Affleck] beats the shit out of these guys, and it goes into slow motion, and when we looked at it, we started playing these sounds that are completely out of touch with what we’re seeing to touch on the mental chaos of the character. We put up like fifty different sounds on the consul: ‘Try this one here; try this one there,’ and that was maybe the beginning.

When we got to Gerry, Gus had just failed commercially with Psycho. And like a lot of directors in that position, he thought fuck it, I’m going to finance something minimally and he wanted to throw everything up in the air. Part of the idea was we started seeing the Dogma 95 films, and that really clicked. We wanted it to do it in the purest way possible. So we went to the desert and it was actually based on this Idiot’s Survival Guide, what do you do if you are lost in the desert? But this was all frustrating for me, because I’m a technician: it can’t be too loud or too soft, and there was a lot of wind noise. But he didn’t give a shit about that. I considered it unacceptable; I said, ‘People will think it’s amateurish,’ and he was like, ‘I don’t care.’ We tried looping [the dialogue], and then we realized it just stuck out. We tried folly. It didn’t work. Anything that seemed like an intrusion into the purity of the sound, the film rejected it. So we mainly used contrapuntal elements to the image and the sound that were there in the first place. Like on the long walk sequence, we put tones that didn’t belong there. I think Gus started to develop that style in his mind. He works so much from his instincts. Now people come to me and say, ‘I want a soundtrack like Elephant.’ But you have to have guts of steel to do that. The creative decisions he stuck by were so against the traditional standards. And they scared the hell out of me, too.

I remember when we played Elephant for HBO for the first time, they hated it for all these reasons: There was no background, there was no folly, and a lot of the sound made no sense. Sometimes, sound is coming out of the left where it should be out of the right. They declared it technically unacceptable. And that’s how they attacked the aesthetics of the movie. But I saw that was a problem with the standard methodology. People hide behind those technical aspects, because it keeps you on solid ground; if you stay within those, you’re safe. But that’s bullshit, because you don’t go anywhere. You’re only copying what came before you.

Keyframe: Whose idea was it to be use those tropical rainforest sounds during the shooting spree in Elephant?

Shatz: The way that we worked is the way I’m working more and more nowadays. It’s how I worked with Matteo Garrone on Gomorrah and I just did a commercial with Apple for iPhone, and it was the same. We sit together, we watch the thing, and we say, ‘let’s try this, let’s try that,’ and put up a palette of sounds, play it back and go to lunch, and tell stories, and the next day, it’s the same. They’re building blocks; it evolves; it’s a collaboration, I’m sure the good ideas are Gus’, but the process is interesting. Before the technology evolved, there was more of a formal distance between the director and the people doing the sound: The director would drop it off, and the sound guys would say: ‘We’ll call you when it’s done.’ Now it’s more spontaneous. Gus will come in with a record album. And then I’ll try something off of iTunes, or YouTube. It comes from everywhere, like found art, where whatever the artist finds has a relevance to being there at the right moment. Then once we have it all chosen, there’s a refining process, and then there’s a point where we stop refining. I usually want to keep refining. It’s my whole thing with technical acceptability. I’m still afraid a bit that HBO is going to come and say, this is technically unacceptable. But the good story about Elephant is that the Cannes screening committee watched it and loved it, and they said, ‘That mix is spectacular.’

Keyframe: You’ve also worked extensively with Todd Haynes and Kelly Reichardt. There’s a real Portland, Oregan posse there. How did you meet up with Reichardt? And can you talk about working on her films, which may not get as much credit as Van Sant’s, but the sound design on those films is just as expressive.

