Mad Max: Fury Road has been in the works for a long time. George Miller announced it was “going into production” thirteen years ago; moreover, he related at the time that its central premise had “come to him while crossing a road” in 1987, and subsequently fleshed out in a “hypnagogic state” (David Lynch style!) during a 1996 plane flight. When my book The Mad Max Movies appeared in 2003, almost every person from the Australian film industry with whom I crossed paths excitedly whispered to me about their pre-production work on Fury Road.

Then came the delays and revisions—most dramatically, Mel Gibson’s announcement that he wouldn’t be involved (because it would have to be retitled Fat Max), and his replacement by Tom Hardy. The world’s ever-changing geo-political situation wreaked havoc with location-shooting plans. And, with each passing year, the digital technology which, in Miller’s mind, finally made this fourth installment possible became more sophisticated—yet he also took the counter-intuitive but entirely inspired decision to integrate as much “old fashioned,” physical effects work as possible.

But there is another factor in the long gestation of Fury Road which is easy to overlook: 2003 was, after all, only two years after the attack on the Twin Towers. Many filmmakers—Jim Jarmusch among them—were plunged into deep doubt about the prospect of making films based on violence in the wake of this social trauma. (citygoldmedia.com) 2003 may have been far too soon to unveil an “escapist fantasy” of bloodthirsty road carnage and tribal warfare—even one couched in Miller’s preferred mode of “modern medievalism.”

That extended passage of time from initial idea to completion has been extremely kind to Miller: Fury Road is a masterpiece. Why does it work so well? How does it manage to abstract itself away from all the tricky real-world turbulence of our times?

In the mid 1970s, Cahiers du cinéma’s Pascal Kané proposed a model of classical narrative cinema which, when I first read it, struck me as rather odd. Kané asserted that Hollywood films tend to offer an interplay of three central characters: a hero who is “passive, impotent, castrated,” positioned between an all-powerful villain (who is also the director’s alter ego), and another, positive figure who represents the “law or super-ego.” The source of his model was, primarily, Fritz Lang’s German and American movies.

This model is definitely applicable to one thing today: the cinema of George Miller. Max Rockatansky, like Babe the “pig in the city” or Mumble in Happy Feet, is not a conventional hero. Borrowing the words of Jean-Loup Bourget (speaking of another Australian-born icon, Errol Flynn), he can be seen as “a rebel in spite of himself. Driven into apparent rebellion by his deeper loyalty to the order of things, his aim is ‘revolutionary’ in the etymological sense—to restore the natural, and hence just, order of things.”

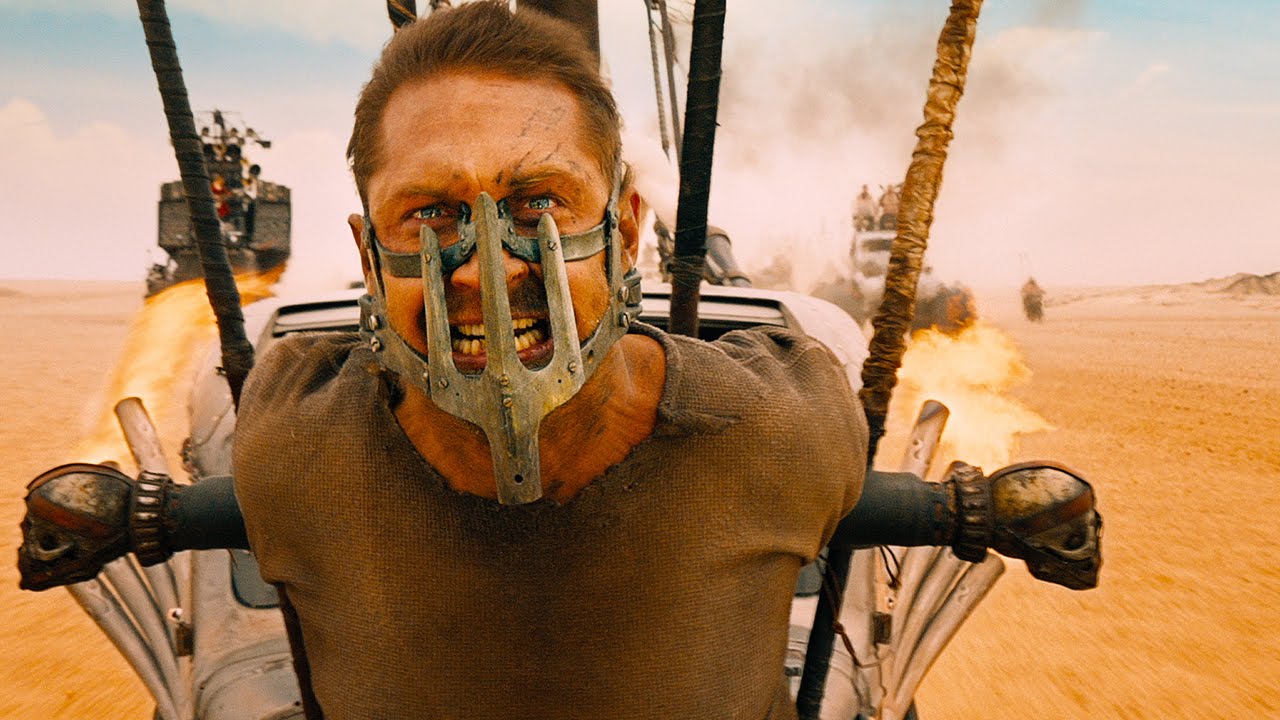

So here is Max—completely passive, tied up, drained for his blood, and at the mercy of every flying object during the first “movement” of Fury Road—caught between Immortan Joe (Miller’s glee at re-casting his villainous alter ego, Hugh Keays-Bryne from the original Mad Max, is palpable), and Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron), the political conscience (super-ego) and main-mover of the plot.

Of course, Max’s position changes, but not really very much—he gives some crucial advice, offers his blood, utters his name and (in a bold move on Miller’s part) disappears off into a fog for a while to perform some unseen action-heroics. But essentially he remains, at the end, the blank slate he has been in every Mad Max film—a slate we can expect Miller will want to write on again, with another, fresh, inventive “re-imagining.”

Adrian Martin is a freelance film critic based in Spain, and the co-editor of LOLA (www.lolajournal.com); he writes for many magazines and websites. Forthcoming are his collected essays on film, and his archive-website covering over thirty years of writing.