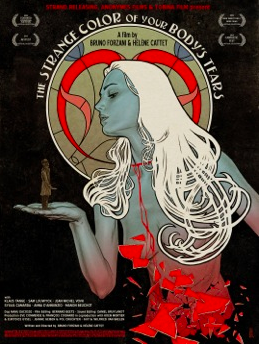

Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani have been quietly making their personal visions into vivid realities in Belgium for almost fifteen years. They began with short films (Catharsis and Chambre jaune) but it was their 2009 debut feature Amer that broke through, not only astonishing the world-premiere audience at the 15th Lund International Fantastic Film Festival but also ending up on Quentin Tarantino’s 20 Best of the Year list. Their first decade of filmmaking used a very bold brush dipped deeply in the viscous ink of seventies Italian giallo films (think Dario Argento’s unseen phantoms—black-gloved, multicolored and backlit). But the entwined pair have now issued a crime film that moves even deeper into space and sound. For those ready to take the plunge, their latest, The Strange Color of Your Body’s Tears, is a sumptuous bath.

Shade Rupe: We’ve talked about Amer before. A lot of people were really dazzled by what you guys did. You’ve taken somewhat of a different approach with your new film. You aren’t completely following giallo. You’re now using other film elements and you’re now exploring more of a narrative. You guys continue to play inside a universe of your own creation. The first word we heard was you would be making a similar film to Amer but with a male lead, but your film is actually quite different than Amer. What were some of the ideas you had when you began forming this film?

Bruno Forzani: In fact, we had written The Strange Color before Amer in 2002. We were still making Amer when we came back to The Strange Color and we realized that it was the same thematics about desire and fantasies but in a male character point of view this time. In fact, it wasn’t conscious. After having made Amer, we have discovered that it was the same thematically but with a different story to tell and a more maybe dark universe because we imagined that story in Brussels, which is more dark than the French Riviera with the sun and with the sea. It was these thematics of desire, sexuality and fantasies but from a male character’s perspective.

Rupe: You just mentioned the sun and the setting of Amer. Portions of the film happen outside. We see a chasing scene happening outside, the ball-playing is outside. Strange Color is not only more internal, happening inside an apartment, inside a building, but even inside there are strange holes in ceilings to another place. There are other dimensions inside. The idea of the film is actually much more internal than Amer.

Forzani: Yeah. Totally.

Rupe: The spaces and the shapes that populate Amer were definitely in that giallo zone but didn’t really happen in a specific place. In Strange Color we have these gorgeous Belgian buildings. Is that something we can see anywhere in Belgium or is that a special building that this was shot in?

Forzani: No. It’s a special building. We used seven houses to make one house. Many of the Brussels Art Nouveau houses have become offices inside and are very modern. It’s very difficult to find the original interior intact. We found one house in Brussels, the one with all the stairs, where you have all the floors, and it’s not open to the public. He’s kept it as a little jewel for him. Each path of the house is unique. The glass is not regular glass. It’s crystal and if you break it, it’s very expensive to replace. Each chair is unique. It’s a very, very precious location. We were only able to shoot inside this location because we are used to working with a small crew. There could never be more than ten people in the house, so it was okay for us, but for another movie with a big crew it would be impossible.

Rupe: Is there a history to the house itself? It’s incredibly unique.

Forzani: Yeah. The architect is called Victor Horta. He’s the main Art Nouveau architect in Belgium. He was like a revolutionary because he wanted to break all the rules of the architecture of this period with this house. In fact, the house is built on two houses and so there is, again, perspective, like an M.C. Escher design.

As it is built on two houses, you first have the impression of being in one house, and at one moment you have the stairs go farther than the previous stairs and it break all the rules of perspective. Because the stairs are in two houses, so you don’t understand the architecture very well when you enter the first time.

To understand this disorienting architecture, we spent three days inside the house to see all the possible shots we could do and to understand how it was built. It was perfect for the movie because we wanted a labyrinth design and this house was a real labyrinth. [We] put, inside this house, six other houses to [create] the whole house of the movie.

Rupe: What do you mean when you say it took six or seven houses to make up the one house?

Forzani: Yes.

Rupe: Were you aware that the house was built this way before filming?

Forzani: No. When we first entered, we were totally overwhelmed by the house. We were totally disoriented and so we told ourselves, if we have that sensation, that feeling, it’s better. It’s going to work for the labyrinth thing we want to do in the film.

Rupe: How much of your script was already written before you discovered the house?

Forzani: It was totally written and in fact it’s the storyboard that changed because when we had written the script, we had the images in our minds, a fake space that doesn’t exist, a fake house that only exists in our minds. When we have discovered this house, we used its architecture to do new storyboards, to create a new working space. The story was that same. It’s just at one moment that there was supposed to be an elevator but it couldn’t fit in this house, so we changed the sequence with the elevator. But all the other stuff is the same.

Rupe: The house actually dictated the film in some ways. The house also formed the film.

