If “Cult Movie Bingo” existed, Chameleon Street would check an inordinate amount of boxes, while still remaining an enigmatic one-off. It is the debut (and only) film by a brilliant writer/director, who was unappreciated in his own time, and a hidden gem in the undervalued area of African-American cinema. Funded mostly by the director’s friends and family, the film comprises inventive sets, fantasy sequences, philosophical diatribes, and a charismatic leading man who seldom removes his trademark headphones. More than that, the movie serves as brilliant commentary of the systems it satirizes, a commentary, sadly, reflected in the film’s virtual relegation from the mainstream.

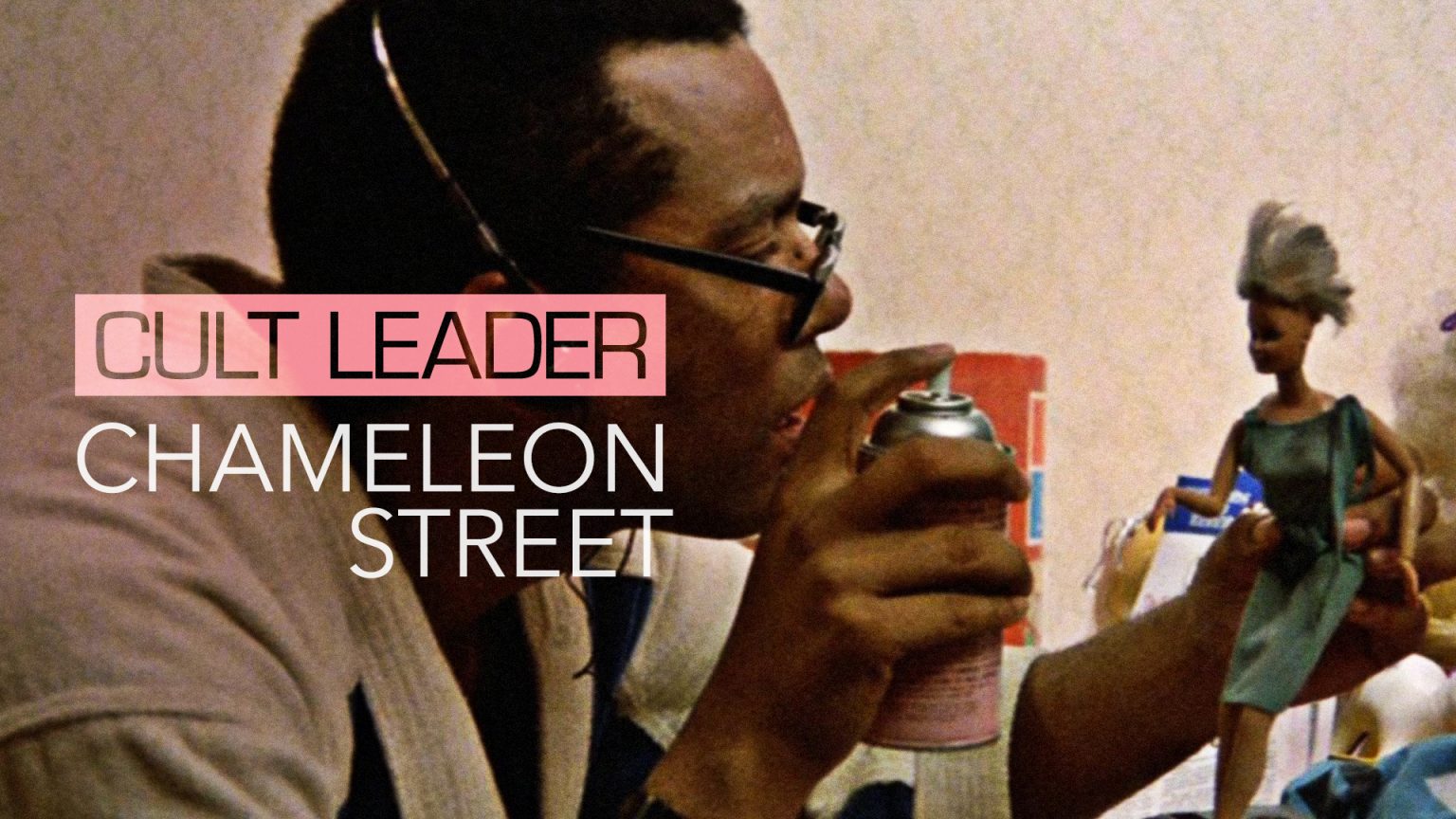

Chameleon Street, based loosely on real life con man, William Douglas Street, Jr., follows the the exploits of Douglas Street, Jr. (played by the film’s dexterous writer/director, Wendell B. Harris, Jr.) throughout the late 1970s and 80s. After incessant requests from his wife Gabrielle to “make some money,” Street begins his life of crime. He aims big, first attempting to extort money from the Detroit Tigers’ Willie Horton, before impersonating a journalist for Time Magazine, and then finally landing a position as a surgical intern at a hospital, where he frequently slips into the bathroom to reference medical texts when he cannot bluff his way out of the morning rounds. After a routine background check, Street is imprisoned for performing a (successful) hysterectomy. But when he escapes from prison he returns to his con man stylings, hiding out at nearby Yale University and impersonating an exchange student from Martinique. He goes as far as studying the speech patterns of Edith Piaf to become “Pépé le Mofo” (a play on Pépé le Moko, a 1937 film that follows a gangster of the same name who goes on the lam). His final impersonation, that of a burgeoning lawyer, ends only when his wife rats him out—perhaps a reference to another beloved French film, Godard’s Breathless.

Though undoubtedly due to the small budget (and to sharing a cinematographer with Michael Moore’s Roger & Me, which was filming concurrently), the flat lighting and Brechtian sets provide a docudrama effect, which compliments the film’s outlandish source material. These elements were readily accepted and praised within the works of contemporaries, such as Derek Jarman and Hal Hartley, and yet Harris was criticized for “lacking directorial prowess.” Harris was even a year ahead of Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami in his choice of recreating the circumstances around an infamous con man. In fact, Chameleon Street and Kiarostami’s Close-up would make for a very meta double feature.

