[Editor’s note: What kind of information can a close look at the 1985 Festival de Cannes offer us? A correspondent decided to take a dive into the competition lineup for this particular year to see if lessons could be learned or whether history is simply stuck on ‘repeat’.]

In a special to the New York Times on May 9, 1985, Hollywood correspondent Aljean Harmetz suggested what was perhaps obvious to anyone who glanced at that ’85 Cannes line-up: “The 38th Cannes International Film Festival opened tonight with a strong American flavor that will only get more pungent during the next 12 days.” While the biggest European star in front of or behind the lens was Jean-Luc Godard, many American stars flocked to the festival, including Harrison Ford, James Stewart and Clint Eastwood. In 1985, twelve of the twenty films in the official competition were in English—it was a year that featured no films from Africa, none from the Soviet Union and just one film from Japan. By most all accounts, the 1985 Cannes official competition was regarded as weak. According to Stanley Meiser of the LA Times, a film critic of the French newspaper Le Monde wrote that “the jury, if it really wanted to keep up the tradition of the Golden Palm, would award it to no movie this year.”

Long before the 1985 edition of the festival, Cannes had become a barometer of the cinema industry’s health, both financially and artistically. The success of the market has increasingly relied on the monetary power of America, which remains as of 2014 the top buyer during the festival. If the market is a judge of financial wealth and influence in the world of cinema, it is the festival’s official competition that should be the gauge of its artistic health. Its ability to showcase a diverse group of filmmakers from a variety of established and emerging nations has become key in measuring the festival’s success.

The 2015 edition has come under similar scrutiny as 1985’s for its lack of geographic diversity in particular, but in the present case, it has been accused of catering a bit too much to French films (as six out of the nineteen films in competition are “visibly” French—though at least three additional films were produced in part with French money). While cultural critics such as Jean-Michel Frodon see this as a potential threat to Cannes’ supremacy as the most important world film festival, ultimately the French cinema focus is not seen as as much of a problem as Hollywood itself. The biggest worry with the 2015 festival is that in catering so much to French filmmakers, it leaves the rest of the world shopping elsewhere for a showcase. And yet, while in recent years Cannes has premiered some questionable blockbusters, arthouse films still (of course) reign and diversity remains an important pillar in the festival’s foundational influence.

The heavy American presence in 1985 came about via a combination of factors, including the need for securing American money and the rising struggles of the European industry (just one example is Italy, which saw a drop from 631 million tickets sales to around 240 million between the mid 1960s and early 1980s). It wasn’t rocket science, as Cannes President Pierre Viot said, the glamour of American movies ”means more visitors and more journalists.”

Not everyone enjoyed the new direction of the festival, which was now focused on drawing more stars and more money. James Stewart, awarded a prize for a lifetime contribution to film in 1985 was asked his thoughts on the current state of the industry, and said “I think they’re substituting action which doesn’t have enough reference to the story. The movies are a visual medium, and I must say that I am getting a little tired of automobiles running off cliffs and running into a tree and then exploding. It’s as if the whole cinema industry is being taken over by the special-effects department.”

Spectacles of various kinds had begun to take over the industry—and this, undeniably, was tied to the power of the American cinema.

Coca-Cola and Americana: The Coca-Cola Kid, Pale Rider, Détective and Insignificance

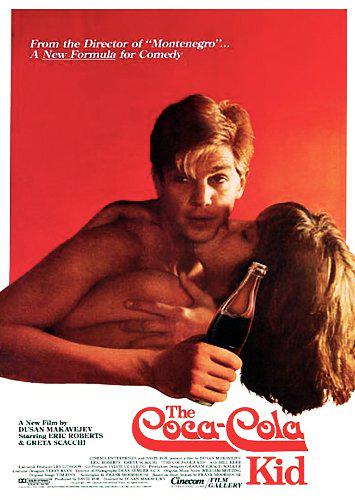

Just one month before the beginning of the festival in April 1985, Coca-Cola launched New Coke, which would only last three months before the classic formula would be restored. Yet, years after the public had rejected New Coke, it would continue to consistently beat both Classic Coca-Cola and Pepsi in taste tests. If it wasn’t an issue of taste, what was it? Coca-Cola was the subject of The Coca-Cola Kid, an Australian film starring an American actor, about an American company directed by Dusan Makavejev, a Yugoslavian director. As Becker, Eric Roberts gives a dazzling performance—Becker is a “fixer,” sent to increase sales in a valley area of Australia where not a single Coca-Cola has been sold. The reason? An old man is operating his own soft drink plant out of the valley and has completely saturated the market. As Becker searches for a solution, he finds love and is faced with some unexpected obstacles.

It should be telling that in spite of an opening title card making it clear that Coca-Cola had nothing to do with the production in any way, shape or form, that the company felt no need to pursue charges or even publicly condemn the film. The satire is muddled and unfocused—hardly scathing. In fact, with the red and white Coca-Cola banner hanging in about half the film’s shots, the film works more as an advertisement than it does a criticism of the company and what it represents. It is a strong contender for the worst of the American-style output of the 1985 lineup.

