To analyze the portrait of any artist, one must embrace the grey areas — the imperfections, the weird, the obscure. In terms of photography, however, artistic value can be overshadowed by personal insecurities. When one expects to be photographed, appropriate smiles and spacing are essential. But when a subject doesn’t anticipate the camera’s circular gaze, or when the boundaries of acceptable behavior are crossed, artistry can be mistaken for an invasion of privacy. In the documentaries Finding Vivian Maier and The Woodmans, the filmmakers raise vital questions about artistic intent, and how the public often proclaims beauty after the fact.

In both films, the documentarians use the time to deconstruct the myth of two artists — to separate fact from fiction. During the 50s, a stoic nanny named Vivian Maier walked the streets of Chicago, unafraid of exploring the city’s lower depths with her Rolleiflex camera. Then, the other story shows the 70s through the eyes of an American teenager, Francesca Woodman, who developed her style via psychosexual self-portraits and abstract photography. Both women have been posthumously acclaimed for their work, and their unique personalities add to the mystique.

The Woodman’s director C. Scott Willis introduces Francesca via home footage, setting the tone for a parental commentary while acknowledging the subject’s ultimate fate. In contrast, Finding Vivian Maier’s directors — John Maloof and Charlie Siskel — take a less melodramatic approach, as they hold back on biographical information about Vivian while interviewing her many acquaintances to create subjective retellings of her life. Whereas Woodman’s story is mostly told chronologically, the Maier narrative shifts back and forth in time, thus raising more questions about her life story, rather than fully exploring the specifics behind her creative approach.