Forzani: The experience of visiting the house was so strong that we said to ourselves,’That’s the house because it has a big soul and a nice body.’ It will give all the soul to the movie, yes.

Rupe: It really feels like you and the house were working together and the house has such an organic feel to it. Its curves are at off angles. It doesn’t follow a symmetrical design. The window frame is stunningly singular. Does the house actually have a hole in the ceiling in that one room, or was that created? When she’s walking on the bed, was that an actual room in the house?

Forzani: No… well we don’t want to go too much into details, so as not kill the magic, but it’s not in the house, no.

Rupe: A very noticeable element of your feature films is the sound work. I feel very fortunate to have experienced your films theatrically. I am inside the universe of the film and I am hearing all of this heavy sighing all around me. It almost feels live. Yet, when I watched the online screener to make notes, it’s just coming out of my home speakers and it doesn’t take me away and into the film as well. Are you both working on the sound design? Are you a part of that also?

Forzani: Yes. We both are working on the sound. In fact, as in Amer, we didn’t make any direct sounds on the set, so we do it all in post-production with a foley guy and it’s like a second shooting. In fact, when we do the editing, it’s mute. It has no sound. When we have finished the editing, it was the film we had imagined but it hadn’t the strength that we imagined when we were reading the script. When we were reading the script, we had like a melancholia, a vertigo feeling after the reading. When we were watching the editing mute, we didn’t get that feeling.

When we begin to do the sound design after the editing, we have tried to get that back, that [feeling] we had during the writing and reading of the script. We wanted that the film would have a physical impact for the audience, and so we have worked a lot with the bass. With the bass, it’s really physical. Your body feels it and Helene got pregnant during this step of work. At one moment, she couldn’t come to work on some sequences because with the bass, it goes into the belly, into your guts and it’s very strong, and she had to leave for the baby. We have tried to work the sound to create a real physical impact for the audience and I think that physical impact, you can’t have it with your computer and as you say, with your little speaker. You can have it definitely in a theater. We have made the film for theater and maybe if you have a bigger home theater installation, maybe you can feel it.

In the theater you can really feel it. We have sound mixed for the film very high and very low because if the sound is not powerful enough, you don’t enter in the movie. You don’t enter in the trip, into the nightmare of the character and so it’s very important to have powerful sound to really experience it.

Rupe: You’re talking about vertigo and being inside of something. Is that staircase in the film part of the house also?

Forzani: Yeah, yeah, yeah. The staircase is part of this house.

Rupe: How old is that house?

Forzani: It was built at least a full century ago.

Rupe: Were you also production designers or did you bring in a production designer on the film?

Forzani: When we write a script, we also do all the scouting. In Belgium and in France, there is no production designer. It’s not a job. We work with a set decorator. We show all of our ideas and we discuss them, and the set decorator tries to complete them, to help us work out our vision.

Rupe: The whole film feels very Belgian. It feels very indigenous to the city itself. Did you have something in mind where you wanted to broadcast a Belgian atmosphere also or did that just happen just because you were shooting there?

Forzani: We live in Belgium, near the art nouveau houses. They are like the gates to the twilight zone. You come out of your real life and you go back a century before. It’s a way to go into a fantasy universe in Brussels, through this art nouveau. It really feels like that.

Rupe: Did you use any CGI in the creation of this film?

Forzani: No.

Rupe: How straightforward do you feel the story is and do you feel that it all comes across very clearly? I see the movie and I see it. Others just see a number of images and sounds strung together. How much of the film is this story and how much of it is purely experiential?

Forzani: Well, we had written the script about nine years before we started shooting. When we wrote the script, we tried to tell our story through cinematic sequences. We didn’t want to tell the story through dialogue and psychology. Dialogue will explain the character but we wanted the audience to feel the lust of the character, the madness of the character, and not know if you are in a dream or if you are in reality.

It’s written with the subconscious, like in dreams with a lot of images. We developed the film like this, the story like this and it’s a bit like a surrealistic way of writing. So for us it’s not an experimental movie. We have just tried to tell our story through cinematic language, images, colors, editing, lighting, sound and music, and actors too, and settings.

It’s like the choice of art nouveau. It’s viscerally linked to the storytelling with all the curves, with all these labyrinths. It’s not like we chose art nouveau because it was just the neighboring house from where we live. It was because it the way we wanted to represent women. In art nouveau, they are always presented like goddesses and we talk about sexual fantasies, so it was linked with that. It was linked with the character’s mind, with the story line, with all these curves. So it’s all very visceral, all very organic.

We spent nine years thinking about this movie. Each time we had the holidays off from our jobs, we were working on it. It was the first script we had ever written together. We have a very strong attachment to the film. It was a dream to do it and it has been a long time. It has taken a long time to achieve it. It’s not exactly like a baby but it has grown inside us for a long, long time. It was very visceral, organic.

Rupe: Well, a baby is nine months. Your film was nine years, similar.

Forzani: Yes, exactly.

Rupe: Are you already at work on your next movie or you’re more busy raising your living creature?

Forzani: The two, we are working on the two.