Just as Kiarostami understood that cinema was a form of deception, Harris understood that life is a stage and all the players wear masks of some kind. The motif of masks runs through Chameleon Street, most memorably at a baroque masquerade ball where Street bypasses a Venetian mask for a darker variation of Cocteau’s plush Beauty and the Beast costume (another nod to French cinema). Masks are not merely used as a conspicuous allusion to identity; they are also possible callbacks to the notable appearances of masks in two other classics of Black Cinema—Ousmane Sembène’s Black Girl and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep.

Although Chameleon Street won the Grand Jury Prize at the 1990 Sundance Film Festival, it received no distribution deal. Warner Brothers bought the rights and an attempt at a remake went through several iterations with Arsenio Hall, Sinbad, and Wesley Snipes variously attached to the project. At one point Will Smith was the frontrunner to play Street, but no subsequent film was ever made (though it is worth noting that Smith played a suspiciously similar con man in Six Degrees of Separation just a few years later). As an actor, Harris’s only other credit of note was in Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (Soderbergh served on the jury at Sundance the year Chameleon Street won the Grand Jury prize). As a writer/director, Harris became stuck in “Development Hell” on a number of subsequent projects and never made another film, and audiences missed out on more urbane satire from a once-in-a-generation voice.

More 18th-century raconteur than Reagan Era criminal, Douglas Street Jr. is one of the most fully-realized characters in American cinema, let alone African-American cinema. The episodic structure and voiceover narration weave a picaresque story, which harkens back to classic literary characters like Don Quixote and Tom Jones. Street is Candide with a Walkman. Even the title sounds more like a road than a name. The street was both defined, confined and rescued by the malleability of his identity. He claimed to be able to size up a person in two minutes and become what they needed him to be. Despite the film’s refrain of “make some money,” he chose to dupe institutions rather than individuals and, in doing so, the film asks what it takes to make it in America if you’re a person of color. Harris, like Street, is a clever poly-hyphenate who tried to create luck where there was none, whose genius was suppressed by an institution that would not (and still does not) recognize him.