While significantly more worthwhile, Birdy (Alan Parker) and Mask (Peter Bogdanovich) fit into a similar category as The Coca-Cola Kid. They are both films that rely heavily on maintaining the status quo rather than challenging it. They are both films that feature strong performances and sensitive filmmaking, but do little to uphold or push the world of cinema in new directions or to new heights. It is likely that this group of films contributed greatly to the perception of the year 1985’s festival as pandering to Americans.

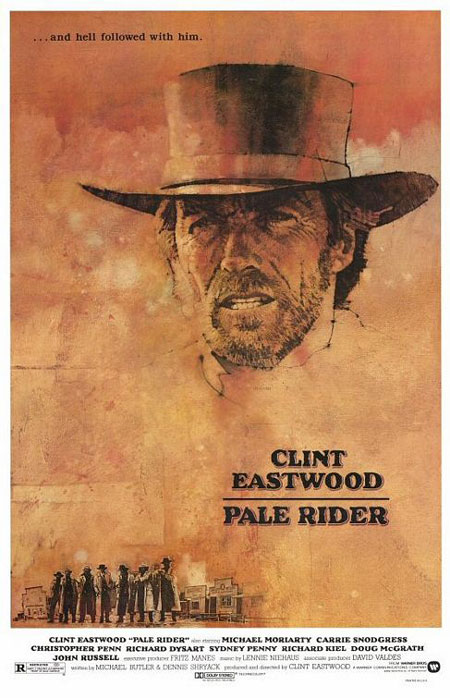

On the other hand, Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider managed to be a standout at the Festival. Pale Rider is about a mysterious preacher riding into town where he helps a group of poor miners rise up against injustice and greed. It is a deceptively simple narrative that allows grand formal gestures to dominate. The sprawling landscapes and dark, warmly lit interiors create a powerful contrast that really hearken back to a place lost by time. Each shot is immaculately framed, position characters in power struggles with each other, as well as with nature. The film’s only misstep, a misguided romantic subplot, does little to soften the film’s impact. The film expresses simply and poetically the values of hard work, supporting your family and equality—they resonate deeply under Eastwood’s careful eye. In an interview earlier that year with some young cinephiles with a camera, Clint Eastwood said of his own preferences “I may feel closer to a tradition gone by than a tradition today.”

While Eastwood’s homage to genre is done with reverence, Godard’s homage to Americana, Détective, is radical and unconventional. It is a reluctant tribute to the style and conventions of American cinema, in spite of fighting so violently against its symbolic power. No one makes cinema like Godard, who summarily demonstrates that it is impossible to create art in a bubble. His work here is meta-textual, with narratives within narratives, self-aware actors and disruptive musical cues. Yet, there is still reverence for the American screen. Beneath the disruptive techniques, Godard employs character archetypes in such a way that he is able to nonetheless create a surprisingly tense and romantic film about the nature of genre. Though seemingly worlds apart, there is a connection to the minimalism of Clint Eastwood’s films in this regard. Godard would even go so far as dedicating the film to Eastwood, as well as two other American auteurs, John Cassavetes and Edgar G. Ulmer.

Perhaps of all the American films in the lineup, none embrace Americana or spectacle as scathingly as Nicolas Roeg’s Insignificance. Based on a stage play of the same name, the film is about the meeting of four “fictional” characters who could not be more obviously based on Marilyn Monroe, Albert Einstein, Joe DiMaggio and Senator Joseph McCarthy. The film imagines an encounter between the four in the same hotel on a hot night in 1954. Playing with time, space and perception, the film eviscerates the romance of the 1950s. A meditation on fame and identity, the film is not only among the best the festival has to offer but also among the best works in Roeg’s illustrious career.

The fragmented and Möbius strip-like path of the film’s narrative and editing structure reveal the ultimate contradiction of the film’s title—insignificance is a matter of perspective, rather than a reflection of a scientific world where everything is, well, relative. The trials and tribulations of the film reveals a series of damaged personas who are caught between expectation and desire. This all leads to a fantastic, horrifying and explosive anti-climax that seems to bring to life the warnings and paranoia of Ronald Reagan’s second inaugural address in January 1985, when he brought up on multiple occasions the possibility of nuclear annihilation. As he offers his own desire to find a peaceful solution he evoked a terrifying reality: “Is there either logic or morality in believing that if one side threatens to kill tens of millions of our people, our only recourse is to threaten killing tens of millions of theirs?” This weight of impending doom hangs over Insignificance at the time, lending its frivolity and broad comedy a biting edge.