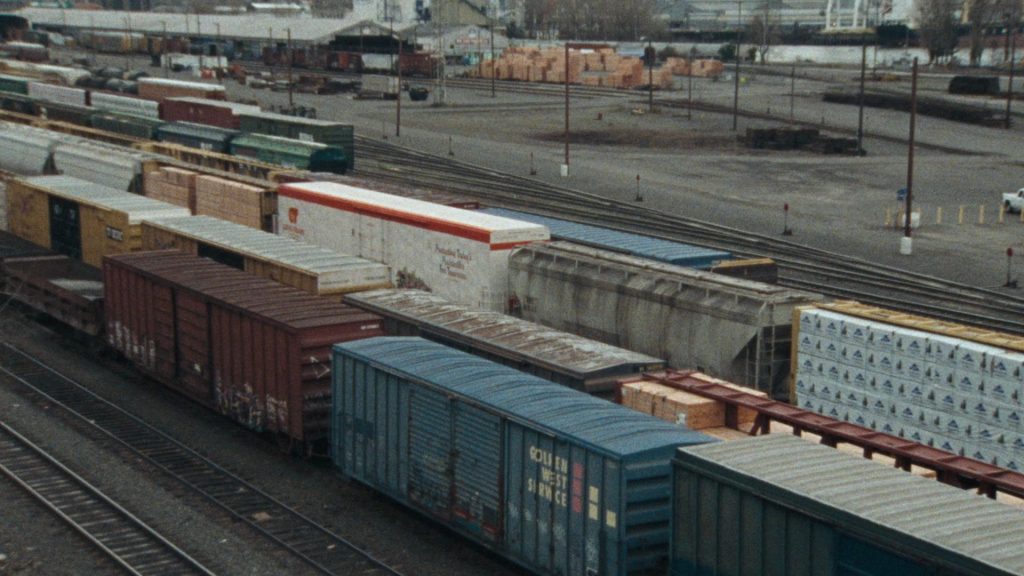

Shatz: I think it was through Todd. I wasn’t that familiar with her films, but I liked Old Joy. And Wendy and Lucy is a really subtle film. I love working with filmmakers like Kelly, because she’s not pretentious. She approaches it directly, and operates economically on a very low budget level. We worked the same way as the economic conditions of Michelle William’s character. I remember she brought in the film, and said, I want a soundtrack that doesn’t overwhelm: We have to make the dog pound sound scary, and she wanted to underline through the radio the bad economic indicators of our time, though I remember throwing some of that out. And the whole idea of the trains in the film was perfect. I had spent time on Paranoid Park recording trains in Portland. They’re a lot of trains going through there. Recording trains is an exercise in futility. Whenever you want a train there, forget about it. We were chasing trains all over town, but we managed to get some really great train sounds. And they have this aggressive nature. We would use five or six train sounds at any given moment: one with insistent horn, one with the approaching engine, all of that’s involved to make it sound great and scary. It was very appropriate because of the location: Every place has a certain character to it that’s subtle and unconscious and they were the right trains, because they had the right provenance.

Sound design doesn’t have to be some whiz kid with a synthesizer. Sound design is just choosing the right sounds and silences from the places. I did a seminar at Sundance and showed Jean-Pierre Melville’s The Red Circle and Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. And those films didn’t have giant sound crews; they just had a director who understood sound as a tool in their toolkit. Whatever we did with the forest on Wendy and Lucy, it was effective because of how it fit into the entirety of the scene.

Keyframe: Regarding the next film you did with Reichardt, Meek’s Cutoff, I had read that Sergio Leone’s Once Upon A Time in the West was a huge influence on you. It’s definitely apparent in Meek’s.

Shatz: I’m almost embarrassed about that. I actually worked with Sergio Leone on Once Upon a Time in America. But yes, the squeaking of the wheels was a motif in Meek’s, too. Kelly wanted to take all of the elements of music concrete and MS recording, which is a kind of spatial recording. We were able to create a really spatial feeling on the salt flats, which is particularly vivid when the wagons crash, because it really depicts the sound-space with the reverb and echoing from the hillside. When the final wagon comes to rest, it speaks of utter futility; the emptiness is all there.

Keyframe: Can you talk more about this MS recording. What is it, exactly?

Shatz: It’s a form of stereo, but it’s not right/left stereo. I had the idea on Elephant, which was the first time we used it. MS means mid-size, and the mic is recording directly in front and a microphone on the side, and when you combine the two, you’re able to create the spatial feeling of the environment. It worked really well on Elephant, in the school, and it worked really well in Milk with the crowds, and it really worked in Meek’s with that reverb. Once you became aware of it, you can see how it’s playing on your perceptions.

Keyframe: There is a really interesting device in Meek’s in some of the dialogue scenes where you barely hear the men speaking in the distance. Was it a challenge to try to get the levels just right where you can kind of make out a bit of what they’re saying, but not really?

Shatz: It was one of those technically unacceptable things. Kelly said, ‘I want you to be eavesdropping, so you only hear a little of it.’ But she was right: I love being proven wrong by directors. We want people to be leaning in and straining, because they’re engaged with the film. She also really liked the idea that men folk were doing the planning and Michelle’s character was always at a distance. It’s the use of the sound tool box to make a political statement, without being obvious about the women being kept in the dark. Maybe people observe that idea in a more subtle way.

Keyframe: Meek’s has lots of sounds of the wind on the plains, but I was also wondering how you use silence in your work. Can you have no sound?

Shatz: Silence is the scariest of all. It really has to come from the director. We’re paid to put stuff in, you know? I can’t say I have this great concept: ‘nothing.’ Then it’s like: ‘What are you paying me for?’ True silence is hard for audiences to take. That may be the next frontier: true silence, punctuated by some sound. Even in 12 Years, which has a lot of quiet in it, there was always a bit of sound. If you go into a movie theater, and there’s no sound, people think there’s something wrong, but that’s not necessarily bad, because you want to move people. You just have to move people in the right way.