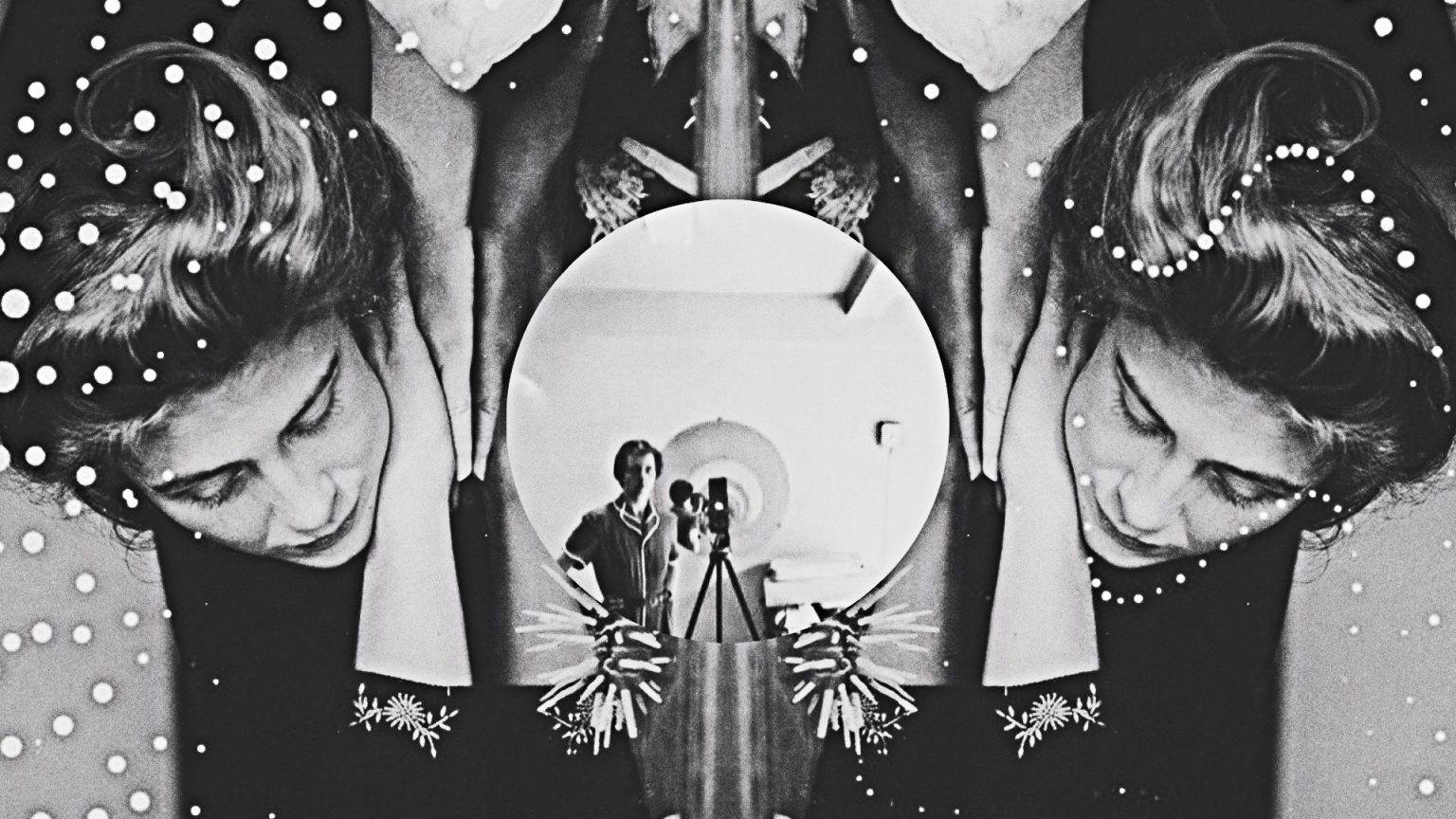

Because of Finding Vivian Maier’s unorthodox storytelling technique, the subject becomes a timeless figure, forever trapped in public perception — much like her photographic canon. Throughout the doc, Maier’s self-portraits reveal her personal style and stoic demeanor, yet she never seems to age — even as interviewees describe the final years of her life. By chronicling Maier’s relationships, or lack thereof, the filmmakers project a cinematic archetype: an antihero who wielded a camera to make people feel either submissive or sublime. For Maier, street photography represented a constant, a way to connect while also communicating a sense of societal detachment.

In photography, or even in film, a black and white frame can make people feel uncomfortable. During one of Finding Vivian Maier’s most fascinating moments, talk show host Phil Donahue describes hiring Maier (for nanny work) and not being impressed when she focused on the inside of a garbage can. “I didn’t think she was crazy,” he says — a telling comment about the distinction between practical and so-called “eccentric” personalities. It’s safe to say that Mr. Donahue found beauty after the fact.

Finding Vivian Maier features a peculiar woman, a woman who probably wasn’t the most ideal housemate, at least when living amongst married folk in America’s idealistic Midwest. But the end result of her life-long work reveals a woman who made the most of her freedom. Maier may indeed seem like a tragic figure for what she didn’t experience, but the fact remains that she lived to the age of 83; a crucial bit of information that mostly remains under the surface in Maloof’s documentary.

In the case of Francesca Woodman, her story parallels the creative journey of two artists that not only supported her evolution but also understood the struggle: her parents. Importantly, their perspectives drive The Woodmans’ narrative, resulting in a layered portrait of the subject’s bonds with men, women, and professional peers. If released in 2018, Woodman’s provocative self-portraits would probably be perceived as exhibitionism, at least to the average Instagram user, but — as her parents note in the documentary — nudity didn’t define the work, but rather complemented the totality of it.

Just as Maier’s primary occupation didn’t prevent her from being a legitimate artist, Francesca’s relative lack of life experience didn’t make her any less of a creative whirlwind. The former seemed to have difficulty maintaining friendships, while the latter struggled to balance personal happiness with professional proactivity. But the most important variable seems to be time and flexibility. Maier worked an honorable day job, all the while obsessively gathering mementos of her life experiences — both physical or psychological. For Woodman, her life ended just as her career seemed to be taking off. When artists pass, their virtues are perceived as quirks and eccentricities — convenient labels for the unimaginative to somehow make sense of it all.

Strange, weird, and obscure, people often used these words to describe things they don’t understand. All movies are fundamentally strange, but the final product is fun to watch (hopefully). Music is weird, but the end result brings people joy (usually). Any creative endeavor will seem obscure to someone, and many people will only lend their support after the fact (sadly). Vivian Maier and Francesca Woodman may have been strange, weird, and obscure, but they were also structured, committed, and driven by a creative fire that can’t be taught. To me, that’s beautiful.

Watch Now: The documentary, The Woodmans, here on Fandor.