There were other English language or American “bred” films in that year, including Paul Schrader’s masterpiece Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters. The film itself defies most concepts of national cinema, and frankly stands above the rest of the output. A fictionalized account of author Yukio Mishima’s life, the film is a stylized tour de force which has only grown in prominence over the decades. It is very much a defining film of the 1985 lineup. There was the Australian film, Bliss (Ray Lawrence), which certainly did not earn the scorn that led to 400 of the 2,000-member audience to walk out. Then there is Joshua Then and Now, a Canadian film adaptation of Mortdecai Richler which has the Canadian television production values. Though watchable, it rarely transcends being “nice”—it’s ultimately harmless and forgettable. It is certainly a far cry from Ted Kotcheff’s 1971 Wake in Fright, a dark, dirty and horrifying examination of masculinity set in the Australian outback.

The Real Winners

Yet, for the weight of the American presence at the 1985 film festival, the biggest winners were far removed from the glamour of Hollywood. Arguably the biggest successes coming out of the festival were The Official Story, Kiss of the Spider Woman and the Palme D’Or winner When Father was Away on Business. While films like Insignificance, Birdy and Mishima would win some big prizes at Cannes, they would get little to no recognition beyond the festival.

While Kiss of the Spider Woman had the most American influence, it stars William Hurt and was shot in English despite being set in Brazil. Flawed as it may be as a political work (it’s far into the film that it becomes evident the film is set in Brazil and for the uninformed the conflict itself is never spelled out) it nonetheless tackles issues related to oppression, revolution and homosexuality that were radical given the era. Kiss of the Spider Woman would be nominated for four Academy Awards and William Hurt would win for Best Actor.

The Official Story, from Argentina, is easily among the very best films in the entire lineup. It is about a mother faced with a decision that puts the happiness and health of her daughter in the crosshairs. Visually it is quite straightforward but effectively uses the motif of fragmentation whether through mirrors or other reflective surfaces to suggest the way a wealthy bourgeoisie ignored the cruelty of the oppressive regime. The film would pick up a dozen or so awards and nominations in 1985, as well as winning the award for the Best Foreign Language Film at the Oscars.

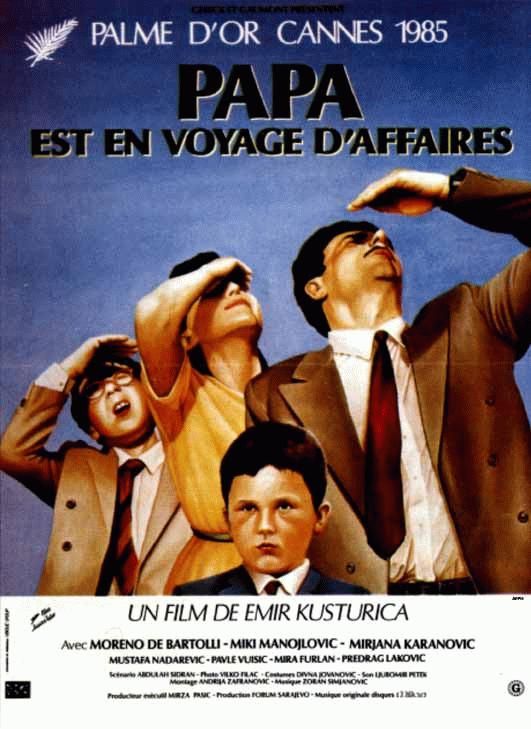

When Father Was Away on Business did not find nearly as much success as the previous two beyond its Cannes wins, but did well for itself considering it was from an unknown filmmaker (at the time) and from a country not particularly well known for it’s cinema. Perhaps, most importantly, it would set the stage for Emir Kusturica’s future success. Compared to the other films about oppression that would win big, Kusturica has a decidedly lighthearted and satirical approach to his subject. The film is warm, personal and loaded with clever and brash innuendo. While “charming” can often be used dismissively, it is the best word to describe Kusturica’s enterprise.

It is, indeed—despite the attempts to draw in and placate American tourists, journalists and money—difficult to question the integrity of a festival that awarded its top prize to such a small and vibrant underdog. The following year even bigger stars would be invited, including Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Barbara Hershey and Whoopi Goldberg—and none of them would end up attending due to the American bombings in Libya and the recent terrorist attacks on European soil (the French media seemed to take great pleasure in mocking those who skipped the festival, so at least cynical journalists were able to enjoy the festival.)

The 2015 edition of Cannes similarly adopts a political edge, though not for the same reasons. The lineup has been described as more political than romantic by Thierry Fremaux, the delegate general director of the Cannes film Festival, which he linked to the attacks on the Charlie Hebdo headquarters earlier this year. In his interview with Variety, Fremaux discusses how the attacks have forced a nation to reflect on its identity as he asks “How do we live together?” While perhaps that is not the right question, or at the very least it is just one of many, it will be interesting to see how politics will be reflected in at the final awards. While quality is meant to reign, it will be difficult to escape the political weight of films like Dheepan (Jacques Audiard) about a Tamil fighter fleeing Sri Lanka to find asylum in Paris only to find more violence. It will likely be seen as a statement, one way or another, if the festival awards its final prize to a perceived flight of fancy like Matteo Garrone’s The Tale of Tales over something perceived as more politically heavy. At the very least it shows that art does not exist in a bubble. It never has.